When it comes to putting a price tag on Baltimore’s expansive list of tax incentives for developers, even a simple request for financial data can lead to complicated answers. City officials learned this the hard way when they asked the Maryland Department of Environment (MDE) for data on what was being spent on cleaning up contaminated sites that have earned a lucrative tax break known as a Brownfields tax credit.

Instead of sharing the data, the MDE forced the city to file a Maryland Public Information Act request in order to access it. The request also prompted state officials to reveal that the program is not required to track remediation costs for these cleanups.

“The Land Restoration Program has repeatedly informed the city that we do not have costs of remediation for projects,” MDE spokesman Jay Apperson told TRNN when asked why the city had to file an MPIA request. “MDE’s Land Restoration Program’s responsibility is to review the assessment and remediation of sites. The program neither asks for nor is provided with cost information for remediation.”

The revelation that the state does not tabulate what property owners are spending to clean up contaminated sites comes as city officials have expressed frustration with the increasingly costly tax credit. Baltimore grants roughly $20 million annually to developers who qualify for the credit, and the city must also pay into a state program that funds remediation across Maryland. However, finance officials have little control over who receives the credit and how much the incentive benefits Baltimore in return.

Concerns over the rising cost of the credit and how it was being used by developers was the subject of an internal memo circulated among the top staff of Mayor Brandon Scott’s administration in 2021.

“According to conversations with BDC, most of the City can technically qualify as a brownfield due to small traces of toxic material that can be found in soils from prior industrial uses. As such, the State does not designate individual parcels as brownfields before development begins,” the memo outlines.

“Instead, builders eye land that is ripe for development, and then get the parcel certified as a brownfield site through MDE. This turns the intent of the program on its head. Instead of compensating builders for performing clean ups of known contaminated sites, it allows developers to purchase land and then perform the minimum cleanup effort in order to qualify for a generous credit,” the memo argued.

The increasing costs and lack of data on what’s being spent to reclaim contaminated property prompted the city to ask MDE for data. Apperson explained the city was asked to file a MPIA request — an unusual demand of a municipality seeking information — due to the breadth and scope of information the city asked the agency to provide. “The Land Restoration Program often provides information without a PIA request, however this request was large, for files — related to, initially, 14 sites, later about 28 sites — requiring time and resources,” Apperson wrote in an email to TRNN.

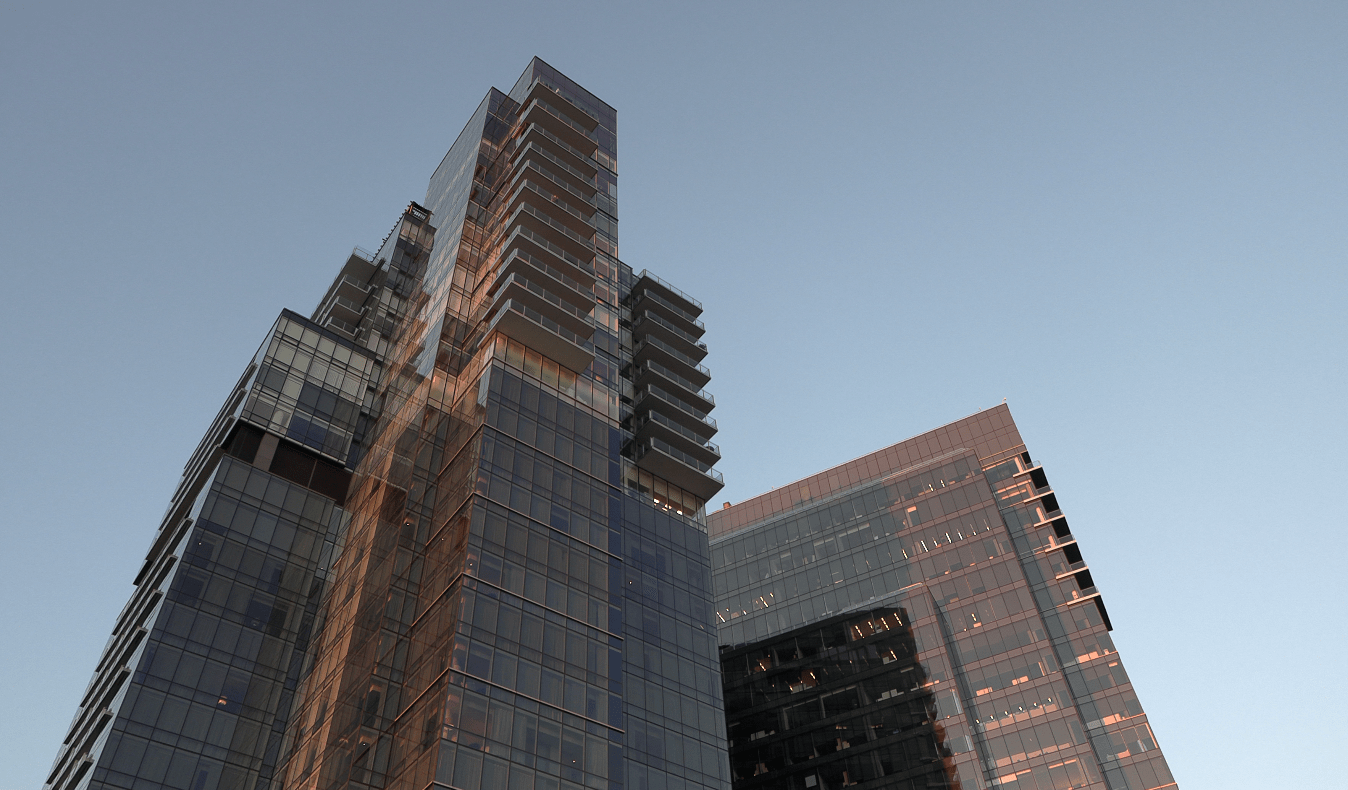

Questions of just how much the city benefits from the Brownfields tax credit was first highlighted by a TRNN report which revealed the state application for one of the most controversial recipients, the luxurious Four Seasons Hotel and condominiums, did not include costs for remediation. The application resulted in Brownfields credits worth roughly $10.5 million: $6.8 million for the condos atop the hotel and $3.4 million for the hotel itself. However, the application revealed that in 2007 the developer’s lawyer told state officials there was no contamination on the planned site of the building.

“Prior environmental evaluations, several rounds of sampling and analysis, and environmental monitoring during construction through late 2007, did not indicate environmental contamination within the site boundary,” the lawyer wrote in an affidavit. MDE officials said that construction can serve as remediation. For example, Apperson noted while building the Four Seasons parking garage traces of chromium were found in the water near a slurry wall. Thus building the wall itself would count as remediation, he said.

Recently the cost of Brownfields credits awarded to developers in Baltimore has exploded, rising roughly 154% over the past five years. The total cost to the city’s budget has more than doubled from $8 million annually in 2016 to $20 million in 2020, according to a report commissioned by the city to study tax breaks.

The program was authorized by the Maryland state legislature in 1997 to encourage developers to remediate property that was contaminated by past industrial use. It grants a 50% tax break for five years for certified properties, and 10 years if the project is located in an Enterprise Zone, another tax credit that incentivizes commercial development in impoverished neighborhoods.

The lack of transparency around the Brownfields tax credit is examined in “Tax Broke,” a broader TRNN investigation into Baltimore’s reliance on tax breaks to fuel development. The series includes a documentary outlining the history of the city’s struggle to grow, and how incentives created to attract residents and new development has led to burgeoning costs and little transparency on the final price tag or the performance of the projects financed with tax breaks.

The investigation found that the system for awarding tax incentives is plagued by lax transparency and little, if any, analysis on the performance of the projects that receive them. The cost of Baltimore’s tax credits and subsidies is now coming under new scrutiny as the city faces an unexpected increase in state requirements on spending for education. Under the Kirwan Blueprint for Education, a revised formula requires the city to spend an additional $79.4 million on local education for fiscal year 2024, six times more than expected. City officials have called the increased spending a “gut punch.”