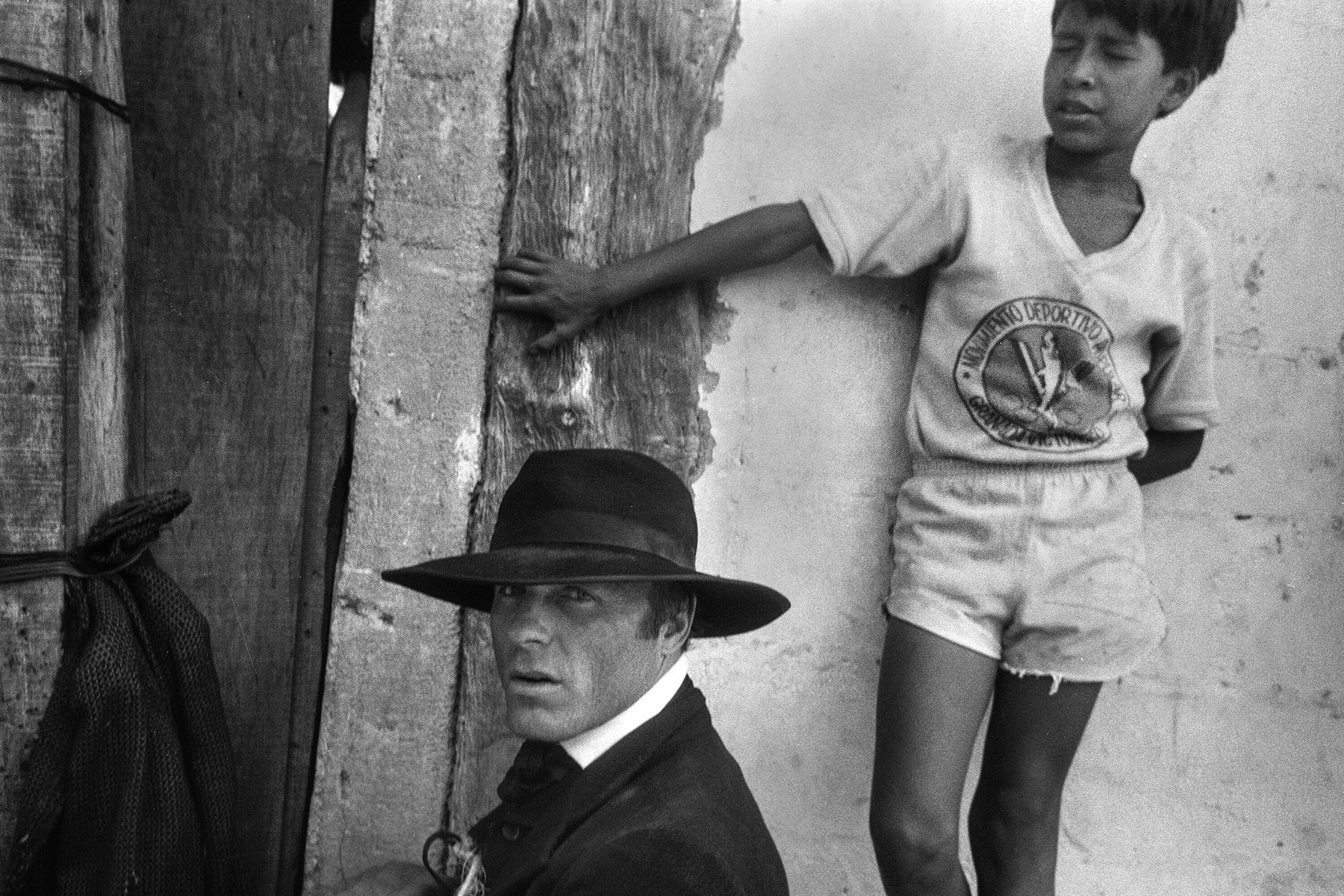

In the late 1980s, British film director Alex Cox spent several months in Nicaragua filming Walker, a movie about the U.S. filibuster who invaded and took over the country in the mid-1800s.

As Cox puts it, he was trying to make “a revolutionary film in a revolutionary context.” That did not go over well in Hollywood. The movie would get him blacklisted. Even today, you still can’t find the movie streaming.

In this bonus episode for Under the Shadow, host Michael Fox speaks with Cox about his 1987 movie Walker and his filming of the movie in Nicaragua in the 1980s. They also look at U.S. intervention and the film industry.

Under the Shadow is an investigative narrative podcast series that walks back in time, telling the story of the past by visiting momentous places in the present.

In each episode, host Michael Fox takes us to a location where something historic happened — a landmark of revolutionary struggle or foreign intervention. Today, it might look like a random street corner, a church, a mall, a monument, or a museum. But every place he takes us was once the site of history-making events that shook countries, impacted lives, and left deep marks on the world.

Hosted by Latin America-based journalist Michael Fox.

This podcast is produced in partnership between The Real News Network and NACLA.

Guests: Alex Cox

You can listen to the first episode of Michael Fox’s new podcast, Panamerican Dispatch, here.

Follow and support him and Under the Shadow, at https://www.patreon.com/mfox

Theme music by Monte Perdido and Michael Fox.

Monte Perdido’s new album Ofrenda is now out. You can listen to the full album on Spotify, Deezer, Apple Music, YouTube or wherever you listen to music.

Other music from Blue Dot Sessions.

Here is the Trailer to Alex Cox’s movie Walker: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XImi7fT7-J0

You can purchase the DVD to the movie Walker, here: https://www.amazon.com/Walker-Criterion-Collection-Marlee-Matlin/dp/B000ZM1MJ6

You can hear Joe Strummer’s soundtrack to Walker, here.

And, if you liked this episode, don’t forget to check out Episode 8 of Under the Shadow that looks back on William Walker.

Transcript

Michael Fox: Hi, I’m your host, Michael Fox.

So, the last couple of weeks have been really busy for me. I was in southern Brazil covering the impact of the tremendous flooding there. You can find links to some of my reporting in the show notes.

I’ve also just launched a bi-weekly podcast that’s a bit of a postcard from the field. I’m calling it Panamerican Dispatch, and it’s available exclusively for my supporters on Patreon. The first episode is a personal reflection on my reporting in southern Brazil in recent weeks: what I saw, what I felt, what the situation on the ground is, and what to expect going forward. Please check it out, and I appreciate the support. You can find it at www.patreon.com/mfox. The link is also in the show notes.

As you may have guessed, all of that means that I’m still working on the latest episode of Under the Shadow. That’ll come out in two weeks. But in the meantime, I bring you this.

[INTERVIEW EXCERPT BEGINS]

Alex, would you introduce yourself?

Alex Cox: Yes, my name is Alex Cox. I’m a film director, writer, and actor, and I directed a film in 1987 called Walker about the American filibuster and regenerator William Walker.

[INTERVIEW EXCERPT ENDS]

Michael Fox: Alex is also the British film director who made the cult classic Repo Man back in the 1980s. If you’ve been listening to the last few episodes of Under the Shadow, you’ve heard his name before.

I sat down with him for this interview a couple of months ago. I bring it to you now in its entirety.

Now, I know we discussed Walker at length in the eighth episode, but this interview with Alex Cox is fascinating because it straddles the past and the present. We discuss his filming of the movie Walker in Nicaragua in the 1980s.

We also look at US intervention and the film industry, which basically blacklisted Alex for making Walker. You still can’t find the film streaming online. As he puts it, he was trying to make a revolutionary movie in a revolutionary context. He filmed it in 1980s Nicaragua. That did not go over well in Hollywood.

One final thing to note before we get started. Toward the end of the interview, I mention Joe Strummer. He was the lead singer for the British punk band The Clash, and he wrote the soundtrack for Alex’s film Walker. I wanted to make sure everyone was in the loop.

OK. Here’s the interview…

[INTERVIEW BEGINS]

Michael Fox: How did you get interested in Walker, Alex?

Alex Cox: I was interested primarily in Nicaragua because I remember when the revolution happened in ‘79. I was in America, I was in Los Angeles going to UCLA. And the initial response of the American media, the LA Times, New York Times, was very favorable, because obviously Somoza was a son of a bitch, and the American media were going along with, yeah, they got rid of the dictator, hooray. And the Sandinistas, some of the more cool Panama hats, they look good in photographs. That lasted for a couple of months.

And then the media just switched. It turned, as they say, on a dime. 180 degree hostility towards the Sandinistas – The Sandinistas had betrayed the promise of the revolution, et cetera. That happened so quickly.

That was the first time I actually witnessed the propaganda machine at work. Obviously, I lived through the Vietnam War, so I remember the propaganda machine, but the propaganda in favor of the American war in Vietnam was a constant, whether it was the BBC or The Guardian or the Times or any newspaper, they were all totally in favor of the American war in Vietnam.

Whereas this was an instance where the mainstream media had said one thing one week and then reversed themselves the following week. We’re used to this now. This happens all the time now; there are Nazis in Ukraine until there aren’t any Nazis in Ukraine. But it was surprising to me at that time to see that happen because it didn’t happen so rapidly and so constantly as it happens with the media now.

And so, I was interested in learning more about Nicaragua. So I and my friend Peter McCarthy, who was a film producer and director, also ex-UCLA. He and I, in the early ‘80s, went down on one of those leftist tours. You go and travel around and you see the farm cooperative, and you meet the representatives of the political parties, et cetera. So we went on one of those trips and it was very interesting. I really enjoyed it.

There was still passenger rail in Nicaragua, and I think the most exciting thing for me was to get to go on this little local train that went from Granada to Managua. We stayed in Granada because it was election time. It was the ‘83 election, I think, when the Sandinistas were elected to power. So we couldn’t stay in Managua because all the hotels were full of journalists. So we ended up in Granada. How lucky we were, because Granada is so beautiful.

And on election day, we were in a hotel in Granada. We were sitting there — Because it was election day, you couldn’t buy beer. There were no alcohol sales, but in the hotel you get a beer. And so we were in the hotel, and there were a couple of guys, Nicaraguan guys there as well.

They were young men, our age or even younger, who had been invalided out of the Contra war, which was already going. One of them had shrapnel injuries. They were looking to get educated and do more stuff in support of the revolution.

And so they said, what do you do? And, and we go, oh, well, we’re filmmakers from LA. And they say, well, you should come here and make a film about the situation here. And we started giving them a load of bullshit like, oh, well, you know, the thing is, it’s very hard to make a film, it costs a lot of money, it’s very hard to obtain the money, it’s a very conservative kind of environment.

And these guys weren’t having it at all. They’re saying, look, we made a revolution here. We got rid of the dictator. You can go home and make a film at least, can’t you? And so we were put on the spot, or I thought I was put on the spot, and I thought, I better had try and make a film set in Nicaragua.

So I went back to Los Angeles. I knew a Catholic priest called Blase Bonpane who was very in favor of the Sandinista movement. He put me in touch with a historian, a guy at UCLA, a professor called Bradford Burns, who actually was a very interesting writer, I later discovered. I hadn’t read anything by him at the time. Bradford Burns lent me his library card, and so I was able to go to the UCLA library and check out all these books.

Because I’d seen this sign on the wall on one of the walls in Granada which said, this is the place where William Walker did such and such, burned the town or violated this church or whatever. There was a plaque on the wall about William Walker.

The more I read about Nicaraguan history and the more I read about William Walker, I thought, this is an amazing story which nobody knows about. Here is a guy who, at the time of Franklin Pierce, was more famous than the president.

There were more column inches about him in newspapers in the United States than about anybody else. William Walker was a phenomenon. He was kind of the Trump of his day, except even more popular and greatly approved of by all. And so I thought, this is a story that deserves to be told.

And so I started working on the script with an American writer called Rudy Wurlitzer, and trying to raise money with a Peruvian producer, a friend of mine, Lorenzo O’Brien. And together, amazingly enough, we actually did it. We we managed to raise the money — $5.6 million to spend in Nicaragua on a film about William Walker. And that was what we did.

Michael Fox: Amazing, amazing. So before I dive into a little bit more of the filmmaking, what was the feeling on the ground that first time you went there, in the early ‘80s? What are your memories of what it felt like, what the vibe was while you were there?

Alex Cox: It was very positive. It was tremendously positive and very enthusiastic. Everybody — Well, I mean, not everybody, but the vast majority of the people whom I met supported the revolution and supported the Sandinistas.

Then, over the four years that I was there going back and forth, it did change because the Contra War enacted such a heavy toll, that everybody had a family member who had been killed or impacted or forced to leave their farm because of the American-financed terrorism of the Contras. And so it did become more difficult.

You can see how we were very privileged because we were foreigners. We were staying in hotels. There was food for us. But as the Contra War dragged on, it became more and more difficult for the people, the real Nicaraguans.

Michael Fox: Talk a little bit about your filming there? When was that, in ‘86 or ‘87, that you all were down?

Alex Cox: I think it was 1987 that we filmed Walker.

Michael Fox: And how many people were with you? Describe a little bit how that went down.

And were you concerned about, ’cause you were literally filming in Nicaragua while Nicaragua was in the middle of this Contra War while they’re fighting the Contras, were you concerned for safety and whatnot at the time?

Alex Cox: I think some of the actors were concerned for their safety because actors are very fragile and need a lot of support, a lot of reassurance. I was totally into it. I was like, man, I’m in the middle of a revolution. This is great! My naivete because I had a very simplistic view of things, and, of course, I also had a ticket home, which the Nicaraguans didn’t.

But it was fascinating. It was absolutely fascinating. The amount of support that we received both from the government, from the people, even from non-aligned or enemy entities like the Catholic Church were all supportive of the production of the film.

And we caused a lot of problems. The streets of Granada were beautifully paved, and we came in with a whole bunch of dirt and dumped it on the main Plaza and all the surrounding streets in the middle of Granada.

Many years later, I went to an event in Venezuela, in Caracas, and I met again Ernesto Cardinal, who had been the minister of culture when we were making Walker. And there was Ernesto Cardinal in his white outfit, as always, and I go up to him and I go, oh, Don Ernesto, you won’t remember me, but I’m Alex Cox, I directed that film Walker. And he goes, oh, yeah, you were the guy who caused all the problems with respiratory ailments in Granada, weren’t you [laughs]? So Ernesto Cardenal put me in my place.

Michael Fox: Wow, wow. How big was your team? How long were you there, how long did filming go on for while you were there?

Alex Cox: We shot for 9 weeks. The crew was almost entirely Mexican, and they were coming via road from Mexico City. They were delayed for quite some time, I think for political reasons, crossing various borders to get to Nicaragua. So the shoot actually began a week late.

I and the executive producer and Ed Harris all put our salaries back into the project in order to pay for that week of actors hanging around. We couldn’t shoot with them because the crew hadn’t arrived. We didn’t have the cameras. So we had all the actors on hold for a week.

But once the crew arrived, then we had a nine-week shoot; in the cathedral, in Managua, in Granada, in Rivas, San Juan del Sur, Ometepe.

Michael Fox: Amazing. It’s so powerful to be thinking about this moment, talking with you. Because these are all places that, over the last year, I’ve been to on numerous occasions, so I know the exact route.

And even this story of understanding William Walker, it’s a story that, it’s funny, with Under the Shadow. It’s a story that I’ve known for years, if not decades, probably very much thanks to your movie. But then when I decided to do this podcast, the very first thing that I knew I had to do was something on William Walker. That was like, I can’t wait to do this episode because it’s such a crazy, crazy history.

So, the thing that I really appreciate about your work and your film is this crossing over the time between the past… It’s like mixing the 1850s and 1980s. How did that come to mind? Did you say, hey, let’s, let’s do this a little bit different. Let’s not just do this a normal biopic. Talk a little bit about what that meant, what you were trying to say with that?

Alex Cox: Well, Rudy and I both, and Lorenzo as well, we, all three of us, had this idea that we didn’t want to make one of those Hollywood-type films where the protagonist is like the good journalist who goes down to the bad place but sees everything clearly, and tells the truth, which is the template of Salvador, or of The Year of Living Dangerously, Under Fire. That’s the American way of doing things, is we always have to have a sympathetic character, to see through that person’s eyes. Journalists, of course, are always totally sympathetic and impartial and honest.

And so we didn’t believe any of that bullshit. There are no good people involved in this because even the Nicaraguans with whom Walker interacts, they’re oligarchical monstrosities. They’re just fighting the civil war against each other, killing thousands of poor peasants who’ve been impressed into their armies so that either the conservatives or the liberals can be in charge. Nothing has changed, right? At least, nothing’s changed over here. Things have changed in Nicaragua, fortunately.

But so it was that we’re going to make a film that doesn’t abide by these conventional parameters. So having decided that and having decided there were no sympathetic characters in the story — Except for Ellen Martin, who dies very early on — It was easy to say, well then, why are we even sticking to a traditional historical template?

Why not say that this is reality, this isn’t just something that happened in the 1850s? This is something that’s happening right now, today, as once again we intervene, not even in the civil war, because it wasn’t a civil war. We created a state of civil war in Nicaragua in order to justify intervention there.

Michael Fox: Amazing.

Alex, people today, looking back on your film, looking back on this history, what legacy does it have today? Why is it important to remember this now?

Alex Cox: Remember William Walker?

Michael Fox: To remember William Walker and to remember your film. I think those are two different questions.

Alex Cox: Well, there’s no real reason to remember the film unless it’s good. If it’s a good film, then it will endure. I think it’s a very good film, I like it a lot, so I think it endures on its own lights.

And, partially, it endures because it isn’t like Salvador or The Year of Living Dangerously or Under Fire. It’s attempting to be a revolutionary film in a revolutionary context. And that was a great deal more fun. That’s what gives the film its longevity, if it has longevity, I think.

But the other problem is it has longevity because nothing has changed. Well, I shouldn’t say nothing has changed, because the political situation within Nicaragua has changed. But the desire of the Americans and also the Western Europeans to frustrate the Nicaraguan revolution seems to be as strong as ever.

And that was interesting to me as well to realize it wasn’t just the Americans. The Europeans are every bit as bad in terms of being a yapping gang of capitalist, imperialist poodles. I’m ashamed to come from Europe or wherever it is I come from because we should know better than just following them in this discredited path. But anyway.

Michael Fox: That’s been one of the most fascinating things about this podcast. I’ve known all these stories on the surface or a little bit underneath, but actually going to places and walking in footsteps of things that happen. And then, whether it’s in Guatemala, walking from looking at the Banana Wars up to United Fruit invasion and coup, up to the 1980s, up until now.

And Nicaragua. It’s so shocking because of the fact that we walk from Walker to the longest US invasion in Latin American history in the ‘10s and the ‘20s and ‘30s. The creation of Sandino, and then freaking Somoza, and then finally it is just constant and continues. It is just mind boggling. It is shocking.

Alex Cox: And also Nicaragua didn’t really have… I mean, what did Nicaragua have? It didn’t have very much in the way of national resources, natural resources. But we just had to control that place. It’s like Walker says at the end of the thing: “It is our destiny to control you people.”

It’s not like it was Venezuela with enormous oil reserves, which the Rockefellers were always hovering around — And they owned most of the productive land in Venezuela at one point. It was just a small country which the United States and the Europeans have an obligation, or felt they had an obligation, to dominate.

And, of course, we see that now in Palestine. We see there exactly the same, but infinitely more hideous. The desire of the Western powers to support the white settler project of the Israelis and dominate the Palestinians, even if it means killing them all.

Michael Fox: Yeah, it’s just the same story over and over and over again.

Alex, how were you blacklisted in Hollywood? Because that comes because of Walker.

Alex Cox: The head of Universal Pictures was a guy called Tom Pollock, and he told my agent that I would never work in Hollywood again because of Walker. And he was right [laughs]! He was absolutely right. Because the studios operate as a cartel. Even though it’s illegal, they’ve been given this kind of bizarre exemption to operate as a cartel.

They don’t have unions, they have guilds, because the studios also control the guilds. And it’s a really bizarre and medieval-type situation, which benefits whoever benefits from what the Hollywood studios do. So if one studio blacklists you, they all blacklist you.

And then that spreads into the corporate world of Netflix, Amazon, Apple, because it’s all the same. It’s the same entity. It’s the same project. And it’s often the children of former asshole studio heads who become the heads of Apple or Amazon or Netflix. It’s a very, very small world in terms of the upper reaches of the oligarchy, whether it’s a film oligarchy or a political one.

Michael Fox: Unbelievable. I’m so sorry, Alex [crosstalk] that was a long time ago.

Alex Cox: Here’s the way it works. Because if I had had a proper Hollywood career, I would have had to be like Paul Verhoeven. Every film would have to be more expensive, because that’s how you are judged. You’re judged in Hollywood by how big is your house? How much money do you have? How much alimony are you paying? Let’s see your pool. All of this stuff. You have to live in Los Angeles, but you perhaps have a townhouse in New York as well. Who knows? And a place in Vale.

But none of those things interested me because I didn’t just want to go on spending more and more money and having less and less freedom of action. I always would have wanted to make the kind of films that interested me. So, whatever happened, I never would have found a home in Hollywood or in the mainstream film industry in the US or in Britain because they are so subordinated to… I guess we can say they’re so subordinated to the imperial project.

Michael Fox: At the end of the day, was it the politics of Walker? Was it the underlying message that they could not handle at Universal?

Alex Cox: I think it was the fact that we had gone to Nicaragua and we had spent more than $5 million worth of their money in that country supporting the Nicaraguan people and trying to present, while a very chaotic vision of Nicaragua, but also a vision of just how beautiful the place is and how the people are people just like us.

And there’s one guy, one of the actors in Walker, improvised a scene which we really didn’t write. And it was one of the crew, a guy called Roberto Lopez, and he was a Sandinista. He worked in some governmental activity down there. But he became one of our actors, and he said he wanted to have a scene where he explained the point of view of the contract.

And so there’s a scene in which, after the Battle of Rivas, this grieving former ally of Walker is staggering through the streets, shouting at his fellow countrymen for not understanding that the Americans who just provoked this terrible battle and brought cholera to the country have have come for our benefit: “Para fortalezer la economia”.

And it was a wonderful speech. It was a great idea because here was a guy who was a keen Sandinista, an enthusiastic, honorable Sandinista, who wanted to show in the film the perspective of the Contra, the perspective of a Nicaraguan who could turn against his country and support the Americans. He wanted to humanize and to explain that point of view. So wasn’t that interesting?

Michael Fox: That’s so profound, that’s so profound. What a moment.

Alex Cox: All the people we were working with, the Nicaraguans were poets. I would come into work and see one of the production coordinators and say, how you doing? I’m feeling a bit sad today because my friend was killed. But I’ve written a poem about it. Do you want to hear it? So it was really an experience unlike anything I’d had before.

Michael Fox: Was there an understanding on the ground in Nicaragua, by Nicaraguans or the people that you were working with, of the role of the US behind so much of what was happening in the 1980s, and propping up the Contras, and in training the Contras, and attacking with the CIA and whatnot?

Alex Cox: Oh yes, yeah. People in what we used to call the Third World are an awful lot more knowledgeable about politics and what goes on in the world than people in the US or Western Europe. We are now so thoroughly propagandized and the information that the mainstream provides is so limited and so twisted that inevitably you start talking to some poor person in Colombia or Venezuela and they’re going to have a much more sophisticated political appreciation than most people that you’ll meet in England.

Michael Fox: Absolutely.

Alex Cox: I shouldn’t say most people you’ll meet in England because if you go to the North of England, if you go to parts of England or Wales or Scotland where there isn’t a lot of money, people are much more politically conscious. It just depends on how big of a stake they have in the corrupt machine.

Michael Fox: That’s right. That’s right.

Alex, I was shocked when trying to find your movie to watch online. I couldn’t, and finally ended up buying a DVD and whatnot. But when Universal blacklisted you and pulled the movie — They pulled it, right? And up until how long ago was it that you couldn’t find it almost anywhere?

Alex Cox: I think the miracle was that I’d made another film for Universal called Repo Man, which they couldn’t understand at all, but it had been very popular and made a lot of money, and so they wanted to bring out this DVD. And they had some dolt who was going to do the DVD elements. And I said to this guy, I can’t work with you. You’re a fool. It wasn’t so rude, but I said I’m not going to work with this guy who doesn’t understand the film, doesn’t get it at all.

So then Universal came to me and said, as they had with the TV version, can you help us out here? So I said, OK, I’ll do you the DVD elements for Repo Man, but then you have to do something similar with Walker.

And the odd thing was they didn’t really honor that agreement. But because I delivered all the DVD elements for Repo Man and started bugging them, just to get me off their case, they gave the rights to Criterion.

But what they did with Criterion was they gave Criterion DVD and later Blu-ray rights, but they wouldn’t give them streaming rights. So that’s why you can’t stream Walker. Although I do hope that some criminal individuals have put it online anyway and that it’s available for download or streaming if you know where to look.

Michael Fox: I’m going to have to start looking better, I think.

Alex Cox: There’s a wonderful film called The Mattei Affair. Have you ever seen that?

Michael Fox: I haven’t, no.

Alex Cox: It’s by Francesco Rossi, the Italian director, and it is the story of Enrico Mattei, the father of the Italian petrochemical industry after the Second World War — Doesn’t that sound boring? But it’s one of the best films I’ve ever seen. It’s like a much more political Citizen Kane. And it stars Jan Maria Volante, a wonderful actor, as Mattei.

And the irony is no one may see this film anywhere in the world. This film is completely banned because it was made — Ironically, Rossi was a very political and brilliant filmmaker, all of whose work is available apart from Mattie — The film was funded by Paramount. And Paramount was, at that time, a branch of Gulf and Western, the oil company.

And one thing that Mattei does indicate is the complete corruption and villainy of the American oil companies, in no uncertain terms, going so far as to suggest that the oil companies may have murdered Mattei.

That film is completely unavailable legally. The only way you can see The Mattei Affair is via an illegal download or stream online. So go look for The Mattei Affair by Francesco Rossi, you can find it.

Michael Fox: Wow, Alex. It’s terrifying because we think of censorship as something that totalitarian governments do and whatnot. But then you don’t even think that large production companies, people like Paramount and Universal, are censoring their own work that they didn’t like. And yet it’s real.

Alex Cox: It’s not about making money for the corporation. It’s about safeguarding your position, rising through a hierarchy. And you only do that by not making waves, whether you’re a creative or an administrator, and by hoeing whatever row you’re supposed to be hoeing. So right now it’s let’s knit woolen socks for the poor Ukrainians, and then tomorrow it’ll be battle-weary Israelis need your help. But there’s always a new cause for those who wish to remain within the apparatus.

Michael Fox: Wow, Alex. I have one more question, and I just want to say thank you so much for everything. This has been such a pleasure.

Joe Strummer’s soundtrack is just stunning. I love it. When you were doing this, did you say, I know who’s gonna do the soundtrack of this? Or did you think about other options before?

Alex Cox: No. He knew who was gonna do the soundtrack. I didn’t know. I thought it was gonna be like a mixture of different bands and different composers and stuff like the previous films that I had done. And after we finished shooting, Joe came up with this idea that we should edit the film in Nicaragua. I thought, that’s a great idea. Let’s do it, man.

And, I said, listen, let’s get in the car and we’ll go to Managua, and we’ll meet this guy — Famous composer who wrote many revolutionary songs for the Nicaraguans, and we’re going to ask him to write a song for for the film.

And Joe goes, yeah, well, you know, I’ve been thinking about that, and I’ve been thinking, you know like your other films, you’ve got a whole mixture of different people writing music? But wouldn’t it be more interesting maybe if you just have one person write the music this time?

And I said, maybe. Who would that person be?

And so he stayed for two months while we were editing. He stayed in Granada in another house.

We would get together most evenings and watch videos. We only had two videos. In my house in Granada, we had a video of Ram by Akira Kurosawa, and we had a video of Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid by Sam Peckinpah, which Rudy had written.

And so we would just sit there, and it would be raining, that rain would be coming down on the patio, and we’d be sitting there by the VHS, and we’d watch Kurosawa, or we’d watch Peckinpah. He would bring by, on a little cassette, tapes that he’d recorded with samples of what the music might be.

And so Joe knew exactly what he was doing. He was very, very smart, and I think that he was inspired by what Dylan did for Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid. But I think, in a way, he even surpassed that because there’s so much. There’s only a couple of songs in Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid, whereas Joe wrote so much music for Walker. It’s a wonderful soundtrack. We’re very lucky.

Michael Fox: Amazing. Alex, is there anything else that you think is important for people to understand about Walker today, looking back?

Alex Cox: No. I think that what’s good is what you said in your previous podcast. I think it’s very important that people know about Walker, that he, as Vanderbilt said in Rudy’s script, “No one will remember Walker. No one remembers men who lose.”

But we have to remember men who lose or else we’re going to be endlessly making the same mistakes as they did. So I just want to say thank you to you for that podcast, and the opportunity to listen to the National Youth Youth Orchestra of Nicaragua rehearsing in Rivas. That was great.

Michael Fox: My pleasure, Alex, my pleasure. Listen, this has been such a pleasure. Thank you so much. I really, really, really appreciate it. And good luck with everything. Good luck with everything.

Alex Cox: Thank you, and you too. Good, safe travels, and good luck with the project.

[INTERVIEW ENDS]

[Under the Shadow theme music]

Michael Fox: That is all for this special episode of Under the Shadow.

Next time, as promised, we go to Costa Rica —

[Excerpt from episode] Because it was at this very site that the then-president symbolically knocked off a chip of the barracks, and he declared the end of the Costa Rican army, the military.

— To a country without a standing army. To the attempts for peace in the region and the US attempts to undermine the movement for change in Central America, even there.

That is next on Under the Shadow.

Just a couple of final things to say before I go. I’ve placed links in the show notes for Alex Cox’s work, Joe Strummer’s soundtrack for the movie Walker, and where to find the DVD.

If you are interested in checking out my new podcast, Panamerican Dispatch, you can find that at Patreon.com/mfox.

As always, the theme music for Under the Shadow is by my band, Monte Perdido. As I mentioned last time, we have just released a new album. Please check it out. And if you like it, share it with a friend. I’ve also linked to that in the show notes.

Under the Shadow is a co-production in partnership with The Real News and NACLA.

This is Michael Fox. Many thanks.

See you next time…