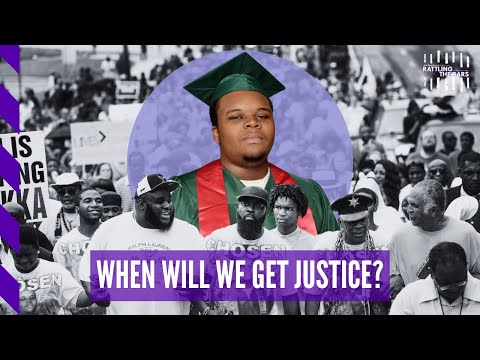

On Aug. 9, 2014, Officer Darren Wilson shot and killed Michael Brown in Ferguson, MO. Police left Brown’s lifeless body in the hot sun for four hours, plainly demonstrating the contempt of law enforcement for the local community. The righteous rebellion that followed in Ferguson shook the nation and the world, turning the Black Lives Matter movement that had begun following the earlier murder of Trayvon Martin into a global mass movement. Ten years later, some things have changed, but most things have not. Reforms have been passed at various levels concerning the power and accountability of the police. Yet the culture of impunity and the reality of racialized police violence as a daily occurrence in the US continues. In this special episode of Rattling the Bars, Taya Graham and Stephen Janis of Police Accountability Report join Mansa Musa for a look back on the past decade of attempts to stop police violence, and a discussion on why justice for Michael Brown and so many others continues to elude us.

Studio / Post-Production: Cameron Granadino

Audio Post-Production: Alina Nehlich

Transcript

The following is a rushed transcript and may contain errors. A proofread version will be made available as soon as possible.

Mansa Musa:

Welcome to this edition of Rattling Bars. I’m your host, Mansa Musa. We’re in a period of Olympics. If we was to deal with the Olympic analysis of my guests today and we had an event, the event would be watching the police run around the track and see who cheat and get a medal for exposing them. That would be the medal we would get, the medal for exposing police corruption and police brutality and fascism as it relates to the police department. Here, welcome Jan and Taya of the police accountability.

Stephen Janis:

Thank you.

Mansa Musa:

They’re on the dream team at The Real News Network, and I’m honored to have y’all here. When we was talking about doing something about Michael Brown and I said, “Yeah, it’s Michael Brown’s anniversary,” and we was talking about it. I said, “Maybe we can get Jan and Taya to come in,” because it’s like the highlight of my doing this is working with y’all and talking to y’all because y’all-

Stephen Janis:

Thank you.

Taya Graham:

Thank you.

Stephen Janis:

Thank you.

Mansa Musa:

One, y’all got depth. Now, y’all real cool people.

Stephen Janis:

Thank you.

Taya Graham:

Thank you.

Stephen Janis:

Well, thank you.

Taya Graham:

[inaudible 00:01:18].

Mansa Musa:

Let’s start. This is the 10th year anniversary of Michael Brown.

Taya Graham:

Yes.

Mansa Musa:

All right. We know that what came out of Michael Brown was a civil upheaval of demonstrations all around the country and all around the world.

Stephen Janis:

True.

Mansa Musa:

But more importantly, the way it was looking in Washington, DC, and the way it was looking in the United States, the fact that it was consistent and it was long. People came out, and people made it known that they was tired of police running them up.

All right. Let’s talk about where was y’all at and how did y’all cover that?

Stephen Janis:

Yeah. Well, it’s interesting because I was still part of the mainstream media sort of, as you know, at a mainstream media television, actually Sinclair Broadcasting, when the uprising around Michael Brown. So I wasn’t able to cover it, but we did end up starting to work here, both of us, when Freddie Gray died in police custody. So we were thinking about it because you had mentioned to us you wanted to talk about how things had evolved over 10 years.

One of the things that we both thought about when we discussed it was there has been, since Michael Brown and since the subsequent George Floyd and Freddie Gray, there has been tremendous amount of reform on the civilian side. In other words, even in Maryland for example, you used to have the Law Enforcement Officers’ Bill of Rights, which give police special privileges in the legal system when they do something wrong. That was repealed. So there have been things that have happened.

We have a consent decree in Baltimore. Many things that have happened. But I think on the side of policing, in terms of the culture of policing, I don’t think that has changed as rapidly as the civilian side of expectations. In other words, for a long time, the idea of police brutality was buried and not covered. I know, as a reporter when I covered it in the aughts, it was just my word against the police. Now that there had been body camera and things and there’s evidence, and Taya will talk about that in some specific cases, that makes a different type of way to process it and to push back against it.

However, I think still at this point in the actual bastion of policing, I think some of the same attitudes that create the sort of horrible situations we witnessed still persist. I think police are still trained to be very violent, to be very suspicious, especially with people of color, and to act out violently, preemptively, not as a last resort. Or I don’t think any of this talk about being able to deescalate, I don’t think that’s true.

In fact, there was just an article written by Samantha Simon in The Atlantic where she went to four different police academy trainings and what she talked about was how the police were trained to view us, and I mean the people-

Mansa Musa:

People, right.

Stephen Janis:

… as violent, possible murderers at any second and how that has persisted. So I think one of the things Taya and I talked about was you can’t say there have not been attempts and there have not been some real substantive changes. But I think police are still in this back and forth war with us that has been precipitated by the culture of policing.

Mansa Musa:

Before I go to you, Taya, let’s talk about a point you made, and I think our audience need to really understand this, is the fact that there has been some changes on the civil side. That’s the society looking for a place where the police represent their motto, serve and protect.

Stephen Janis:

Exactly.

Mansa Musa:

With the culture being what it is, how do we make inroads into that?

Stephen Janis:

I mean I think that’s very difficult because, so for example, Taya and I attended the Republican National Convention, and there was a sign, Back the Blue. The conventioneers were touting these signs, I think, because police have become a part of the political process. I mean one of the things in this country, we try to separate the military from politics because we know that people with guns and badges enforcing political ideologies can be an extremely fraught authoritarian experience.

But when you’re down in the convention, you turn around and you see all these signs, Back the Blue, it just makes policing feel like it’s in a different realm than where it really should be, which is municipal service. I think that’s a political battle, unfortunately, that is still being fought because Republicans are using it as a kind of wedge issue. You still hear this silly, and I would say extremely silly, Defund the Police mantra, which anyone who knows anything about municipal budgeting, covered cities and policing, police departments have excess funding many times.

You still hear this. They’re still throwing out, “Well, you said, ‘Defund the police,’ without ever thinking about can a municipal agency be held accountable?” So the problem is that it’s become so political that I think it’s going to be hard to change that culture because the police see the support from the right side, from our more authoritarian side, and they say, “Well, we need to just embrace this and ratchet up, and we don’t need to respond to what the civilian side wants.” So I think it’s going to be very difficult.

Mansa Musa:

Tay? Go ahead.

Taya Graham:

Can I add to that? Because you brought up something really interesting in relation to the way policing is politicized, and it’s something that we always joke. So if somebody from the DPW was supposed to-

Stephen Janis:

The Department of Public works.

Taya Graham:

… for the Department of Public Works was supposed to recycle and instead of recycling, they took all our recycling and just dumped it somewhere, would we be wrong to criticize them? Would we be attacking the very fabric of society to say, “Hey, they’re supposed to do their job this way and they didn’t?” No, of course not. That person who took all our recycling and did whatever they wanted with it would probably get reprimanded, if not fired.

But if we say, “Hey, Baltimore City Police Department has been shooting unarmed people. We have a problem with it,” suddenly, the politics are involved. Suddenly, we are anti-American. Suddenly, we’re not being patriotic. We’re not supporting our boys in blue. Well, wait a second. They are paid by us, the taxpayers. They are supposed to protect and serve. That police culture that we’re talking about, unfortunately, really hasn’t changed.

I think we have some really strong signs of that. I mean I think what we covered with Sergeant Ethan Newberg, that’s a Baltimore City police officer, one who was making $239,000 a year-

Mansa Musa:

Right. Of taxpayers’ money.

Taya Graham:

… of taxpayer dollars. But thanks to this body-worn camera program that was started in SAO Mosby’s office, they were reviewing the body camera video. They looked at about six months’ worth of it, just six months, and they found nine occasions in which he committed 32 counts of misconduct in office, 32 counts, just nine occasions in six months. Can you imagine what that man was doing before there was a body-worn camera program?

Mansa Musa:

That’s right. Yeah, yeah.

Taya Graham:

Can you imagine all of the crimes he committed against our community that we don’t even know about? Guess how much time he spent in jail?

Mansa Musa:

How much?

Stephen Janis:

Six months?

Taya Graham:

No, no. He got six months probation that he could spend at home.

Stephen Janis:

Home detention.

Taya Graham:

Home detention.

Mansa Musa:

Home detention.

Taya Graham:

Home detention. He didn’t even spend a night in jail for terrorizing our community-

Stephen Janis:

I mean it’s really kind of-

Mansa Musa:

Yeah, exactly.

Stephen Janis:

It’s really kind of interesting because I was just looking at the community report. There’s a report, State Senator Jill Carter passed a law that required a certain type of reporting mechanisms for the police department. What’s really interesting about it is right now the Baltimore Police Department in the latest survey has about 2,100 sworn officers, which is about 700 or 800 officers short of their capacity and what they normally are staffed at.

However, we are in a year of record … We probably will have a record low homicide rate, and we did last year under the kind of circumstances where there’s low police staffing. So what does that tell you? That tells you that this idea of this equation that underlies the whole political argument of police-

Mansa Musa:

Come on.

Stephen Janis:

… that more police make us safer is absolutely false. But it doesn’t really get into the political equation. Now, in Baltimore, people had a choice. They could have elected Sheila Dixon, who was more the pro-police, or they could have gone with Brandon Scott, who had a more … What was it called? GVSR? A gun-

Taya Graham:

Oh, it was a gun violence reduction safety-

Stephen Janis:

Which was a complete community program, which is what he created with this. They chose the community program because we’ve seen this up close. But really, I think on the broader scale of American politics, this hasn’t been digested by people that, you know what, your main argument for more police and giving police the powers to do things that are unconstitutional is that we’ll be safer. There’s no proof of it, and Baltimore is an perfect exemplar of the fact that that’s just not true.

We have less police and less crime. So to the police partisans, I say, “Explain that to me. Why has that happened?”

Taya Graham:

Exactly.

Stephen Janis:

So it’s just a very interesting dynamic because it-

Mansa Musa:

Really, the issue it underlies is this, is that, one, the police never have been put together as representative of the community. So that’s the beginning. There’s always been there to serve and protect the property interest of corporate America and capitalists. Here we come along and we say, “Okay, but that’s not what your mandate say. That’s not what your oath say.” So we try to hold you accountable to the things that you’re supposed to be doing.

Let’s walk back. So we had Rodney King. The response to Rodney King was a spontaneous Riot, looting, killing, whatever. That was the response because of what people seen, the visual aid of what people seen-

Stephen Janis:

Yes. Absolutely.

Mansa Musa:

… more importantly, and it was in California. They showed you how the relationship between the police and Californians. They acquitted OJ because they said the police. When they interjected the police in this case, it don’t make no difference what you did, in their mind, we got empirical evidence and examples of the police being bad. So can’t nobody be worser than them in the situation. All right. All right. We got Trayvon Martin. Then we got-

Stephen Janis:

Michael Brown.

Mansa Musa:

Michael Brown. Then we get Freddie Gray-

Stephen Janis:

Freddie Gray.

Taya Graham:

Eric Garner.

Stephen Janis:

Eric Garner.

Mansa Musa:

Right. Eric Garner, Freddie Gray, and then George Floyd. Not talking about what’s happening in between that.

Stephen Janis:

Because there are a lot of cases on top of that.

Mansa Musa:

Right.

Taya Graham:

Sandra Bland-

Stephen Janis:

Sandra Bland.

Taya Graham:

… in 2015, all of that recorded by the dash camera. It was absolutely heart-breaking.

Mansa Musa:

And in each case, the cry from the public and the masses has been, “Change the police,” whatever we say that is. We Come up with terminology like defund, when we saying defund, better training. We come up with a whole host of things that we want to see done around the police, and the system and the capitalist response is, okay, we’re going to take what you say and we’re going to interpret it the way that advances our narrative-

Taya Graham:

Absolutely.

Mansa Musa:

… ergo Cop City. They saying what they offering in Cop City is that, “Oh, we’re training police to better serve and protect.” Okay. But going back to your point, Jan, why do you need military-style training? Why do you-

Stephen Janis:

Right. Well, you know-

Mansa Musa:

Go ahead.

Stephen Janis:

One thing that Taya and I always not laugh about, but we covered very extensively the consent decree between the Baltimore City Police Department and the Department of Justice, which was the result of the uprising after Freddie Gray. But what was amazing about it is we both looked at each other and they announced $70 million in new funding for the police department.

So the police department literally wreaks havoc in the community, creates the conditions in which people felt the need to literally rise up, and their response was, “Let’s give police more money and training.” Right, Taya?

Mansa Musa:

Money.

Taya Graham:

Absolutely. You know what? When you brought up Cop City, you took the thought right out of my mind because when you said capitalism, you said policing, and you said, “What is the real comparative policing?” The Cop City that they want to create, guess who’s funding it?

Stephen Janis:

Yeah. Corporations.

Taya Graham:

Coca-Cola, Home Depot, Wells Fargo.

Stephen Janis:

Private companies. The Atlanta Police Foundation.

Taya Graham:

I mean if this doesn’t show you the tie between capitalism, the protection of property, and what police are really there to do, I don’t know what will.

Stephen Janis:

Yeah. So it always is, in these situations, more money doesn’t flow to the community, even though community programs are shown to be really more effective. Instead, more money flows to police. No matter what happens, it’s like heads, I win, tails, you lose. The more money comes to them in the form of this police reform infrastructure you’re talking about. It becomes almost a business opportunity-

Mansa Musa:

It is.

Stephen Janis:

… because there’s just so much money available to people who will say, “Oh, I can help reform the police.” I forget the police, the thing that there’s-

Taya Graham:

Like the ROCA?

Stephen Janis:

Yeah, ROCA. Not ROCA per se, but there’s just so many organizations and people who can take advantage of the funding that flows to policing. Go ahead.

Mansa Musa:

And the Fraternal Order of Police in everywhere, they’re like a lobby beyond a lobby because-

Taya Graham:

Because they have the power.

Mansa Musa:

… no matter what goes on, they always going to paint the narrative that we’re here to serve and protect, and you taking our ability to do that. Bump the fact that we’re killing people indiscriminate. Bump the fact that we fabricating cases against. Bump the fact that we taking and manufacturing evidence against people or like in the case that you talk about all the misconduct.

The connection is that you’re doing this with impunity. So you can take and say, “Oh, well, I’m going to cook the books or I’m going to misappropriate money and I’m doing it with impunity. But in the interim of me doing that, I was out on the street shaking down people. I got numerous of people arrested. I locked up and swore an oath that what I say they did, they did, and you take me at my word because I’m the police.” But the person that’s the real victim of it is the person that you supposed to serve and protect.

But let’s talk about the reactions from each one of these periods because, like I said, in the era of King, the beating, it was rioters. People literally was outraged because of what they seen, and it was more the visual than anything else and what they seen. And then when you had Trayvon and you had the other one, you didn’t have as much of a reaction in terms of when you got to Michael Brown. Why do you think that Michael Brown had that type of impact?

Stephen Janis:

Well, I think because I just saw from a reporter covering police brutality prior to the cell phone camera and the visuals that you would see, that it was very difficult sometimes. You’d write about really what you knew were horrible police shootings where someone would get shot in the back and you just knew it was wrong, but you didn’t have visuals.

I think in the case of Freddie Gray, you saw Freddie Gray being taken into the van. Michael Brown, you saw his body lying on-

Mansa Musa:

Just laying out there.

Stephen Janis:

Eric Garner, you saw him being in the chokehold.

Taya Graham:

Being put in that chokehold, all those officers on top of him.

Stephen Janis:

I honestly think it’s like the civil rights movement of the ’60s where-

Mansa Musa:

Right. Edmund Pettus Bridge.

Stephen Janis:

… video finally could show people and when people could finally see it, even if it wasn’t always directly what happened. I mean everyone saw Freddie Gray being put in the van on the second stop when he was hogtied. I’d say he was hogtied with handcuffs and thrown into the back like a piece of trash. And then he ended up hitting his head, but whatever. Everyone could see that. When you can see it, I think it has a bigger effect. The cell phone cameras were instrumental just as much as a body camera.

Taya Graham:

Absolutely. Cell phone cameras, CCTV footage, and now finally, body-worn camera are one of the most important tools that this civil rights movement has because just like you were talking about the Fraternal Order of Police, they’re often arguing, “The Constitution is getting in the way of our cops doing good policing. It’s getting in the way of it.”

Mansa Musa:

That’s an oxymoron.

Stephen Janis:

Yeah.

Taya Graham:

It’s ironic, that idea, well, you’re going to have to bend or even break the law to be able to uphold it and be able to serve it. When you were talking about in Ferguson, I think that moment where you saw him. He had his hands up, and he said, “Don’t shoot.” We saw that he had nothing in either hand, and that officer still gunned him down anyway. I think the visual of that, the visual of seeing Eric Garner have six officers on him with one in a chokehold-

Mansa Musa:

Chokehold.

Taya Graham:

… and knowing that all he was doing was selling some loose cigarettes, and they’re on top of him like that. You could tell he’s a big man. He’s got breathing issues. You could tell that they were harming him. You could tell that. He’s saying, “I can’t breathe.” So I think seeing those moments on camera in the same way that you mentioned with the ’60s civil rights movement, I think it’s when those images from Vietnam came home-

Mansa Musa:

That’s right.

Taya Graham:

… and they saw little children being harmed, being devastated by war, when they saw those images, that really helped motivate people in the same way. Seeing those images of African Americans being unarmed and being harmed and gunned down, people really started to understand that what we had been saying all along was true, that these officers were killing our people.

Stephen Janis:

To your point, I mean the one case that really influenced Maryland’s legislation, where most of the legislative action was not actually Freddie Gray, but George Floyd, because, visually speaking, George Floyd was so direct and graphic and so unambiguous. I mean it ended up actually exposing our corrupt medical examiner ruling in favor of police, Dr. David Fowler, because he ended up testifying that George Floyd did not die from positional asphyxiation, but rather the tailpipe that was next to him.

Taya Graham:

Yes, it was carbon monoxide. This is what our medical examiner-

Stephen Janis:

Yeah, who had been ruling controversial.

Taya Graham:

… the medical examiner that we had over 20 years, the one we had here, the same one who ruled that the death of Tawanda Jones’ brother-

Stephen Janis:

Tyrone.

Taya Graham:

… Tyrone West was accidental and due to him having a heart condition. It had nothing to do with the police officers that body-slammed him on the ground.

Stephen Janis:

And Anton Black.

Taya Graham:

The death of Anton Black down in Greensboro, Maryland, a 19-year-old young man that was a track star, and you can see in the body camera video, these big officers-

Stephen Janis:

Just sitting on top of him.

Taya Graham:

… sitting on top of him.

Stephen Janis:

Positional asphyxiation.

Taya Graham:

They said, “Oh, he died because he had a heart abnormality.” That’s the type of rulings that Dr. David Fowler gave.

Stephen Janis:

So-

Taya Graham:

So when he went in front of the entire country in that courtroom-

Stephen Janis:

And testified.

Taya Graham:

… and testified that it wasn’t positional asphyxiation, the police officers were not a contributing factor, that the fact that he had drugs in his system and that the car tailpipe was near him, that was most likely carbon monoxide poisoning that contributed to his death. Literally, over 400 Pathologists and medical examiners around the country said, “You need to audit this guy. You need to audit him.” They signed a petition.

Stephen Janis:

I guess my point was that George Floyd, I think, from our perspective of covering policing, had the greatest impact on legislation and just change. So that’s why I would say it’s the visual component that makes the difference.

Mansa Musa:

The thing about George Floyd, unlike the other ones, was like you said, the visual aid, but it went national and worldwide. But this was the issue with it. The only way you wasn’t affected by it, you ain’t had no conscience. I don’t care what station in life, where you at in your politics, I don’t care who you like, “Yeah, I’m all for Trump, but I can’t be for that,” because it was so graphic.

Stephen Janis:

Yes.

Mansa Musa:

That’s what caused the reaction because, in that reaction, and I want y’all to speak to this, in that reaction, you had the movement, Black Lives Matter. You had a more strategic push which led to legislation or led to people who was conscious trying to talk about this more so than anywhere else.

So why do you think that at this stage right now? We know we had that. We know we seen that. We know we seen the upheaval. But at this stage right now, the problem hasn’t changed.

Stephen Janis:

No.

Mansa Musa:

They just shot is boy in the back in Baltimore City. Go back to I think what you say, Taya, or you, Jan, where they say the training was to look at us as us as being-

Stephen Janis:

Yeah, you know-

Mansa Musa:

… look as that first. It ain’t a matter of me what I’m doing. It’s a matter of you in my view, running with your back away from me. But in my training say you a threat or I got to subdue you to stop you from being a potential threat, and the way I do that is I kill you.

Stephen Janis:

Yeah. I mean so there’s a couple things because, for example, just so people understand, despite all these reforms, in 2017, 981 civilians were shot and killed by police. In 2023, it was 1,161. So it has continued to increase, unfortunately. I think what we have to understand, there’s this idea that Taya and I wrestle with all the time about police corruption because the idea being that there’s this police force that if you just reform them to a certain extent, they will suddenly be good or whatever.

But I think what’s more important to understand is that policing just reflects the underlying problems with the society that it purports to serve. In other words, Baltimore City, the way Baltimore City’s economically and racially constituted, the way Baltimore City violated the rights of African Americans, all those things were reflected in the policing. So unless you reform society’s corrupt … As you pointed out, the idea that property is more important than human life-

Mansa Musa:

Right, than human life, really.

Stephen Janis:

Unless you reform those elements, policing is always going to be responsive to the power and the corrupt power of the society in which it is situated. So I think that’s what is very difficult about this reform problem because you really can’t just say you’re going to be able to, in isolation, reform police.

If the society or the city or the county or the country in which this policing is situated is not reformed first, I think policing will continue to be memetically reflecting what is going on in that society. What perverse incentives there are, what racial problems there are will always be reflected in policing.

Taya Graham:

This conversation’s got me thinking about so many different things. We’re talking about these lethal uses of force, and I was thinking of Sonya Massey, 36-year-old woman, Springfield, Illinois.

Mansa Musa:

Come on now. Come on. Come on.

Taya Graham:

You see her. She calls police because she believes there’s been an intruder around her home. She calls 911 for help. Officers go take a look around. They see a car that’s had its windows broken into. So perhaps she was right. Perhaps there had been an intruder around her home. She comes to the door, and she’s just wearing a bathrobe. You can tell that she has no armaments on her whatsoever. The officer goes very close to her and speaks to her, but then insists that he needs to see a form of ID. So that’s when she’s like, “Well, I have to go in the house and look for it.”

When we get to the point where he says to her, “Turn that pot of hot water off. I don’t want a fire,” she says, “Okay.” She goes over there. Until that moment, they had been somewhat laughing and joking together. She goes over there, and she makes a comment. He’s like, “Get that hot water.” She’s like, “Oh, I rebuke you in the name of Jesus.” And he’s like, “I will shoot you. I shoot you in your effing face,” and he immediately pulls the gun up.

I reported on this, and I had people say, “Well, it’s possible she threw that water in his direction.” I was looking at the distance. There was a counter between her and them. I was like, “No one said, at any point, they could have left. They could have backed away.” What happened to de-escalation?

Mansa Musa:

Yeah. What happened to all that? Yeah, what happened to all that? Yeah.

Taya Graham:

Although personally, from what I saw of the body camera video, I do not believe at any point she was genuinely threatening either one of those officers with that pot of hot water, if they truly believed that what was occurring, they should have retreated. There was no reason to shoot an unarmed woman in her face three times and then not give medical aid. It’s absolutely incredible.

Mansa Musa:

See, that go back to something you said earlier is they’re being trained to be assassins. They’re occupying forces in our community. They’re being trained. De-escalation is like a no de-escalation in their mind is problematic for them because I can gain control by de-escalating, but that’s not control for them. Control for them is I kill somebody and the threat of me will shoot you and kill you. It’ll help you de-escalate, get out my face. Because, like you say with Sonya Massey, it was no threat there.

When you running away from the police, when you running away, it’s only in the movie where somebody running from the police and shooting back like this here and the police get hit. That’s only in the movie. I don’t care what you got. When you run away from the police, the very act of running away is saying I’m trying to get away. So, in your mind, what do that mean? That mean that you’re trying to, what, hurt me?

But let’s talk about the reforms and how they’re not being implemented or how they’re being played because we know right now, the George Floyd Bill hasn’t been passed.

Stephen Janis:

Right. The George Floyd Act, yes, it has not.

Mansa Musa:

George Floyd Act. Every time something come up with the woman, Sonya Massey, “Oh, look, we need to sign the George Floyd.”

Taya Graham:

Oh, that bill died in 2021. It died in Congress. You know what? That bill was so reasonable. They’re saying, “Hey, let’s codify that there should be no chokeholds. Hey, let’s codify that there shouldn’t be no-knock warrants. Hey, you know what? Let’s stop the 1033 Program and stop giving small-town police officers BearCats and literal tanks to police their communities with.” There was not a thing in there that would be considered radical, just some really reasonable reforms, and it died.

So with all the public outcry, with all the pressure, the organizing, the activism, and like you said, we have the body camera that shows exactly what happened, they still couldn’t get that bill passed.

Stephen Janis:

One program that strikes me as very interesting that it’s worth thinking about in the context of this discussion is the Safe Streets Program in Baltimore because I’ve watched it evolve from having absolutely no dedicated funding to growing and getting some state-dedicated funding. But throughout that process, there’s been this pushback from police partisans specifically through our local Sinclair Broadcasting affiliate, which has continually questioned and continually pushed back and questioned the spending, which is minuscule compared to the police department.

But the main component that I think that the police partisans don’t like and is revealing, I think is the fact that Safe Streets is not an armed force. It is supposed to be de-escalation. It is people in the community who are trained and who have knowledge of the community to simply de-escalate, not shoot anybody, not put anybody in handcuffs. It’s really supposed to be a community mediation program.

I don’t know how you feel about it, but with the people that I interviewed who participated in the program struck me as extremely courageous and dealing with very difficult circumstances, and I thought it was really interesting that a program that was really saying, “We don’t need guns and badges and arrests. We need members of the community who are empowered to mediate,” I always thought it was interesting that places like FOX45, Sinclair, the people who have been very police-focused, found it to be threatening. What is threatening about mediation exactly?

Mansa Musa:

The person that started it, Leon Faruq, we was locked up together. When he got out, he created that concept-

Stephen Janis:

That’s amazing.

Mansa Musa:

… for the purpose of making the community safe and educating the community how to interact with the police, and more importantly, to get the police involved in the community and understanding the community. So what they did over the years, like you said, you get this pushback, and then you vilify some of the people that’s in it.

Stephen Janis:

You vilify people. They definitely did that.

Mansa Musa:

So now you’re saying you shift the focus off of the work that they’re to the individuals that’s involved in the group. But going forward, how do y’all see this playing out in terms of because we know that right now it’s shifting? I know in DC, when they passed their last bill, Safe Street or whatever, she put in there about chokeholds. They passed a policy about you can choke them, but you just can’t put this on them. You can put this on them.

It’s a different hand gesture. You can’t choke them with an L, just choke them with both of your hands, and it’s not lethal. But I guarantee you when you look back over all these cities that, mainly with the uptick of what they call crime, that they have went back and undid a lot of the common sense reforms.

Stephen Janis:

I agree. But I mean I think there needs to be a reckoning with what is evolving in Baltimore where you have a large reduction in violent crime, like police shootings and homicides, and yet you have fewer and fewer police. We, as media, need to force people to reconcile with that, to answer the questions about that because the narrative that has driven the excesses and abuse of police that we have seen is the narrative that more policing somehow means more safety or, as Taya mentioned, allowing police to ignore constitutional rights. Or constitutional rights are a barrier to good policing and safety and all these things.

All these things are absolutely hinged upon the fact that somehow unleashing a militarized force in a civilian society can somehow make it safer. We, as media, have to really, really push that question and question that underlying assumption. It is so important, and it really frustrates me because no one’s asked that question. It’s right there in black and white. The Baltimore Police Department is staffed at historically low levels. Why are homicides going down?

Well, it’s because Mayor Scott, and I’ll give him credit for that, invested in community-oriented violence intervention programs, not because of the police. If we can dislodge policing from that idea that somehow they’re the barrier between civilization and chaos, I think we’ll go a long way to getting real police reform.

Mansa Musa:

Yeah, I agree. Taya?

Taya Graham:

But the other part of the discussion about how media should handle this is that when we report on police misconduct, we can’t have the public or the government come out to kill the messenger.

Stephen Janis:

That’s a good point.

Taya Graham:

The example I would want to give of that is when we were covering Sergeant Ethan Newberg. He’s the officer I mentioned earlier, making over a quarter million dollars a year for literally terrorizing our community. We sat in that courtroom and watched him read, I would say, what was a less than heartfelt apology to the victims of his criminal misconduct against them. During that speech, he was looking over at us, and he mentioned, “I don’t think I would be standing here today if it wasn’t for certain members of social media.” He looked over at us a couple times.

Stephen said, “He’s looking at us.” And I’m like, “No, he’s not. You’re just being paranoid.” He’s like, “No, he’s looking at us.” After he was told that he was going to get just six months home detention, another reporter came up to us and was like, “Well, what did you do? Kick his dog? Why did he keep looking at you like that?” The thing I realized is that he blamed us. It was our coverage that put him in that position, not his unconstitutional behavior.

Stephen Janis:

That’s a good point.

Taya Graham:

There are members of the public that feel that way, that if we highlight a police officer doing harm against the community, that we’re creating a problem. No, it’s the officers who are breaking the law-

Mansa Musa:

The law, yeah.

Taya Graham:

… who are harming the community that are causing the problem. So that’s the other thing that when you are a member of the media and you do step out and you do say the truth and you speak it out and you show the body camera footage and you give the victim side of the story, people turn on us and say, “You’re making it worse.” We’re saying, “No, you guys need to clean this up.”

Mansa Musa:

As we close out, y’all got the last word. We’ll start with you, Jan.

Stephen Janis:

Well, no, I mean, again, I think police reform will not really occur unless you see fundamental shifts in the way we discuss things like violence and poverty and unless we address those underlying issues. Police is a really simple solution for late-stage capitalism to suppress people’s political efficacy and suppress their ability to say, “This is wrong. I shouldn’t be going broke because I can’t pay my medical bills.” All those things are intertwined.

I think if we recognize that, that is where the real reform will occur. Recognizing police role that we talk about a lot in our show in the inequality equation and enforcing racial boundaries, that has to be discussed and fleshed out in order for real reform to occur.

Taya Graham:

The only thing I would add to that is the fact that the culture of policing is a serious problem. And it’s not just Dave Grossman’s Warrior Cop training or his Killology training or the New Jersey Street Cop training, which I would suggest anyone look up what those events look like. That Street Cop training was absolutely insane. You can understand why police would go out and just be terrible to the community after attending an event like that.

But that the culture of policing, I think the best way to think of it is what we saw with George Floyd, that veteran officer kneeling on Floyd’s neck and the two other officers just going along with it, just going along with it, not one of them spoke up and said, “Well, maybe we should render some aid now. Maybe we should stop.” They went along with it.

So as long as the veteran cops keep on replicating this unconstitutional, to say the least, style of policing, we’re going to continue to get it. So we have to attack the heart of this police culture or we will continue to get the same results.

Mansa Musa:

There you have it, Rattling the Bars, Real News. We have to attack the culture. As Jan said, you have low homicide incidents in Baltimore City and a low police force. That mean that whatever the alternatives they’re doing, they’re working in terms of making the community safe. So why are we not investing in that? Or why do we continue to invest in a police force as an occupying force in our community? We need to ask these questions.

As this is the 10th year anniversary of Michael Brown, we recognize that some changes have been made, but more importantly, the biggest change that’s being made is the consciousness of the community and people becoming more and more aware of police. This is because of people like Taya and Jan and the Police Accountability Report. Thank y’all for-

Taya Graham:

Thank you so much for having us.

Stephen Janis:

Thanks for having me. It was great.

Taya Graham:

We really appreciate it.

Stephen Janis:

For having us.