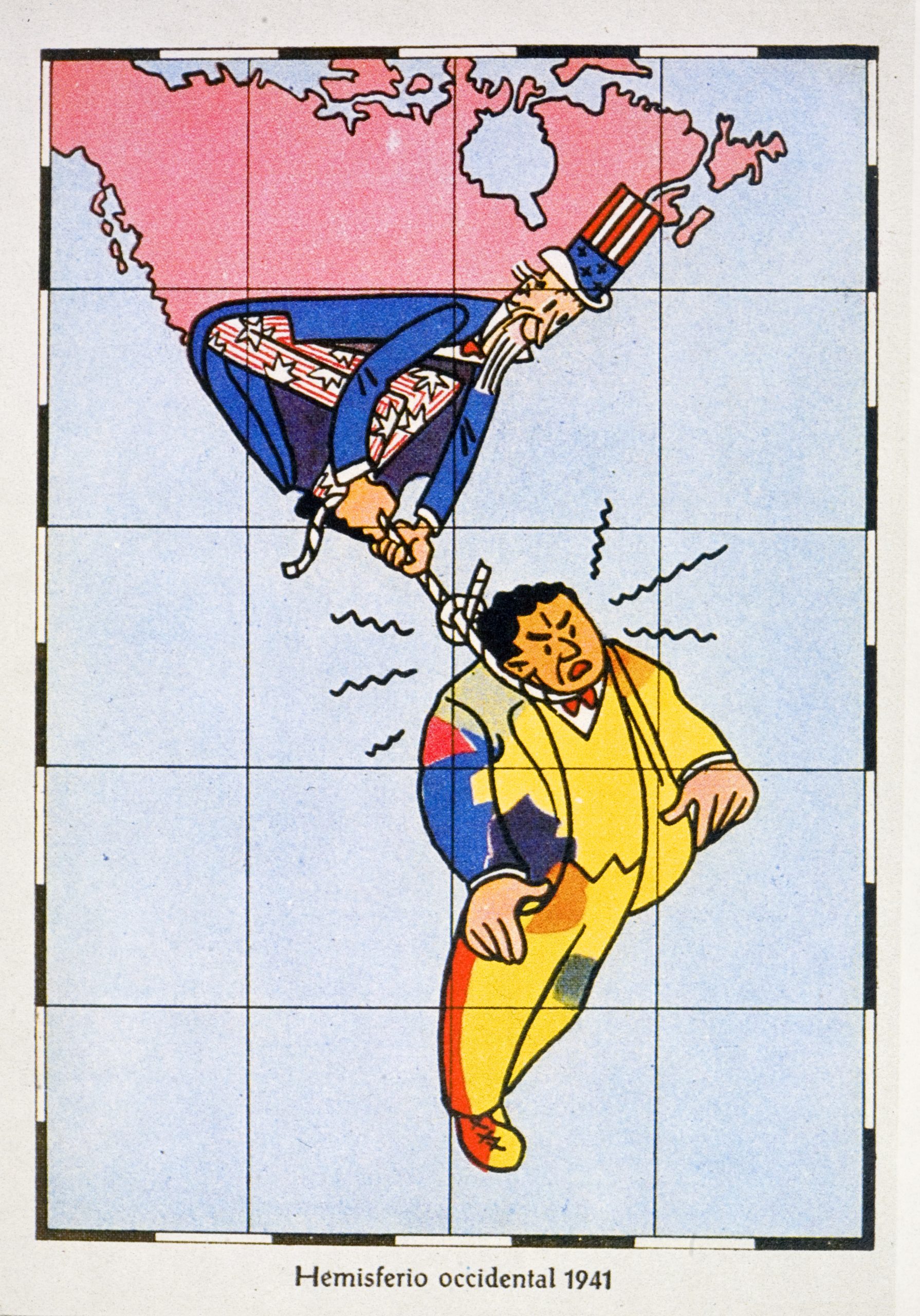

In December 1823, U.S. president James Monroe delivered his State of the Union address in which he coined what would become known as the Monroe Doctrine. It was a framework that would later be used to legitimize U.S. intervention up and down the hemisphere.

But in those early days, Monroe’s statements were applauded by Latin American leaders as supporting their independence struggles. They were even embraced at Simon Bolivar’s Panama Congress of 1826.

In this episode, host Michael Fox travels to see what’s left of the former site of the Panama Congress, and then dives in to the past and present with Yale historian Greg Grandin.

They look at Simon Bolivar’s Panama Congress, but also Monroe and the legacy of US imperialism in the region until today, including US-backed death squads, the Iran Contra Scandal, Manifest Destiny, and so much more.

Under the Shadow is an investigative narrative podcast series that walks back in time, telling the story of the past by visiting momentous places in the present.

In each episode, host Michael Fox takes us to a location where something historic happened—a landmark of revolutionary struggle or foreign intervention. Today, it might look like a random street corner, a church, a mall, a monument, or a museum. But every place he takes us was once the site of history-making events that shook countries, impacted lives, and left deep marks on the world.

Hosted by Latin America-based journalist Michael Fox.

This podcast is produced in partnership between The Real News Network and NACLA.

Additional info:

- You can see pictures of the Simon Bolivar monument, in Panama City, here.

- Follow and support Michael Fox and Under the Shadow at https://www.patreon.com/mfox

- You can follow historian Greg Grandin, on Twitter, here.

- Below are links to Greg Grandin’s books mentioned in the episode:

- The Blood of Guatemala: A History of Race and Nation (2000, Duke University Press Books)

- Empire’s Workshop: Latin America, the United States, and the Making of an Imperial Republic (Holt, 2006)

- The Last Colonial Massacre: Latin America in the Cold War (2011, The University of Chicago)

- Kissinger’s Shadow: The Long Reach of America’s Most Controversial Statesman (2016, MacMillan)

- You can find more of Greg’s books, here.

- Theme music by Monte Perdido, Deezer, Apple Music, YouTube, or wherever you listen to music.

- Other music from Blue Dot Sessions.

Transcript

Michael Fox: Hi folks, I’m your host, Michael Fox.

So, as you can see, I am still working on the final episode of Under the Shadow. But I have another exciting bonus episode for you today. And it begins here, in the heart of Panama City. I hope you like it.

So I’m in downtown Panama City, the old historic center. I’m in a plaza, and it’s a beautiful day. It’s now turned to the dry season, December, so there’s not a cloud in the sky. It’s just after sunrise, and, obviously, birds twittering everywhere. You’ve got eight or nine big trees with their roots that stretch into the ground. Nicely manicured little park.

It’s surrounded by little restaurants. There’s a coffee shop here, the Hotel Columbia is back here. It’s this big, orange adobe colored building. Some of the restaurants they’re setting up, because they’re setting up these big tables and things where people will sit out during the day here.

On one side is the National Theater, just across the street. Here’s the Palacio de Simon Bolivar, which is now used as the Ministry of Foreign Relations. And just beside that is this big church that’s about 150 years old.

The reason why I’m here is for what’s in the middle of this park. There is a massive monument for Simon Bolivar. You can see this bronze bust of him standing up, looking forward toward the city of Panama. He’s holding a scroll in one hand and leaning back, holding his big, long cape in the other. It says, “The nations of the Americas to our liberator, Simon Bolivar, 1826 June to 1926.” So obviously it was set up, this was made for the 100th anniversary of Simon Bolivar’s Congress, his Panama Congress.

So, remember Simone Bolivar? He’s the Liberator of the Americas. He was the guy from Caracas, Venezuela, who fought off the Spanish. He was one of the first to fight them off, and then spent the rest of his life doing that in country after country, which is why they call him the Great Liberator.

So his dream was a great Colombia, to unite all the different disparate, formerly Spanish colonies into one united Colombia. He really kicked things off in 1826, when he invited representatives from all the different countries that had just been freed to come and meet at one Congress to discuss how they could unite.

That Congress was held here in Panama at the exact spot that I am standing right now. It was the Bolivar Angostura Congress, or Panama Congress, and it was held at this convent, the San Francisco convent, which, at the time, stretched over this whole area. It was one of the oldest buildings in colonial Latin America at the time.

And so it was held right here. There’s a big plaque on this monument. It’s literally an image of Bolivar amidst all the other Congressional Congress members discussing the future.

And it’s interesting. In the image, he’s holding out his sword, but not in an aggressive manner. He’s holding the butt out to another man who’s reaching out to take it as the sign of we have to unite.

It’s amazing. It’s hard to even grasp what this moment meant, or it was, or what Simone Bolivar hoped this moment would mean for the newly liberated countries of Latin America. It’s amazing to walk right here.

And it’s all so fascinating because the location where they actually held it, the building is no longer here. This is one of those cases where it’s not actually buried, just underground. It’s like it’s gone, but it’s in our memory. And that’s what this big monument is, almost 200 years ago, held just three years after James Monroe made his speech.

Today, I am going to travel back to that time and then walk up to the present with historian Greg Grandin.

Greg Grandin: Well, my name is Greg Grandin, and I teach history at Yale University. And I’m the author of a number of books, the most recent one being The End of the Myth.

Michael Fox: Greg is also the former executive editor of the NACLA Report on the Americas, which co-produces this podcast. And he’s really prolific. He’s the author of numerous books focusing on US intervention in Latin America: The Last Colonial Massacre, Empire’s Workshop, The Blood of Guatemala, Kissinger’s Shadow, and so many more incredible reads. I’ll place links in the show notes.

I first interviewed him almost 20 years ago, and I’m so excited to feature his insight on Under the Shadow. I recorded this interview with him late last year, when I was just drafting the first few episodes of this podcast series, and before visiting the Bolivar monument in Panama City. We’ll be diving into Simon Bolivar’s Panama Congress, but also Monroe and the legacy of US imperialism in the region until today.

Here it is.

Michael Fox: So like I was mentioning, I want to start with the big picture, go all the way back. Obviously I’m talking about US intervention. If you could talk about the Monroe Doctrine, how it was created, why and how it laid the foundation for centuries of what we’ve seen in until then of US intervention and whatnot.

Greg Grandin: I mean, other countries have statements, we have doctrines. That’s the thing. And wasn’t really a doctrine. It’s the 200th anniversary, just a few days ago, of the Monroe Doctrine, meaning President James Monroe in the State of the Union address in which he delivers a transcript to Congress — At the time, he didn’t actually give the address — Talked about the United States’s relationship with soon to be independent countries within the Western Hemisphere.

In 1823, this was a moment in which it became clear that Spain had lost the Americas, except Cuba and Puerto Rico. But Bolivar had won his war. San Martin in Chile, Peru had won his wars. Argentina, Mexico were all going to be free.

In the United States, political elite people ran its foreign policy at the time. It was 1823, so we’re talking about three or four decades after independence. So it’s really talking about either the younger founders or second-generation political leaders of the United States: John Quincy Adams, John Calhoun, James Monroe, Henry Clay, senators from Tennessee, from Kentucky, that were very influential in foreign policy.

And they were trying to figure out what to do and say about what would soon be a free Spanish America, what the United States’s opinion was. There were a lot of things to consider, and mostly they were looking at that question. These are the Europeans. That their alliance with Great Britain, their rivalry with the Holy Roman Empire and Russia, their fear of France, and fear of an attempt to reconquer the Americas for the Bourbon crown. So there were a lot of things at stake.

I’d say the States had kept its cards, basically kept silent as these wars went on. The Spanish American war for independence wasn’t like the United States. They weren’t like a few years of fighting and a handful of battles, famous battles. They went on for decades. They started, basically, in 1810, and then went on to 1823, and they took place across the entire expanse of South America, Central America, and Mexico, and the Caribbean. These were bloody, destructive wars.

And the United States watched it all and held its counsel. They didn’t know what to do. On the one hand, they wanted Spain out of the Americas. On the other hand, they want these new nations to either form a single nation among themselves. And that wasn’t very likely, considering the geography, considering the political differences between them. And so they didn’t.

So they issued no grand pronouncements until Monroe did at the end of 1823, Dec. 2, 1823, in a statement that was mostly written by his secretary of state, John Quincy Adams.

The idea, at first, was to make an announcement, a joint announcement with Great Britain, to claim that no part of the Americas are open to reconquest. But Adams thought it was better if the United States just does it unilaterally.

The statement itself is very awkwardly constructed. It’s in different places in Monroe’s largest State of the Union message. It hedges, and it’s a very ambiguous statement. In many ways, the power of what becomes known as the Monroe Doctrine lies in that ambiguity. It could reconcile different positions.

So, just to break it down to its simplest components, you had people like Henry Clay who imagined creating what he called an American system that included Latin America, a large manufacturing and agricultural customs union, perhaps, but the United States as the core to the Latin American periphery. You might call that an early version of internationalism.

John Quincy Adams was, I don’t want to say he was an isolationist, but he was much more of a unilateralist. And he has a famous quote: There is an American system and it’s called the United States. Now, basically, we didn’t eat Latin America.

So what the Monroe Doctrine does is it allows for a reconciliation of all of these different positions, and it’s in its ambiguity. So basically the language of the Monroe Doctrine, as I said, it was scattered throughout this larger many-thousand word speech, and it was very vague what the intentions were. Basically, summed up, it said that “The free and independent nations of the two American continents were off limits for future colonization by any European power.”

And, Monroe let it be known that any effort to “extend Europe’s system to any portion of the hemisphere” would be viewed by the United States as a threat. That’s like the core of what we think of as the Monroe Doctrine. Monroe said that Europe is essentially different from the United States, but he doesn’t define what that difference is.

He talks about two different systems, and it’s implied that the two different systems are republicanism and imperial monarchism, but doesn’t quite come out and say that. He just talks about different systems.

And the United States would, despite making this very broad claim, continue to recognize Europe’s possession of areas of the New World that weren’t being contested, such as British Guyana or Canada, Jamaica, Cuba, and Puerto Rico, where there were no strong independence movements at the time.

What’s interesting about them, a royal doctrine, is that we think of it now as this doctrine of mandatory power where the United States is assigning to itself the role to police Latin America, as it had become right. There’s Theodore Roosevelt’s favorite corollary, where it assumes the United States has the right to impose its will on reckless or irresponsible nations.

But at the time, the Monroe Doctrine was celebrated by Latin Americans, by independent leaders. One, they were happy that the United States seemed to finally come out platinum for Spanish American independence. That was a huge thing. There were still a couple of big battles left before Spain finally gave up completely.

But the more important thing is that they read in the Monroe Doctrine a corollary to their own anti-colonialism. They didn’t read it as a doctrine of neocolonialism. They read it as a doctrine and as anti colonialism that no part of the Americas is eligible for reconquest. They saw it as analogous to their own anti colonialism.

So there were a lot of celebratory messages to Monroe from Latin American leaders, thanking him for the doctrine, not the doctrine, but for the pronouncement. And then, it wasn’t till later on that we could talk about how it evolves into what it became. But at first it was celebrated by Spanish America’s independent status.

Michael Fox: That’s so fascinating, Greg. We don’t even remember that history. Now I want to transition into what it evolved to. Why? And you mentioned the Roosevelt Corollary that I think is really key, which puts it into high gear. I guess the first question is, the 200 year anniversary. What would you say is its legacy today?

Greg Grandin: Well, I would say the Monroe Doctrine is kind of the gateway legal principle that allows the United States to reconcile idealism and realism or isolationism and internationalism. There’s something about the United States, where all those concepts are very slippery. Lies. Well, the Republicans are isolationist except for Latin America — Latin America is ours and we have to police it.

To say that, that’s a slippery slope towards a more robust globalism. So again, going back to its foundational vagueness and ambiguity. It allows the reconciliation of different political positions, and did it at its founding, and it continued to do so as it went on.

Woodrow Wilson, for instance, just give you an example. Woodrow Wilson was complicated. And I’m not carrying any water for Woodrow Wilson, but his relationship with Latin America, he did agree with Latin America that the heart of the Monroe Doctrine was a kind of anti colonialism, and that spirit of the Monroe Doctrine should become the basis of the League of Nations, a world doctrine.

When he kept on trying to sell the League of Nations, he kept on talking about the Monroe Doctrine in an expansive, generous sense, not as a police warrant, but as a principle of anti colonialism and national sovereignty.

But the pushback that Wilson got from conservatives who didn’t want to give up United States sovereignty, the people who eventually tanked the League of Nations and prevented the Senate from ratifying the League of Nations, they seized on the Monroe Doctrine. They wanted to know if the League of Nations was going to override the Monroe Doctrine, not allow the United States to act with mandatory power unilaterally wherever it need be.

And Wilson completely caved on that question. He started out talking about the League of Nations. If you want to know what the League of Nations is, look at the Monroe Doctrine, look at Pan Americanism. Look what we’ve done in the Americas. We’ve created a continent of free, sovereign nations. That’s what we want for the world. But in order to appease the nationalists on the chauvinists in Paris, he insisted, he totally gave in.

He gets a telegram from Senator Taft saying there’s no way that this is going to pass unless there’s some specific acknowledgement that the Monroe Doctrine is involved, is untouchable. And so Wilson has them insert in the charter of the League of Nations that regional understandings such as, especially the Monroe Doctrine, will not be affected.

So you see exactly the tension between the Monroe Doctrine as this anti colonial principle and the Monroe Doctrine as this assertion of national chauvinism and informal empire clashing. And most of the time, they don’t clash. Most of the time, they reconcile these different positions.

And so going back to the question, what has been its major legacy? It’s, in some ways, the gateway drug, or the gateway legal principle, through which the United States has been able to reconcile its different competing impulses from isolationism on one end of the spectrum to an international globalism on the other hand, other side of the spectrum, that happens in Latin America.

Michael Fox: Wow, Greg. If you were going to try and explain to somebody who just had no clue about its impact later over the many years, or what it’s become, the Monroe Doctrine and the excuses it’s been used for, invasions and things like that, how would you? I know this is a really big question. How do you do that?

Greg Grandin: You have to walk it back and bring it back to how it was seen by the Roosevelts of the world. I just gave the more Hegelian version of what the Monroe Doctrine is. But the fact of the matter is that when its power is asserted, it doesn’t really become a doctrine. It’s not cold.

The phrase “Monroe Doctrine” or “doctrine of Monroe” doesn’t come into circulation until about the 1850s or ‘60s, when the United States is in competition with Great Britain to build a canal through Nicaragua. And so that’s when the Monroe Doctrine gets asserted. The United States doesn’t have the power to enforce the hands off the Americas principle of the Monroe Doctrine till much later.

So what you see in the early [inaudible] of doctrine is Argentina asking the United States to intervene to stop the threat of Spain coming back, or Mexico doing the same, and the United States not being able to do or refusing to do anything. And so Latin Americans very quickly come to believe that Monroe Doctrine is, at best, ineffectual.

Then, as time goes on, the Monroe Doctrine becomes more of a doctrine of, as I mentioned, informal empire, mandatory power. And this is explicit with Theodore Roosevelt and his corollary, which says the Monroe Doctrine basically gives the United States the right to police the hemisphere. Another secretary of state I think said that the United States has sovereignty across the hemisphere, and that sovereignty is found in the Monroe Doctrine. It does become associated with interventionism, with regime change, with the United States’s meddling in Latin American affairs

So then what you see later, when it’s no longer acceptable to speak in the language of Theodore Roosevelt, where you have to at least pay lip service to Latin American sovereignty. If you Google “the Monroe Doctrine is dead” or “the Monroe Doctrine is over”, you’ll see, if you do an engram of it, there’s different moments.

Like after the pink tide, after Lula and Chavez were elected in the early 2000s, there were lots of essays about the end of the Monroe Doctrine. I think the Council of Hemisphere Affairs said the Monroe Doctrine is over. So there’s lots of declarations on the Monroe Doctrine being over. But now you listen to the Republicans and them once again explicitly reasserting the Monroe Doctrine. So it’s just this, it’s a totem. It’s a totem in US politics.

Michael Fox: It was super interesting, the guy who… I’m completely forgetting his name right now, but he was just voted out, he was the head of the House Republican, because he wasn’t strong enough.

Greg Grandin: Kevin McCarthy.

Michael Fox: Yeah, yeah, yeah. So he went and spoke. I found this clip online a couple weeks ago at Oxford, and it was a debate over US intervention. And so he starts off by saying, well, we all know that US intervention is good. And that’s the beginning of the rest of the game position of the United States had no right. So that was the right. OK, I get it. It’s still a thing. How is Manifest Destiny wrapped up into this?

Greg Grandin: Manifest Destiny is related in the sense that it’s about United States expansion. It was a phrase coined by John O’Sullivan, who was one of these expansionists that was around during the time of the annexation of Texas and the Mexican-American War, when pushing hard west to get to the Pacific.

There were a lot of different vectors of that propulsion. There was the desire to extend the country to diffuse the slavery conflict. The idea that free and slave states admitted one after the other but that basically just delayed the ultimate coming of the Civil War. But there was this idea that expansion would somehow resolve the problem.

There was the idea of expansion as a safety valve for workers, for the immigrants that were pouring in, that giving that free land would solve the problem of high rents and low wages in New York and in Boston. There was a clear sense that the West was valuable, that there was land and minerals, and that it was basically collateral for United States expansion. The United States could basically hold up the prospect of taking the West as collateral on loans to capitalize its development.

So there were a lot of drivers of Western expansion. And John O’Sullivan was of a generation that was called young America that saw Western expansion as keeping the United States young. And in some ways, it was a perverse corollary of the war of the revolutions of 1848 in Europe, where the wars and revolution of 1848 in Europe, they were all defeated and they were all put down, but at least they put the social question on the table.

They were the beginnings of labor parties and trade unions, and unions. There was this notion of a European spring. They were going to overthrow the old monarchs, and there would be a young Europe.

And the way that manifested in the United States was perversely not by fighting, not through class struggle against the oligarchs and the aristocrats upward, but fighting against Indians westward.

So John O’Sullivan was an ardent expansionist. He was a proponent of the war, of going to war in Mexico, to take Mexico to get to the Pacific, and he came up with the expression “Manifest Destiny”. That the United States’s manifest destiny is to occupy the continent fully.

And it’s a very subjectivist, romantic galleon sentiment, that there’s potential manifest within the thing itself, that being and becoming that, what the United States is not yet, and it will be when it fills out the continent. That’s the expression “Manifest Destiny”.

Even young Walt Whitman, who later on repents from his imperialism. He was gung ho about the Mexican-American war. He thought the United States should take all of Mexico. So there were also debates within the United States about how much of Mexico the United States should take and raze. Factors into that is that there wasn’t all Mexico movement after the United States defeated Mexico in 1848.

But also there was concern that maybe, particularly among Southern slavers, that maybe the United states should only take the sparsely populated northern parts of Mexico rather than those parts down south with all of those troublesome Native Americans. So it’s interesting the way those debates intersect between imperialism and racism.

Michael Fox: Yeah, absolutely. Greg, I want to walk back to the Monroe Doctrine moment, 1820s. Was there a time? And it’s interesting. So one of the things I want to do in Panama City is go to the place where Bolivar held his Panama Congress, because that was this moment where there’s the United States, but there’s also this possibility of Gran Colombia maybe uniting all the rest of Latin America.

Could we look at that moment as a time where things could have gone differently had the Latin American countries been able to unite in a different way? Talk a little bit about that moment.

Greg Grandin: Bolivar, the wars of Spanish independence end around 1823 to 1824. And Bolivar had, earlier in his letter from Jamaica, talked about thinking about America as a large confederation. By the 1820s, he was clear that it wouldn’t be a single nation. There was too much division. Competition among the different political classes of each, Peru and Chile and Mexico. But he still hoped that there could be a confederation.

The thing about how we talk about American exceptionalism, and we tend to think of American exceptionalism as unique to the United States. But the independence leaders of Spanish America saw the New World as an exceptional place, as a place where humanity would be renovated, would be redeemed, in which the old superstitious monarchies would be overthrown, where a new kind of republicanism would allow for the fullest expression of human freedom.

Spanish American Republicans tended to be more ambitious in their vision of what a just society is; They understood that slavery had to end, that abolition and emancipation would be part of it. That didn’t happen everywhere at the same time in Spanish America because of political conditions and conditions on the ground.

But there was a sense among independence leaders that it was non negotiable. Independence from Spain meant emancipation from slavery, whereas that wasn’t necessarily the case in the United States.

So one of the topics on the agenda in 1826 was to talk about New World abolition. Another topic on the agenda was the internationalization of the Monroe Doctrine: How do we turn the Monroe Doctrine into international law? And by that they meant anti colonialism. Latin Americans came up with a different theory of sovereignty.

But to just go back to that original speech, or the statement or the State of the Union address that Monroe forwarded to Congress, there’s another part of that speech that actually spends a good deal of time talking about Westward expansion and how vital and vibrant the United States was that it was moving Westward — This was 1823 — That the Indian tribes were receding as the white man advances. This was basically the theory of US sovereignty.

So Latin Americans could read one paragraph of that statement and think that the United States is talking about and is affirming, is renouncing a doctrine of conquest and anti colonialism. But if they read the whole thing, they would see that its theory of sovereignty was actually an affirmation of the doctrine of conquest, moving West and taking Indian land.

Latin Americans, on the other hand, didn’t have that option. Latin Americans didn’t have the option of endless expansion as a theory of republican sovereignty because they had to deal with each other.

This is the thing about the difference between the United States was bull came into the world a single child. It didn’t. It had decrepit European empires with barely a hold on their territory to the West and Indigenous communities that they knew would just recede away with time as civilization progressed.

But Spanish America came into being as an already conceived community of nations. The thing is that they both legitimated and threatened the other. They legitimated the other themselves because independence confirmed that the overthrow of Spanish Catholic royalism was legitimate, but they threatened because, under the old doctrine of conquest understood as international law, war was legitimate and conquest was legitimate.

What would stop Argentina from saying our destiny lies and climbing the Andes and taking Chile and making it to the Pacific? Why would you not want to get to the Pacific, just like the United States wanted to get to the Pacific? Well, it couldn’t, because these nations were already [here], they had to figure out how to live with each other.

And the way they did that was a doctrine of sovereignty that affirmed the volatility of borders, the Roman law doctrine, as you possess Ute posted. But they basically said, look, Spain, we have to take Spanish borders as they exist in 1810. And these are the borders that we have, and we can’t fight.

Now, the fact of the matter is that what conflicts there were, there were territorial skirmishes over where the borders lay, especially if resources were involved. We see the same thing now with Venezuela and Guyana. But they affirm the principle that borders were untouchable and nations were sovereign within those borders. That’s a very different definition of sovereignty than the United States had.

So, Bolivar said that one of the items on the agenda was to affirm the Monroe Doctrine as international law, that’s what he meant. He meant a firm revocation of the doctrine of conquest and an affirmation of anti colonialism and anti conquest and anti interventionism.

Now what happens is that the United States, when John Quincy Adams, who’s the president at the time, and he’s the last president before Jacksonians take over, and there’s this shift in the balance of US power away from the founders of the Tidewater Virginia Gentry and the Boston Brahmins, away from them towards the West and the South, toward the settlers and the slavers with Andrew Jackson’s 1828 election.

But when Adams suggests sending two observers to this Congress, he sets off a four-month debate within the US House of Representatives that basically involves all of the main players of what would become the Jacksonian Coalition. Merely being invited to an international conference in which they would discuss the abolition of slavery, the recognition of Haiti, and the internationalization of the Monroe Doctrine threw them into a tizzy, and it basically helped coalesce what became the Jacksonian Coalition.

Adams eventually gets an authorization to send two observers. One of them dies along the way. The other one arrives after the conference is over. The conference was a bust. It’s the most important conference.

Michael Fox: Oh, gosh, Greg, I want to fast forward a little bit in the direction of more recent history. One of the things I was fascinated by in your book Empire’s Workshop when reading it again was death squads and the US. They’re basically a brainchild of the United States, right? Like the US sees this as a means of putting pressure and using violence as a means to push, in terms of its larger counterinsurgency strategy and whatnot in the 1960s and ‘70s. Can you talk a little bit about this? What is it, what does it mean? How are they being implemented, and why is it so important to the United States?

Greg Grandin: Well, death squads and the use of parapolitics or extrajudicial repression is not new and it’s not, I don’t think, particularly unique to the United States. Landlords rely on strongmen in order to secure their property. But what happened, certainly in Latin America, there was use of paramilitaries and judicial repression prior to the Cold War.

But what happens after the Cuban Revolution? It’s really the Cuban Revolution that galvanizes the United States to begin to what they call professionalize the security forces in Latin America. Policymakers in Washington have this vision of Latin America as being fairly incompetent and that there are these competing security agencies.

Maybe there’s something to the equivalent of a Treasury police or border police. That’s the regular police. There’s a military and everything. They’re run by gangsters that are more interested in consolidating their jurisdiction and their collections than they are in being professional guardians of national security.

So the United States spends up, goes into Latin America in 1960 and really begins to work, spends an enormous amount of money and energy on what they call professionalizing and centralizing the Central Intelligence Agency, centralizing the security agencies of allied nations. And it means replacing more thuggish figures with people that are more committed to fighting communism, that have close ties to the United States through these security programs and training programs.

What it means on the ground is getting these units capable of capturing individuals,

extracting information through torture, and then acting on that information to act on a wider radius, and then do it again and again and again. And also included in this is the storage of information. What do you do with the information? How do you analyze it? How do you collate it? So basically it’s about creating little Central Intelligence Agencies in all of these Latin American nations that are effective, that are rapid response.

So evidence seems to suggest that Venezuela and Guatemala were the two countries in which the United States was very much involved in creating these agencies that were able to carry out collective disappearances, collective kidnappings, apprehensions, and then interrogating the prisoners, and then acting again to capture even more.

So, for instance, the classic one that I talk about in Guatemala is in 1966. John Lungan, he starts off as an Oklahoma sheriff, then he works for the Border Patrol, then he’s involved in Operation Wetback in 1954. Then he, at some point, joins the CIA through its public safety program, which is the name of basically the front group for the CIA to train Latin American police and security forces.

And so he goes to Latin America right before this key election in 1966, in which a reformer is running, promising to be the third government of the revolution, meaning the United States overthrew Arbenz in 1954. The first government was Arevalo. The second government was Arbenz. Montenegro was going to be the third government of the revolution, and the fledgling armed left makes a decision to support him.

And a lot of these people in what is the armed left in Guatemala in 1966, a really old lab and support what is Barack Obama’s that had to go underground. And they’re trying to figure out whether they can recreate the political coalitions that led to the election of Arbenz in this new Haydn period of repression, or do they need to adopt more militant tactics like the Cuban Revolution? And there’s debates, but they decide that they’re going to tell these supporters to vote for Julio Montenegro because he did seem like a sincere reformer.

John Longan arrives in March, a couple of weeks before the election, and puts into place what he calls Operational Piezo, Operation Cleanup, in which a security unit captures a handful of people, tortures them, gets information. All told, 33 people were captured, tortured, and killed within that period, and then their bodies were dumped in the ocean from helicopters. They were just disposed of.

So I called that the first obvious disappearances and kidnappings and extradited killings that preceded it. But this really does mark a turning point in the rhythm of repression. The fact that the information is being gathered more quickly through more effective means of torture. It’s then being acted on more quickly because they’ve integrated the security forces of any given nation.

And then there’s an acceleration, there’s almost an acceleration of time. And the fact that a lot of the people who disappeared were more the moderates, people who wanted to work through electoral politics, they were eliminated. So that eliminates the middle ground. It creates the conditions for more political polarization and extremism on both sides. So this is part of the process. And this happens in every country.

And you can think of Operation Condor as that process on a continental scale. So you’re integrating the security forces of any given nation, and you get that integration locked down and functioning. And what you do is you begin to integrate the security agencies of nations into a larger transnational consortium. That’s what Operation Condor is, that on a larger scale.

So in the ‘60s, you see it happening on the national level. By the time you get to the ‘70s, it’s happening on a continental level.

Michael Fox: Greg, so there’s this question that’s been lingering in the back of my head. Would love your thoughts on this. Was this all ever about spreading democracy and freedom? ‘Cause if you do a poll, probably half the United States would still say, yeah, we’re benevolent and it’s good, almost like we’re like Santa Claus bringing freedom and democracy around the world.

Was it ever about that or is that just the discourse? When did that discourse get synced up with the foreign policy and whatever else? I know in Reagan’s time he started to do more of that talk about human rights and stuff even, and pick up more things from the left and progressive sectors to try and win the media campaign. Anyway, I’ll leave it with you.

Greg Grandin: For a long time it was the Democratic Party that was the party of idealism in the sense of justifying interventionism abroad through these high ideals. JFK and the Alliance for Progress was the high point of that. The lines were that progress was going to complete the revolution of the Americas and bring development. It’s also a moment of Keynesian economics where the welfare state is seen as the end point of history.

And, of course, there were structural reasons why the global political economy produces immiseration in these countries. That isn’t going to be overcome through the kind of reforms the Alliance for Progress were proposing. But they still had that rhetoric, that the idea was to bring development and raise the standard of living. And that’s how you prevent revolution.

The Republicans tended to always be the party to shy away from that kind of high flying rhetoric and really talk about order, and if we had to intervene, we’re basically doing it for national security reasons.

That’s what does switch with Reagan. That is what is consequential about Central America in the 1980s, is that Reagan, remoralizes US power, and he remoralizes capitalism, And the free market becomes a site of freedom and a site of creativity. And Reagan is central to this and support for the countries and support for death squad states in Guatemala and El Salvador.

Reagan was shameless in talking about these people capable of committing the worst savagery as the moral equivalent of the founding fathers. Like Thomas Paine, we have the power to begin the world anew, and it goes to first principles.

And this is why Chile in 1973 is so important. And this is why the libertarians are so… It’s not because there aren’t larger historical and structural processes and changes that bring about neoliberalism. It’s not like neoliberalism is hatched in the mind of a Friedrich kayak. But they do talk about it in foundational, first principle ways.

So you know what’s at stake. So when they talked about overthrowing Allende, they were open about the need for repression, that you have to force people to freedom, that you have to force people into democracy, that Allende was the terminus of a 70-year period of a false conception of democracy, social democracy, social welfare. And we have to strip all of that away.

And even if it means a 17-year dictatorship, we’re educating people in freedom. And because they see freedom, they see democracy as in the free market, in the protection of private property and in, supposedly, individual choice — Except when they accept, when they choose to have National Health care. Whether it’s hypocrisy or not ideology operates on different levels, I think, and different registers.

A lot of it is just like foam that washes off of people. Oh yeah, yeah we’re doing that, and only the dimmest perception of what’s going on anywhere. And then there’s other people that are like that, that in every event a referendum over first principles, the election in Argentina, Melei, he’s one of these true believers.

Michael Fox: It’s so complicated.

Greg Grandin: It is complicated.

Michael Fox: There’s so many layers. I want to talk a little bit about the Contra war. I feel like it’s completely lost in the past, and usually amongst society chalked up to, oh, a few bad apples. Yeah, that Ollie North guy, he testified a bunch and yeah, he did some really bad things. But this was a thing that was stretched across operations amongst major portions of the US government, the CIA, State Department, whatever else. Talk about how important this was, how it involved the CIA, and why this was so important for Reagan and the US at that time?

Greg Grandin: Well, I think that Central America in general — And the bigger point is, I use this in the book Empire’s Workshop, Gene Kirkpatrick, who’s Reagan’s ambassador to the United Nations that Reagan elevated to secretary level position, she called Central America the most important place in the world for the United States, critically important.

This is 1982. There’s a lot of things happening in 1982: Israel’s war in Lebanon, the aftermath of genocide in Cambodia. There’s nuclear arms treaties. There’s a lot of things going on. And to call Central America the most important place in the world for the United States is an interesting quote.

And the way I think about it is that it was the most important place in the world because it was the least important place in the world. It was a place that had no significant patrons that the United States had to worry about. It had no nuclear arms. It had no major resources other than coffee and sugar. So Reagan can give the region to the movement ideologues that brought him to power.

Reagan had to act more cautiously in the rest of the world. Reagan came to power saying he was going to sweep it all away, he was going to confront the Soviet Union. He left that mic on. We didn’t begin bombing in 5 minutes or that whole thing. But the fact of the matter is that Reagan acted quite cautiously everywhere except Central America because he could give it to the base, the activists, the true believers.

And that base was composed of different components that were the religious right, that was the neoconservatives. There were the revanchists who were angry that they lost Vietnam. There were general mercenaries. There were a lot of different sectors within the conservative movement that came together in Central America.

When Reagan came to power, Central America was in a boil. The Sandinistas had just won, defeated the Somoza regime, and the Contra war hadn’t yet gotten started. It looked like insurgencies might very well do the same in El Salvador and in Guatemala. And of course, this was all going on as the United States just lost Iran in 1979. So the United States couldn’t do anything in Iran, but they could do something in Nicaragua. And those two things uncannily came together when the United States, when Reagan sold high tech weapons.

And the larger context of this is that you have a Democratic controlled Congress that doesn’t want to restock the Cold War necessarily. The Democrats wind up going along with Reagan and not really putting up major opposition. But for the most part, there’s still a lot of these post Watergate, post Vietnam checks on executive power.

So I mean, we know the story. The agents of the United States, Oliver North, William Poindexter and people like that begin a very complicated fundraising regime which included selling high tech weapons to Iran to the ayatollahs and mullahs in Iran and using the money to fund the Contras. They also began at the same time fundraising in other ways.

So these all new emerging presidential coalitions workout their international alliances, and it was through Central America that the New Right made its ties with conservative Gulf countries. Saudi Arabia kicked in money, Israel kicked in money, private sector, Ross Perot kicked in money for the Contras. Then there was a lot of grassroots fundraising from the religious right to support the Contras.

So the Contra war becomes this crusade for the New Right. And the fact that the Sandinistas were as much Christian as they were Marxists. The rise of liberation theology at the same time as the rise of Evangelical Christianity puts these two very different versions of Christianity on a collision course. And the crash site is Nicaragua. So a lot of the Christian right sees in Nicaragua a kind of Holy War before they move on to political Islam. It’s liberation theology that they have to contest.

And what’s often not discussed about, we talked about first principles, is that a lot of the revitalization of the free market as a site of human fulfillment and creativity wasn’t just a secular project. The Hayeks and the von Mises Christian New Right had their economists. You don’t know about them because they’re kind of obscure, but they were arguing against liberation theology point by point.

Where liberation theology said that the free market was an amoral site of greed and unholy competition, they said that the market was the place where God’s grace was manifest, where the virtuous were rewarded and the wicked punished. Where the liberation theologians said that if you look at the global political economy with desperately poor, crisis stricken nations and a handful of nations with more wealth than than than than Jehovah himself, the Christian right economists said that reflects God’s grace, that these countries are poor because they deserve to be poor because they live in sin. And this is straight out of some medieval stuff updated for the 20th century.

So the Contra war becomes this real crucible of the New Right. It brings together these different constituencies, theocons and neocons and militarists, and it allows for not a reactive response to liberation theology, but a proactive response, taking on the arguments themselves. And it also created the covert network that bound these coalitions together, these fundraising coalitions and these covert operatives. And it also began to lay the justification for the rehabilitation of an imperial presidency.

So if you jump forward ahead to the Iran Contra hearings, the Democrats basically focused on procedural issues. They didn’t question the United States’s right to try to contain the Sandinistas. They agreed with Reagan that the Sandinistas were a problem, they just didn’t think that the United States should be running a covert war against the Sandinistas. They focused mostly on a rogue National Security Agency that was basically running wild and needed to be reined in.

They issued a report. The dissenting report was written by Richard, Dick Cheney, who was a congressman from Wyoming at the time. And he puts forth what becomes known as the theory of unitary power that, at the time, was seen as too extreme and invested in the executive branch, the ability to wage war wherever it wanted to wage war, etcetera. That’s in 1986, 1987.

Jump forward to 2003, the theory of unitary powers basically is on the table. It’s what they use openly to justify the war on terror.

So Central America is marginal, but it’s on the margins where this coalition is worked out and where they field test their ideas, they field test their strategies, and then it becomes mainstream.

Michael Fox: Amazing, Greg, thank you.

OK, to close this out here. Why is this history of US involvement, particularly in Central America, ’cause that’s my focus on the podcast, but in Latin American general, why is this important today? Why is this important for a US audience today?

Greg Grandin: Look at the world today. And you look at the war in Gaza, and the war in Ukraine, and the inability to deal with climate change, and these serial crises that are engulfing the world, what do you wanna call them? The polycrisis or the multi-form crisis, whatever you wanna call it. What’s striking is the lack of imagination of a political class to imagine a way forward.

Even before the war in Gaza broke out, what was the vision of what was supposed to be in place once the Ukraine war ended if Russia was defeated? Nothing but an old school balance of power with the United States locked into competition with China.

Latin America has a million problems, but for the most part, it’s a region that actually functions. There’s no interstate wars. They have a vital and vibrant left that still wins elections. Obviously, the right is still strong and it makes its comebacks, but they still have a vision of citizenship, that social citizenship, that democracy means not just the right to vote, but that actually the right to demand a dignified life of healthcare and education.

So I think that Latin America is important in that way as the United States bungles around and tries to figure out… Hopefully there will be a new reform ruling coalition or at least a new coalition. And they could look to Latin America for ideas.

I mean, you go back to 1933, it was Latin America. Roosevelt turned to Latin America to revitalize liberalism. This is a whole other story which we don’t have time to go into, but the New Deal took a lot of its ideas from Latin America. And to a large degree, Roosevelt was able to redeem liberalism, revitalize it and inject it with a new animating spirit, through what was going on in the Mexican Revolution, truly accepting the sovereignty of individual nations.

So you could imagine Latin America serving as a model. Petro in Colombia has ideas for how to get off fossil fuels. There’s proposals for how to end the drug war. Lula has a vision of what a new international order should look like that wasn’t just based on balance of power.

There are ideas in Latin America that could serve as a template for some of the crises that we seem to be engulfed in and that seem to be intractable.

Michael Fox: Amen to that. Thank you so much, I really, really appreciate it. This is so great.

That is all for Under the Shadow.

As always, if you like what you hear, please check out my Patreon page: patreon.com/mfox. There, you can see pictures of the Simon Bolivar monument in downtown Panama City. You can also support my work, become a monthly sustainer, or sign up to stay abreast of the latest on this podcast and my other reporting across Latin America.

Under the Shadow is a co-production in partnership with The Real News and NACLA.

The theme music is by my band, Monte Perdido.

This is Michael Fox. Many thanks.

See you next time…