The 1979 Nicaraguan revolution that overthrew a brutal U.S.-backed dictator ushered in a wave of hope in the Central American country. The new Sandinista government launched literacy and healthcare campaigns, carried out land reform and promised to improving the lives of all.

But the United States, under president Ronald Reagan, feared the dominos would fall across Central America, and they unleashed assault on the country: paramilitary war, CIA attacks, economic blockade, and much more.

In this episode, host Michael Fox, walks by into the 1980s, to the overthrow of dictator Anastasio Somoza and the beginning of both the Sandinista government and the U.S. response.

This is Part 1, of episode 10.

Under the Shadow is an investigative narrative podcast series that walks back in time, telling the story of the past by visiting momentous places in the present.

In each episode, host Michael Fox takes us to a location where something historic happened — a landmark of revolutionary struggle or foreign intervention. Today, it might look like a random street corner, a church, a mall, a monument, or a museum. But every place he takes us was once the site of history-making events that shook countries, impacted lives, and left deep marks on the world.

Hosted by Latin America-based journalist Michael Fox.

This podcast is produced in partnership between The Real News Network and NACLA.

Guests:

Alex Aviña

William Robinson

Marvin Ortega Rodriguez

Eline Van Ommen

Peter Kornbluh

Edited by Heather Gies.

Sound design by Gustavo Türck.

Theme music by Monte Perdido and Michael Fox

Other music from Blue Dot Sessions.

Additional links:

- Follow and support journalist Michael Fox or Under the Shadow at https://www.patreon.com/mfox. You can also see pictures and listen to full clips of Michael Fox’s music for this episode.

- Support Coletivo Catarse, the media collective Under the Shadow sound engineer Gustavo Türck belongs to. Coletivo Catarse is currently dealing with devastating floods that have hit the state of Rio Grande do Sul.

- Read Mike Fox’s recent coverage on the catastrophic flooding in Rio Grande do Sul from PRX and NACLA.

- For Declassified documents on the U.S. contra war on Nicaragua, and Iran Contra, you can visit Peter Kornbluh’s National Security Archives here and here.

- Eline van Ommen’s book, Nicaragua Must Survive: Sandinista Revolutionary Diplomacy in the Global Cold War (University of California Press, 2023), is available here.

- For the 2007 documentary American Sandinista, you can visit the website of director Jason Blalock.

- Here are links to the 1980 documentaries about Nicaragua’s literacy campaign that I mention in this episode: La Salida & La Llegada

Transcript

Michael Fox: Hi. I’m your host, Michael Fox.

You may have noticed that we are a week late releasing this episode. I apologize. We were slowed down by the heavy flooding in Southern Brazil — They’re actually calling it Brazil’s Katrina. More than 600,000 people have been pushed from their homes. And our incredible sound engineer Gustavo Türck, and the collective he works with Catarse, are in the thick of it in Porto Alegre. I’ll add links to their work and some recent reporting of mine on the floods in the show notes.

Before we get started, I want to say a few more things. First, like Episode 7, about the 2009 Honduran coup, we have also decided to split today’s episode into two parts. Today we’ll look at the 1979 Nicaraguan revolution against dictator Anastasio Somoza and the beginning of both the Sandinista government and the US response to it. The next part will walk forward in time from there into the Iran Contra scandal of the 1980s.

The second thing I’d like to say is that this era is so important to remember. Nicaragua was pretty much ground zero for the US war on Central America in the 1980s. And yet, it is often obscured by discussions over what that country represents today. That’s unfortunate, and it only benefits those who would rather conceal the past — Namely, the US government, which was responsible for so much damage, destruction, and the loss of tens of thousands of lives in Nicaragua throughout the 1980s.

Finally, as you can imagine, many portions of today’s episode deal with harsh themes from the US war on Nicaragua in the 1980s including killings, torture, and terror attacks. If you are sensitive to these things or you’re in the room with small children, you might want to consider another time to listen.

OK. Here’s the show…

So in June 2023, my family and I visited the Nicaraguan town of Leon. It’s the second largest city in the country, after Managua. It was founded 500 years ago by the Spanish conquistador Francisco Hernández de Córdoba on land inhabited by the Chorotegas Indigenous people. Leon was the first capital of Nicaragua — And it was a former base for the Liberals, who often fought for power against the Conservatives in Granada.

Leon’s top attraction is its iconic cathedral. It’s the largest in Central America, and if you go up to the roof, the architecture of stark white domes and cupolas almost reminds you of something out of Greece. The smoking Momotombo volcano in the distance.

This day, we decided to go to a place called the Museum of Traditions and Legends. It’s a few blocks from the main square.

Just inside the main gate, there’s a little garden with a statue of a camouflaged Sandinista guerrilla fighter, and then you pass through this big, brick wall with turrets on the corners. Only then did I realize where I was. Before this was the Museum of Traditions and Legends, it was a prison — Carcel la 21. Prison 21.

This place is really crazy. So it’s a former prison that was liberated by the Sandinista army. There was torture. It’s just one big house with all these different cells that people were apparently taken to, with major repression and torture and killings throughout the 1970s.

That was the time of brutal US-backed dictator Anastasio Somoza. For decades, the National Guard would bring political prisoners and the disappeared here.

I’ll be honest, walking through the museum gives me chills. The bars are still on the windows. They have it set up so that each room you step into, there’s a new exhibition with large puppets or figurines showing different Nicaraguan traditions or legends, but the walls are all painted with black and white pictures of what used to be there: prisoners sitting on bunk beds playing cards. The National Guard lining people up, their hands and feet shackled. Images of people undergoing different forms of torture.

There’s these pages talking about exactly what type of torture happened in these buildings: injecting drugs, filing victims’ teeth, bathing their bodies in water and salt and then making them stand on electric wires. It’s just terrifying.

But also, at the same time, really beautiful that they can recuperate it, like we’ve seen in so many other places. Another reminder of the stories that remain. The history, terrifying history.

…The terrifying history of the violence of the past and the revolutionary struggle that would overthrow a dictator and usher in a wave of hope, not just for Nicaragua, but across the world.

That… in a minute.

[Under the Shadow theme music]

This is Under the Shadow — A new investigative narrative podcast series that walks back in time to tell the story of the past by visiting momentous places in the present.

This podcast is a co-production in partnership with The Real News and NACLA.

I’m your host, Michael Fox — Longtime radio reporter, editor, journalist. The producer and host of the podcast Brazil on Fire. I’ve spent the better part of the last twenty years in Latin America.

I’ve seen firsthand the role of the US government abroad. And most often, sadly, it is not for the better: invasions, coups, sanctions. Support for authoritarian regimes. Politically and economically, the United States has cast a long shadow over Latin America for the past 200 years.

In each episode in this series, I will take you to a location where something historic happened — A landmark of revolutionary struggle or foreign intervention. Today, it might look like a random street corner, a church, a mall, a monument, or a museum. But every place I’m going to bring you was once the site of history-making events that shook countries, impacted lives, and left deep marks on the world. I’ll try to discover what lingers of that history today.

Over the last two episodes, I’ve been walking you forward in time across the long history of US intervention, invasions, and occupations of Nicaragua. We left the last episode amid the brutal Somoza dictatorship, which would last for nearly five decades. Today, we dive from there into the 1980s — To revolution and the US war on Nicaragua.

This is Under the Shadow Season 1: Central America, Episode 10: “1980s Nicaragua Part 1: Revolution”.

[Music]

The year is 1978.

Dictator Anastasio Somoza, also known as Tacho, is in power. His family has ruled Nicaragua since 1937, since just a few years after Anastasio’s father, Anastasio Somoza García, ordered the killing of Augusto Sandino.

Somoza the father was the head of the National Guard, which the United States had trained and equipped. He took power after the departure of the US Marines marked the end of the United States’s longest military occupation in Latin American history — 21 years. We talked about that in depth in the last episode.

In 1939, US president Franklin Delano Roosevelt is alleged to have said of Somoza García, “He may be a son of a bitch, but he’s our son of a bitch.”

By the late 1970s, Anastasio Somoza the son has been in power for a decade. He took over in 1967 after his older brother — Dictator Luis Somoza Debayle — died of a heart attack.

Arizona State University History Professor Alex Aviña says Anastasio Somoza was a Cold War warrior.

Alex Aviña: He deployed that discourse to get help from the United States. He would position Nicaragua as on the front lines of Western civilization’s struggle against communism. He himself studied at military academies in the United States, so he’s very Americanized. He spoke perfect English. But he was a ruthless dictator.

Anastasio Somoza [recording]: I’m gaining support from the American people, which is what is important to me — Because I am a friend of the American people, and so are the Nicaraguans.

Michael Fox: That’s him speaking to press in Miami during a trip to the United States in 1979. He wears a suit, walks stiff and upright. He has a large mustache, big aviator glasses, a receding hairline, and a smug expression.

As unrest grew, Anastasio Somoza’s reign became increasingly brutal.

John Pilder: Anastasio Somoza founded a dynasty that ran Nicaragua like a family business for 44 years.

Michael Fox: In this documentary from the 1980s, Australian investigative journalist John Pilger stands on the edge of the Masaya volcano, just south of the Nicaraguan capital, Managua. White smoke pours out of the crater.

John Pilger: The Somozas were protected by a private army called the National Guard, which the United States created, paid, and armed. Somoza called them “his boys”, and they tortured almost as a sport. This is the Masaya Volcano, which, as you can see, is very much alive. One of the delights of Somoza’s “boys” was to drop his opponents from helicopters into the volcano.

Alex Aviña: The last decade of his rule, he really was forced to rely on brutal, overt political violence and terror against his political opponents, whether they were FSLN guerrilleros, who had regrouped after their military defeats in the late 1960s to become this really powerful force in the 1970s, but also more who scholars would refer to them as moderate elements of the political opposition.

Michael Fox: The FSLN. That’s the other name for the Sandinista National Liberation Front — An insurgency founded in 1961 to rid the country of the Somoza dynasty. It was named after Nicaraguan freedom fighter Augusto Sandino.

Somoza’s overt political violence and corruption turns the country against him and…

Alex Aviña: …In this situation, liberation theology plays a big role, as almost an ideological bridge between more radical revolutionary elements, like those that belong to the FSLN, with grassroots campesino workers, trade unionists in the countryside, and religious creyentes, religious folks throughout. It becomes an ideology that justifies self-defense and, eventually, revolution.

Michael Fox: By the late 1970s, the FSLN has gained tremendous strength and support. It launches a series of nation-wide insurrections.

Somoza responds by ratcheting up repression and violence.

Documentary: This is Nicaragua under martial law.

Michael Fox: The images of this documentary from the late 1970s show the rubble of buildings and twisted metal structures.

Documentary: The army stands guard over the ruins of a country. Ruins which bear witness to a national mutiny against a dictatorship so bereft of alternative solutions that it chose to bomb its own cities.

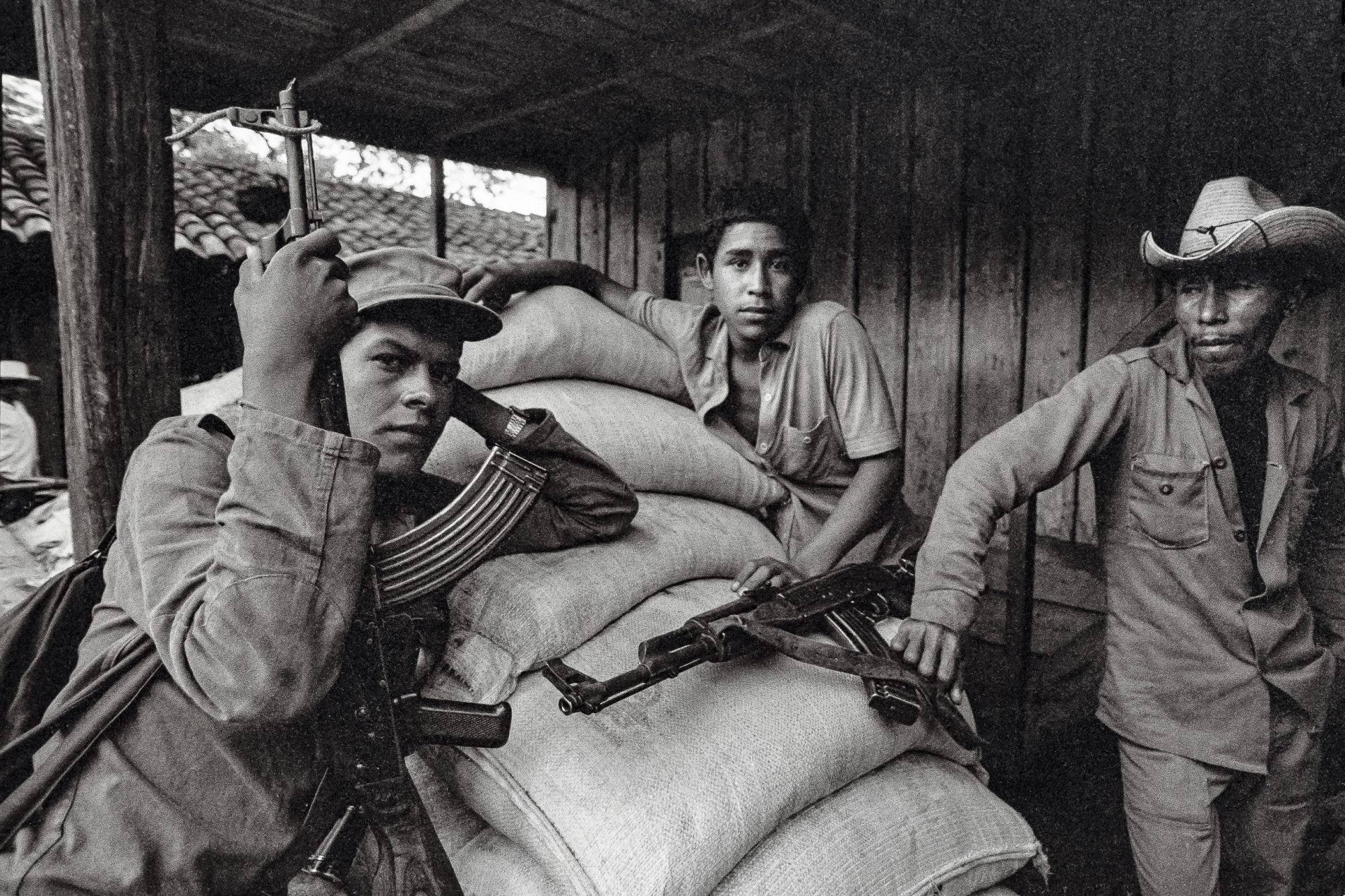

Sandinista: We have had to arm ourselves —

Michael Fox: — A member of the Sandinista insurrection tells a TV crew, tapping the automatic rifle in his lap.

Sandinista: This is the language that Somoza has used for the last 44 years, and this is the language that we are speaking. And he is understanding, because we are defeating him in the countryside and in the city.

Documentary: Meanwhile, the morale of the National Guard was slumping, and the rebellion was so widespread that Somoza’s forces were stretched to breaking point. By June, Somoza was ordering block-by-block street fighting from his fortified bunker in Managua.

By this time, the United States had lost all interest in propping up an unwanted regime.

Alex Aviña: So by the time the revolution breaks out in 1978, he faces an entire society with very few exceptions: the cliques around him, the National Guard that had been organized all the way back in the 1930s by the US, against a a broad, popular front of revolutionary resistance against his dictatorship that leads to his overthrow in 1979.

Michael Fox: Finally, July 17, 1979, Somoza resigns and flees the country. He goes into exile in Paraguay, then ruled by its own dictator, who would ultimately be in power for 35 years.

News Report 1: After 16 years of persistent fighting and seven weeks of outright civil war, Nicaragua’s Sandinista guerrillas today savored a total victory over Anastasio Somoza. By the thousands, the people of Nicaragua are pouring towards the capital of Managua to celebrate the revolution.

News Report 2: But for the Sandinistas, today was more than Independence Day. Today, Managua was theirs.

Marvin Ortega Rodriguez: The most important thing happened in the following days —

Michael Fox: — Says Marvin Ortega Rodriguez. He was a member of the Sandinistas, and he would go on to serve as Nicaraguan ambassador to Brazil and Panama.

Marvin Ortega Rodriguez: The entire society came out to support the FSLN. People who had never participated in any organization in their lives started getting involved and getting organized — Even some of Somoza’s former public officials.

Michael Fox: Marvin says he began in his community, coordinating the Sandinista Defense Committees. They were the local, community branch of the Sandinista movement after they overthrew Somoza.

Marvin Ortega Rodriguez: Every night, we were out in the streets doing community watch. But it wasn’t just a couple of people, it was the entire neighborhood. We had a tremendous sense of community.

William Robinson: In the early 1980s, the feeling is euphoric.

Michael Fox: That’s William Robinson. Today, he’s a professor of sociology and Latin American Studies at UC Santa Barbara. He arrived in Nicaragua in 1980 and lived there throughout the decade, first working with the Nicaraguan Committee in Solidarity with the Peoples, and then working at the state Nicaraguan News Agency.

William Robinson: You still get the sense of revolution in the air. There’s this incredible optimism. There’s this incredible outpouring of enthusiasm from poor people, from the barrios. There’s beehives of organization everywhere. Especially young people are so thrilled, and have endless, boundless energy. And I was young, I was the same age as all the young people, late teens, early 20s.

Eline Van Ommen: Obviously, the Sandinistas come into power with a radical program of social change.

Michael Fox: That is Eline Van Ommen, a historian of Latin America at the University of Leeds in the UK.

Eline Van Ommen: One of the major accomplishments when they come to power is this literacy campaign in which young Nicaraguans from the mostly urban areas, they become brigadistas. They go to the rural areas, the countryside, and they teach literacy skills to children, but also adults, because illiteracy rates were incredibly high.

Michael Fox: This tremendous black-and-white Nicaraguan documentary from 1980, produced by the newly formed Nicaraguan Film Institute, shows the rollout of the literacy campaign, or what the Sandinistas called La Cruzada Nacional, the National Crusade. They kicked it off in March, less than a year after the Sandinistas took power.

In the film, thousands of young Nicaraguans gather in Managua before heading off into the countryside to teach the people to read. The campaign was founded on similar literacy programs in Cuba and elsewhere. 100,000 young Nicaraguans participated in the program as teachers.

“I’m so proud that all of my children can participate in the literacy campaign,” says one mother, with her arms around her children. She says she has five kids — Another one died fighting Somoza.

It’s clearly a time of excitement and hope. The literacy campaign lasted five months and was a tremendous success. 400,000 Nicaraguans learned to read and write. Illiteracy dropped from just over half the population to under 13%.

“We are proud of what we’ve been taught,” says one campesino in the film, “because we’ll be able to bring this with us wherever we go. They didn’t teach this to us before because they didn’t want us to wake up. Today, we have awoken.”

But the literacy campaign did create tensions in Black and Indigenous communities on the Caribbean coast who didn’t speak Spanish as a first language. So, in late 1980, the new government launched a literacy campaign for communities there focused on English and Native languages.

And it didn’t stop there.

Eline Van Ommen: There’s healthcare programs, vaccination campaigns. So there is all this optimism about improving the standard of living and making this country more equal.

Michael Fox: The excitement spreads far beyond Nicaragua’s borders.

That is the British rock band The Clash. In late 1980, they released a triple album entitled Sandinista! — That’s Sandinista with an exclamation point at the end. It included this song, “Washington Bullets”, which looks at US intervention in Chile against Allende, the Bay of Pigs invasion in Cuba, and then celebrates the Nicaraguan revolution.

“Well the people fought the leader and up he flew”

sings lead vocalist Joe Strummer about the Sandinista revolution against Somoza.

“With no Washington bullets what else could he do?“

The Washington bullets would clearly come later, but hope is the feeling on the streets now.

Joan Krukewitt: Every day, there was news coming out of Nicaragua, frontpage headlines in the United States. There were news stories about Nicaragua. It was really exciting, especially for a journalist or a budding journalist.

Michael Fox: That’s reporter Joan Krukewitt in the 2007 documentary American Sandinista about US solidarity activists who came to support the revolution. Joan lived and worked in Nicaragua throughout the 1980s.

Joan Krukewitt: Nicaragua seemed to be like the center of the world.

Michael Fox: Alex Aviña.

Alex Aviña: This is the second successful revolution in Latin America in the Cold War era, so this is a political earthquake.

Michael Fox: The first, of course, was Cuba, 1959.

And the United States is concerned the dominos could fall across Central America.

President Jimmy Carter [recording]: As long as I am president, the government of the United States will continue, throughout the world, to enhance human rights.

Michael Fox: Even President Jimmy Carter. He’s remembered for his strong stance for human rights. He cut aid from Somoza during the last year of his rule. Carter re-upped it when the FSLN took power. But by early 1980, he’d also authorized the CIA to begin to support unarmed counter-revolutionary forces in Nicaragua.

Alex Aviña: Because they recognize that there are similar conditions throughout Central America: a small oligarchy, big landed elite, and a lot of disaffected civil societies. And you have the emergence of something like liberation theology that can serve as an organizing and ideological framework for disparate social elements.

Michael Fox: Remember, at this time, guerrillas are waging insurgencies against authoritarian US-backed governments in both Guatemala and El Salvador, as we’ve looked at extensively in this series.

Alex Aviña: And you start to see murmurings and movement to find ways to destabilize this fledgling new revolutionary government that, in its inception, was a multi-class, politically pluralist, social democratic movement.

Michael Fox: Alex explains that this is really important to keep in mind. The Sandinista movement that overthrew Somoza wasn’t some ruthless totalitarian regime that would impose their will on the masses; They were diverse, with strong support across the country. They wanted democracy. They wanted elections, and they would hold and win them.

This clip from a news report in the early 1980s shows the extent of the class diversity in the new Sandinista government.

News Report 3: Economists, lawyers, and even rich industrialists have taken positions in government. And United States and Western bankers, Nicaragua’s main hope for raising the massive cash loans it needs, are being assured that the new leadership is far from committed to a Cuban-style revolution. In fact, it’s claimed that 75% of the Nicaraguan economy is still in private hands, and will remain there.

Michael Fox: They did launch a land reform. At the time he fled the country, Somoza owned more than 20% of the country’s agricultural land. That was divided up to create state farms and cooperatives that could produce food for the country and drive exports. When campesinos demanded their own share, the Sandinistas listened, ordering that unproductive agricultural land also be expropriated and distributed.

But at the same time, William Robinson says, they tried to walk a tightrope so as not to alienate the traditional elites and powerful landowners.

William Robinson: Because of the urgency of the country defending itself from US aggression, the Sandinista policy was to hold back the class struggle, to support the so-called patriotic bourgeoisie, the land owners, big land owners that did not leave the country. The capitalists that didn’t leave the country and said OK, we will also not participate in the armed counter-revolution.

So, they got support in the form of the government saying to the peasants, don’t invade land. Saying to the workers, don’t strike for higher wages. Don’t confront the capitalists.

News Report 3: Sandinista spokesmen say they have been criticized on two sides: by some for being revolutionary Marxists, and by others for selling out the revolution to the capitalists. They insist neither is true. They want a pluralistic society and a mixed economy. The main goal is the reconstruction of Nicaragua.

Michael Fox: Alex Aviña.

Alex Aviña: What emerges from the 1979 Sandinista revolution is the type of revolution that Americans were saying in the ‘60s that they wanted for the region. But by the time we get to ‘79, ‘80, they’re like, no, actually we don’t want it.

It’s also a tiny… Like it’s what, 2.9 million people? It’s a tiny country with a tiny population, but it will assume this outsized presence in US foreign policy, especially after Jimmy Carter loses his reelection attempt to President Ronald Reagan. And that completely changes the dynamic of what’s really going to happen, which is essentially the US declaring war on Nicaragua for 10 years.

Michael Fox: That… in a minute.

[ADVERTISEMENT BEGINS]

Maximillian Alvarez: Hey, everyone, Maximillian Alvarez here, editor-in-chief of The Real News Network. We’re going to get you right back to the program in a sec, I promise, but really quick, I just wanted to remind y’all that The Real News is an independent, viewer- and listener-supported, grassroots media network. We don’t take corporate cash, we don’t have ads, and we never, ever put our reporting behind paywalls.

But we cannot continue to do this work without your support. It takes a lot of time, energy, and money to produce powerful, unique, and journalistically rigorous shows like Under the Shadow. So if you want more vital storytelling and reporting like this, we need you to become a supporter of The Real News now. Just head over to therealnews.com/donate and donate today. It really makes a difference.

Also, if you’re enjoying Under the Shadow, then you will definitely want to follow NACLA, the North American Congress on Latin America. NACLA’s reporting and analysis goes beyond the headlines to help you understand what’s happening in Latin America and the Caribbean from a progressive perspective. Visit nacla.org to learn more.

Alright, thanks for listening. Back to the show.

[ADVERTISEMENT ENDS]

President Ronald Reagan [recording]: It’s the fate of this region, Central America, that I want to talk to you about tonight. The issue is our effort to promote democracy and economic well-being in the face of Cuban and Nicaraguan aggression aided and abetted by the Soviet Union.

Michael Fox: William Robinson.

William Robinson: Of course, Reagan is elected in the end of 1980, and he makes it clear very soon that there’s going to be a major escalation of US hostility.

I think for me the key turning point is 1983, because up until 1983, there’s a lot of enthusiasm. Also the economy had not been shattered. People’s lives were improving. There were subsidies on basic consumption. There was health and education. The literacy campaign was ‘80 to ‘81.

So all of that starts to change, and 1983 is really the key year where it becomes clear that the United States is going to launch a war of hostility and escalation. A war to destroy the Nicaraguan revolution. And so the mood gets more somber, more concerning.

Michael Fox: Remember, this is thick in the Cold War.

Speaker 1: Members of the Congress, I have the high privilege and distinct honor of presenting to you the president of the United States.

Michael Fox: Alex Aviña.

Alex Aviña: He gives this famous address to Congress in 1983 where he gives us the domino theory, Central America version. That the Sandinista victory was going to unleash communist revolution throughout Central America, is going to lead to the downfall of Mexico, and eventually it was going to reach the United States. And then we get this movie, Red Dawn, which is precisely that.

Michael Fox: That’s a clip from the movie. If you don’t remember it, it’s pretty crazy. It’s been described as teen Rambo, where an adolescent Charlie Sheen, Patrick Swayze, and Jennifer Grey — You know, from Dirty Dancing — Well, they have to defend the US from an invasion of communist forces, including Nicaraguans.

Alex Aviña: Red Dawn is the fantasy, the fear that the US was going to be overtaken by the Nicaraguans, the Cubans, and the Russians.

Michael Fox: Like we have talked about often in this podcast series, US president Ronald Reagan saw Central America as ground zero for his proxy war against the so-called communist threat in the region. He backed bloody authoritarian regimes, waging war on their populations in Guatemala and El Salvador. He essentially turned Honduras into a US military base from which he would wage a decade-long invasion against the Sandinistas.

No country was more of a direct US battlefield than Nicaragua.

Alex Aviña: So the goal was to destabilize, to choke out this revolution. The goal of the Reagan administration was to declare war on this country. And that would, in a wartime footing, would force the Sandinista government to assume authoritarian measures, essentially, to survive.

And the way that the Reagan administration is able to do this, or one of the main ways, is to fund a bunch of ex-Somozista, ex-National Guard people, and create something that we now refer to as the Contras.

The other way was to essentially have an invisible economic blockade and to illegally mine the ports of Nicaragua, and to use what the CIA referred to as “unilaterally controlled Latino assets” to wage a CIA covert war against the Sandinistas to blow up oil depots.

Michael Fox: We dove into the training and funding of the Contras extensively in Episode 6 of this podcast about 1980s Honduras. If you haven’t heard that yet, I recommend you go back and listen now. As I mention, according to anthropologist David Vine, in the 1980s there were “at least 32 Contra bases alone in Honduras, Nicaragua, Costa Rica, and even Florida.”

And they were brutal.

Alex Aviña: The Contras start to take form in ‘81, ‘82, and right away they don’t really attack the Sandinista army. What they start doing, through incursions from Costa Rica and Honduras, was to wage war on Nicaraguan civil society. To attack “soft targets”, to attack and do horrific things to teachers, to civil workers, to doctors, to communities.

They were horrific rapists. They would kidnap young girls and essentially turn them into sexual slaves. They had hundreds of people that they kept in this way. The Contras were just monsters. And they were being financed and organized and trained by the United States led by Reagan.

Michael Fox: Miguel d’Escoto was a Catholic priest and the foreign minister of the Sandinista government throughout the 1980s. In this documentary from that period, he lays out what he says is the US responsibility for the Contra war on his country.

Miguel d’Escoto: They conceived it. They are directing it. They are financing it. And the United States is also arming it.

President Ronald Reagan [recording]: We have an obligation to be of help where we can to freedom fighters, lovers of freedom and democracy, from Afghanistan to Nicaragua.

Michael Fox: Peter Kornbluh is a senior analyst at the National Security Archive, which has worked to get documents declassified on US intervention and, in particular, South and Central America. And, of course, Nicaragua.

Peter Kornbluh: Ronald Reagan called the Contras freedom fighters, the George Washingtonians of modern Central America. But in fact they were vicious, repressive, brutal beyond description. And we were supporting them, if not leading them, if not doing some of our own operations and then letting them claim credit for them. So it was a bloody, overt covert operation.

The Contra War, I would say, became the most notorious and protracted CIA covert operation in modern history. And yet, all these years later, everybody’s forgotten about this. The Contras had no real backing, funding, training other than the United States after an initial few months of some Argentine agents, a small team of Argentine agents being in Honduras and Costa Rica.

Michael Fox: The Sandinistas armed and fought back. And they were more than clear about who was backing their adversaries.

“They are people from outside our country, people from outside our lives that are screwing us,” says one member of the Sandinista forces in a documentary produced in the ‘80s. He’s young, in a green camouflage uniform, leaning against a tree somewhere in the field. “Who’s financing the counterrevolution?,” he says. “It’s the gringos. Who’s sending the planes to do reconnaissance? It’s the gringos. So it’s the gringos that are waging war on us. If they weren’t financing the old National Guard, they wouldn’t exist. They would have been defeated 1,000 times over,” he says.

But news of the Contras’ brutality was getting out as international journalists began covering the abuses.

Jane Wallace: The Reagan administration has spent over $80 million funding the Contras guerrilla attacks inside Nicaragua. The questions center on who the Contras are targeting. It has become, some say, a dirty war.

Michael Fox: In this news story from the 1980s by the CBS television program West 57th, reporter Jane Wallace visits a village and speaks with an American nun about the Contra attacks.

Jane Wallace: The Contras, she says, are deliberately targeting civilians. Gregorio Devilo was orphaned by them.

Speaker 2: His family was murdered by the Contras in November when the baby was six days old.

Jane Wallace: The parents were murdered?

Speaker 2: Yes.

Jane Wallace: Other members of the family as well?

Speaker 2: A brother of the mother. His girlfriend. The 4-year-old brother of this baby. The Contras attacked about 20 of them one night.

Alex Aviña: As a result of some of this reporting that the US government could not ignore, we had a series of Boland amendments, named after the representative from Massachusetts, that forbid the US government from funding or giving any sort of support or financial aid to the Contras.

Michael Fox: So the Contras find their revenue streams dry up, And Reagan’s government decides to get both creative and illegal about how to finance its so-called freedom fighters in Nicaragua.

Peter Kornbluh.

Peter Kornbluh: The Reagan administration was so obsessed with overthrowing the Sandinistas and reasserting US domination control in the region that they violated the law of the land.

The American public and the US Congress said no, we’re not going to be supporting a counter-revolutionary effort to overthrow the Sandinista government. And the Reagan administration said, well, yes, we are. And if you don’t give us the money, we’re going to secretly get it.

Michael Fox: And that is where we will head next time, in Part 2 of this episode.

President Ronald Reagan [recording]: They are the moral equal of our founding fathers and the brave men and women fighting the French resistance.

Michael Fox: Even deeper into the CIA war on Nicaragua, but also to the solidarity movement that would respond, and the scandal that would rock the Reagan presidency,

President Ronald Reagan [recording]: A few months ago, I told the American people I did not trade arms for hostages. My heart and my best intentions still tell me that’s true. But the facts and the evidence tell me it is not.

Michael Fox: That is next time on Under the Shadow.

[Under the Shadow theme music]

As always, if you like what you hear, please check out my Patreon page: patreon.com/mfox. There you can also support my work, become a monthly sustainer, or sign up to stay abreast of the latest on this podcast and my other reporting across Latin America.

Under the Shadow is a co-production in partnership with The Real News and NACLA.

The theme music is by my band, Monte Perdido.

This is Michael Fox. Many thanks.

See you next time…