William Walker was a journalist, lawyer and physician from Nashville, Tennessee, who in 1855 invaded Nicaragua with a few dozen troops and conquered the country.

At the time, he was one of thousands of private US citizens who had their sights set on taking over foreign nations, all in the name of Manifest Destiny.

In this episode, host Michael Fox follows in the footsteps of William Walker as he recounts one of the most twisted stories of US imperialism in Central America—a story that still has lasting repercussions for Latin America, the United States and across the world.

Under the Shadow is an investigative narrative podcast series that walks back in time, telling the story of the past by visiting momentous places in the present.

In each episode, host Michael Fox takes us to a location where something historic happened—a landmark of revolutionary struggle or foreign intervention. Today, it might look like a random street corner, a church, a mall, a monument, or a museum. But every place he takes us was once the site of history-making events that shook countries, impacted lives, and left deep marks on the world.

Hosted by Latin America-based journalist Michael Fox.

This podcast is produced in partnership between The Real News Network and NACLA.

Guests:

Michel Gobat

David Díaz

Many thanks to Victor Acuña

Edited by Heather Gies.

Sound design by Gustavo Türck.

Theme music by Monte Perdido and Michael Fox. Other music from Blue Dot Sessions.

Follow and support journalist Michael Fox or Under the Shadow at https://www.patreon.com/mfox

You can also see pictures and listen to full clips of Michael Fox’s music for this episode.

For background, see Michel Gobat’s book Empire by Invitation:William Walker and Manifest Destiny in Central America (2018, Harvard University Press)

Transcript

Michael Fox: [Symphony tuning instruments] This episode is going to start a little bit different than what I had imagined because I just arrived to this farmhouse on the west end of Rivas, which is one of the main cities here in southern Nicaragua. Huge volcano overlooking… It’s on the edge of Lake Nicaragua, the southern side. The farmhouse itself, there’s this big, grassy knoll all around it, some old cannons sitting outside.

And this is one of the most historic places here. The farmhouse itself is made of adobe, wooden roofs with clay tiles that’s so traditional of this era.

What’s fascinating here is you have… I just arrived, and there’s the National Youth Symphony from Rivas is just setting up to practice this afternoon. They practice here every Tuesday and Thursday afternoons. We’re all sitting, and they’re just about to start playing.

There’s all these old wagon wheels, metal wagon wheels sitting on the side, and the grass stretches around, but the city of Rivas has really engulfed the farmhouse. This is the only thing left on this hill.

The reason why this is so important, this farmhouse itself, is because it was here that William Walker, the US filibuster, came in, invaded Nicaragua with a few dozen men, and this is one of the first places he came to when he first invaded Nicaragua on his plan to take over and control the country. There’s a whole library in the back here, which I didn’t even see before.

The year was 1855. William Walker, a physician and lawyer from Nashville, Tennessee, would not only invade Nicaragua with a small army of mercenaries, but he would take over and rule the country, not on behalf of the US military or even in the name of the United States, but in the spirit of Manifest Destiny.

It was only the first part in his plan to conquer all of Central America, and Walker was not the only random guy from the United States bent on invading and conquering other countries. There was a whole movement of them. But also a movement against them that would lead to the very concept of Latin America.

The Nicaraguan town of Rivas and this farmhouse on the Santa Ursula Plantation would be at the center of not one but numerous battles over two years that would be remembered as the struggles for the true liberation of Nicaragua, Costa Rica, and elsewhere. William Walker and his invasion of Nicaragua are virtually unknown in the United States today. His actions shaped history, but as we will see in this episode, not in the way that he hoped to. All of that in a minute.

[Under the Shadow theme music]

This is Under the Shadow, a new investigative, narrative podcast series that walks back in time to tell the story of the past by visiting momentous places in the present.

This podcast is a co-production in partnership with The Real News and NACLA. I’m your host, Michael Fox — Longtime radio reporter, editor, journalist, the producer and host of the podcast Brazil on Fire. I’ve spent the better part of the last 20 years in Latin America.

I’ve seen firsthand the role of the US government abroad and most often, sadly, it is not for the better. Invasions, coups, sanctions, support for authoritarian regimes. Politically and economically, the United States has cast a long shadow over Latin America for the past 200 years.

In each episode in this series, I will take you to a location where something historic happened, a landmark of revolutionary struggle or foreign intervention. Today, it might look like a random street corner, a church, a mall, a monument, or a museum, but every place I’m going to bring you was once the site of history-making events that shook countries, impacted lives, and left deep marks on the world. I’ll try to discover what lingers of that history today.

As you have probably noticed throughout the series, I have been traveling southward from Guatemala into El Salvador, Honduras, and now, today, into Nicaragua. Many of the episodes have focused on the 1980s, the role of the Reagan government in backing atrocious regimes.

President Ronald Reagan [recording]: If we provide too little help, our choice will be a communist Central America.

Michael Fox: But I’ve also gone further into the past to understand the Monroe Doctrine, United Fruit, and, for instance, the 1954 coup in Guatemala that would lead to the country’s genocide against Indigenous peoples.

Today, however, I’m walking even further back in time to understand a figure and an invasion that are nearly incomprehensible today but that left lasting repercussions, even though almost no one remembers or realizes it.

One thing I do want to point out before we continue, however, is that unlike most of this podcast series, which focuses on intervention by the United States’s government or military abroad, this episode looks at intervention by private US citizens acting on their own accord. Although the US government was not directly involved, as we will see, the United States was more than happy to recognize the actions of people like Walker abroad once they took power.

This is Under the Shadow Season 1: Central America. Episode 8: “Nicaragua, William Walker”.

To start this episode, we’re going to step back to a moment some of you have probably heard of. The year is 1848. Gold is discovered in the hills of California. It’s the start of the Gold Rush. By the next year, tens of thousands converge on the territory. It’s not a state yet, not until 1850, and that’s where the name the Forty-Niners comes from — You know, the football team. The Forty-Niners were the prospectors who flooded California. San Francisco becomes a booming port town overnight. 300,000 people would move to California in the coming years with the dream of making it rich.

Now, the image you probably have is of people making the trip west in covered wagons, but actually, half of those that arrived to California during those years did so over water. Steamships would transport gold seekers from New York or New Orleans to San Francisco via Panama or Nicaragua, the shortest land masses between the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. Remember, the Panama Canal wouldn’t be built for another 60 years, but overland transit routes in both countries would shuttle people from one coast to the other.

Nicaragua actually had the easiest go of it because of the huge Lake Nicaragua, the largest lake in Central America, second largest in all of Latin America — Just for comparison, Lake Nicaragua is almost 17 times the size of Lake Tahoe.

Business mogul Cornelius Vanderbilt set up the Accessory Transit Company in Nicaragua to do the job. Steamers would sail to San Juan del Norte on Nicaragua’s Caribbean coast. Passengers would then sail up the San Juan River into the lake, cross to the town of Rivas on the other side, where a stagecoach would be waiting to take them down to the Pacific Coast port town of San Juan Del Sur.

Costa Rican historian David Diaz says the world of the 19th century was way more globalized than we realize.

David Diaz: Sometimes we think that globalization started at the end of the 20th century with television and the Internet. But this world of the 19th century, it was globalized, largely with boats over the ocean. People came and went. There was the possibility of more transit because you didn’t have these harsh laws restricting the transit of people between countries. Travelers from that period spoke of a huge diversity of people making the journey West.

There was a huge number of different cultures and languages that they heard in the boats. It was a very rich world there because of this type of daily contact between cultures.

Michael Fox: Vanderbilt’s transit company was very soon shuttling roughly 2,000 people a day over the route, and it was not cheap. Among those who ventured West was a man named William Walker, a native of Nashville, Tennessee. He was a bit of a prodigy: a physician, a lawyer, journalist. He studied at several universities, not just in the United States, but also in Edinburgh and Heidelberg in Europe.

When the Gold Rush kicked off, he was co-owner and editor of the New Orleans Crescent newspaper. The next year, 1849, he caught a steamer from New Orleans and shipped off to San Francisco at the age of 25.

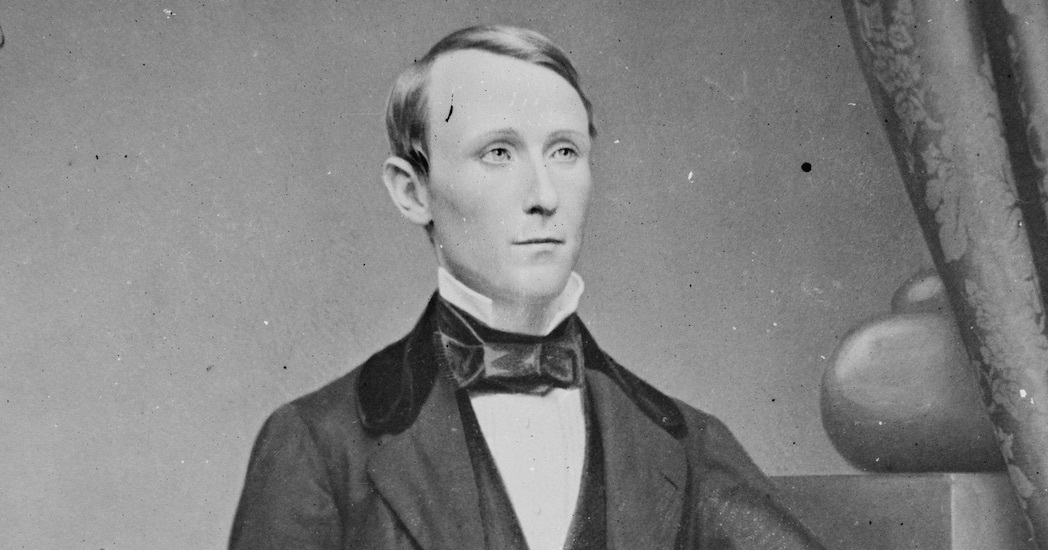

In probably the most infamous black and white picture of him from the 1850s, he stands in a tuxedo, his left arm resting on a pedestal, his short hair parted to one side, his eyes staring off into the distance. After reaching the West, he worked for a few years as an editor of The San Francisco Herald newspaper and unceremoniously fought three duels. But he had his sights set higher. William Walker would not only be caught up in the fever of the Gold Rush but of what would become known as filibustering.

Okay, so today, a filibuster is when a legislative representative talks for a long time in order to block progress in Congress.

Sen. Ted Cruz [recording]: I intend to speak in support of defunding Obamacare until I’m no longer able to stand.

Michael Fox: That was Republican Senator Ted Cruz back in 2013. He made it to 21 hours during which time he, among other things, read the Dr. Seuss classic Green Eggs and Ham.

Sen. Ted Cruz [recording]: That Sam I am. That Sam I am. I do not like that, Sam I am.

Michael Fox: Well, that is not the filibustering of old. Back in the mid-1800s, according to the Oxford Dictionary, a filibuster was “a person engaging in unauthorized warfare against a foreign country.”

And this was the thing. I want to bring in someone here who’s going to be with us for the rest of this episode and the next: Michel Gobat.

Michel Gobat: I’m a professor of history at the University of Pittsburgh, and my research has focused on US relations with Central America, mainly US intervention.

Michael Fox: Michel’s book, Empire by Invitation: William Walker and Manifest Destiny in Central America, was published in 2018. It’s an incredible resource for everything we’re discussing today.

Michel Gobat: The filibusters were… It’s an old term, but they became very prominent in the US after the US defeat of Mexico in the war of 1846 to 1848. This is the era of Manifest Destiny, so the US feels destined to expand its borders. Nowadays, Manifest Destiny is associated, I would say, in the US, nearly exclusively with expansion by land.

Few people remember that once the US actually hit the Pacific Coast, that is with the seizure of California, what you then have is efforts to expand by sea. Some of them went pretty far west, Hawaii and then eventually Japan with the Perry Expedition, but most of these expeditions went south to Latin America.

Michael Fox: And here’s the thing, most of the expansion at that time was not from the US government or even military, but from private citizens.

Michel Gobat: In doing so, they violated US law, particularly US neutrality law, and that’s why they were called filibusters. It’s from the Dutch and Spanish term for freebooters or pirates. Because they were violating US law, they were seen as pirates.

It also has a lot to do with the fact that many of these filibusters were young men who were living in port cities like New York, New Orleans, San Francisco. Those are the main hot spots for filibusters in this period. And the traditional view is that these were young men interested in violence, sex, and alcohol, and that’s what they did. They went and thought they would have a good time invading other countries.

So, thousands of filibusters invaded Latin American countries between 1848 and the outbreak of the US Civil War. Some went as far south as Peru, but most of these invasions targeted either Mexico or the Caribbean Basin, so we’re talking about countries like Cuba. I would say the three main targets are Nicaragua, Cuba, and Mexico. And they all failed except for the one by Walker.

Michael Fox: Two things that are really important to point out here. First, remember, this is just a decade before the start of the Civil War, and there is this long-standing internal conflict in the United States broiling over the practice of slavery. Many of the filibusters invading countries at the time are doing so with the hopes of bringing new slave states into the union. That was at least in part the situation in Texas.

Second, at this time, the mid-1800s, borders and territories are in flux as settler colonialism violently expands the United States.

Speaker: This is for Texas, Boys! This is for Texas and freedom!

Michael Fox: In his 2003 book, Manifest Destiny’s Underworld, historian Robert E. May writes that “The Texas Revolution of 1835 began as an uprising against Mexican rule by Anglos. However, so many private American military companies hastened to Texas once word of the uprising arrived in the United States that the Texas Revolution became transformed into the most successful filibuster in American history.”

He writes that more than three-quarters of all the soldiers in the Texan rebel armies at the time of the battle of the Alamo in early 1836 crossed the border into Texas less than six months before. In other words, they were the invading army, not the Mexicans.

Texas would become a state in 1845, California, 1850, only after Mexico handed it over to the United States along with most of the Southwest following the Mexican-American War, or what Mexicans call the War of Northern Aggression. But Utah, it’s not a state until 1896. Arizona and New Mexico, they don’t become states until 1912, another 60 years. In other words, the sky was the limit.

Walker first pointed his sights toward Mexico’s new northern border. The idea was like Texas 2.0. October 1853, Walker sets out with 45 men to conquer the Mexican territories of Baja California and the state of Sonora. It’s a sparsely populated region.

He captures the Baja capital, La Paz, and declares himself the president of the New Republic of Lower California. He puts the region under the laws of Louisiana, his home state, legalizing slavery.

He’s forced out within a few months by the Mexican government and a lack of supplies, and in California, he’s indicted by a grand jury for waging an illegal war in violation of the Neutrality Act, though a jury acquits him in only eight minutes.

It’s shortly thereafter that Walker gets an enticing proposition. A civil war is raging in Nicaragua. It’s the Liberals versus the Conservatives, and Walker gets an invitation from the Liberal Democratic Party. They’ve heard of Walker’s escapades in Mexico, and they’d like him to help them defeat their adversaries. For Walker, Nicaragua is particularly interesting. Remember, it’s a major transit hub for east-west travel. It’s also the top competing location alongside Panama for the construction of a canal that could unite the Pacific and Atlantic oceans, so Nicaragua…

Michel Gobat: …Was strategically and economically important at that moment because of its geographic position. So Walker, like other US expansionists, thought that whoever controls Nicaragua would control a very important piece of land.

Michael Fox: Walker set sail from San Francisco May 3, 1855.

Michel Gobat: He first lands in northwestern Nicaragua, close to basically the bastion of the Liberal Party that invited him. And so he gets there with 59 men. He’s there to help the Liberals win the civil war against the ruling Conservatives. Their headquarters are in the second largest city of Nicaragua called Granada, which is further south.

What he does is he thinks he can do it all on his own. He sails from this northwestern corner of Nicaragua to the southwestern corner, basically where Vanderbilt has his Pacific port, and from there he wants to then just march from there northwards to Granada. That’s a miserable failure, in large part because he doesn’t trust the Nicaraguan troops that join him.

Michael Fox: This is the First Battle of Rivas, when they occupy the farmhouse where I started this episode. They’re able to escape, and Walker sails back to León, but he realizes he needs help. So, this time, he gets reinforcements from one of his top Liberal supporters, José María Valle. Valle was a leader of a powerful peasant movement years before. Some Conservatives in the country even call him a communist. He hopes Walker will bring radical transformations to Nicaragua.

Michel Gobat: Valle provides him with most of his troops. So, Walker does the same thing again. He sails south to the port called San Juan del Sur and replicates the whole thing, with the difference that he then commandeers some lake steamers that Vanderbilt uses to transport the gold rushes across the lake and uses that to attack Granada, and seizes Granada, and basically becomes the strongman of Nicaragua. But the only reason he’s able to do that is because he relies heavily on the troops provided by Valle.

Michael Fox: I am riding in the back of a carriage. It’s white, bows tied to the sides, horse-drawn, two horses leading the way. Their names are Mercedes and Benz, and it feels like something out of Cinderella. You’ve got these big long metal wheels.

And we’re riding through Old Town Granada. The houses are all painted these pastel colors. It’s really, really quaint, the old tiled roofs and cobblestone streets. It feels like you’re stepping out of time in a lot of ways. But this was the town where William Walker ran the country. This was his capital.

Michel Gobat: What’s interesting is that Walker, initially, he’s offered the presidency by both the Liberal leaders and the Conservative leaders who are defeated. What is now largely forgotten, especially in Latin America, is that at that time, a lot of Latin Americans admired the US as their political and economic model, and so there was strong support for US annexation in places like Nicaragua at that time, particularly among the elite sectors.

So, both Liberal leaders and Conservative leaders offer Walker the presidency, but he refuses. Instead, he installs a puppet president, a Conservative. And initially, his rule is pretty moderate.

Michael Fox: Walker’s main goal at this point: consolidate power, win diplomatic recognition from the US government, recruit followers from the United States — Not just for his army, but whole families to come settle in Nicaragua.

Roughly 12,000 families arrive over the next two years. Walker launches a bilingual weekly newspaper, El Nicaragüense, which makes the rounds in Nicaragua but is really for distribution on the East Coast of the United States. He makes English an official language, and he legalizes slavery, a practice abolished across Central America in the 1820s.

Remember, Walker is from Tennessee, a state in the South where slavery is legal at the time, and that is how Walker is often portrayed today, in the rare cases that he is portrayed in the United States: as a Southerner who wanted to create a slave-holding society in Nicaragua. But Michel Gobat says, according to his research, that’s not really accurate, and mostly based on a book Walker would later write in order to drum up support in the South for future expeditions in the region.

Michel Gobat: It’s true that a number of pro-slavery Southerners hooked up with Walker in Nicaragua, but the majority of the supporters came from the North, and they included families who just deemed Nicaragua the new California. They were essentially what we would now call settler-colonists. They thought that they would have a better life by settling in Nicaragua.

It was easy to get to Nicaragua because of the Gold Rush, and Walker, once he comes to power, makes a deal with these shipping companies that allows him to transport all his would-be followers from the US to Nicaragua for free.

Michael Fox: In his research, Michel found that others who arrived were actually political radicals from both the United States and Europe who believed Walker would push to transform the state for the better.

Michel Gobat: This is a moment in US history where you have a lot of moral reform movements, often associated with abolitionism, temperance activities, suffrage movements, and members of these movements all hook up with Walker.

Michael Fox: At this moment, Walker actually has a good deal of support from Nicaraguans on the ground as well. Liberals from the popular sectors, campesinos, artisans, people who hoped US democratic traditions and culture would rub off.

Meanwhile, for US government officials, they didn’t like Walker breaking neutrality laws as a filibuster, but they are more than happy to embrace him once he has taken power. The United States recognizes his government, allowing Walker to receive weapons and recruits legally from the United States.

Michel Gobat: Once he feels secure in power, that’s when Walker decides, it’s my time. I’m going to now seize complete power. And that’s when he promotes all these political reforms that, on the one hand, open up the political system to the poor — So just like what people like Valle wanted. Makes it easier for them to vote, people are now elected directly. But he then abuses these democratic reforms to stage a rigged presidential election that he wins.

He still maintains the support of radicals like Valle because, at the same time, he’s carrying out what his regime calls a revolution. So, this revolution has a political component, as I just mentioned, is opening up the political system to the poor, but it also goes after the economic power of local elite.

Ed Harris: It is I who shall save the life of this country!

Michael Fox: That’s the voice of Ed Harris playing Walker in the 1987 acid trip of a movie by the same name about the filibuster’s escapades in Nicaragua. In the movie, Walker is always clean-shaven and immaculately dressed in a slick black suit and Western hat. He’s portrayed somewhere between a mystic who strides into battle without fear of being shot or wounded, a political strongman, and a megalomaniac who believes he is bringing liberty and redemption to Nicaragua.

That’s probably not far off, but William Walker is complicated. It seems he really is trying to do good. He’s rebuilding cities — Remember, the country is coming out of years of civil war.

Michel Gobat: He also promotes public education. He promotes women’s suffrage, which is, back in the 1850s, a pretty radical thing. I have this playbill of a musical that was very popular in the US. I think the playbill is from when it was on Broadway, and there you can see Walker is seen as the hope of freedom. You can see the strong, Liberal bent.

Michael Fox: Walker also goes after the economic power of local elites. His regime starts confiscating landed estates, the basis of elite power, plantations of sugar, cacao, indigo, key sources of revenue. The problem is, he alienates his Nicaraguan supporters by giving this land over to US settlers.

Michel Gobat: That starts creating tensions between Walker’s US followers and his Nicaraguan followers, and that’s the beginning of the end of Walker.

Michael Fox: But for Walker, Nicaragua is only just the beginning. That in a minute.

[ADVERTISEMENT BEGINS]

Maximilian Alvarez: Hey, everyone, Maximilian Alvarez here, editor-in-chief of The Real News Network. We’re going to get you right back to the program in a sec, I promise. But really quick, I just wanted to remind y’all that The Real News is an independent, viewer and listener-supported, grassroots media network. We don’t take corporate cash, we don’t have ads, and we never, ever put our reporting behind paywalls.

But we cannot continue to do this work without your support. It takes a lot of time, energy, and money to produce powerful, unique, and journalistically rigorous shows like Under the Shadow.

So, if you want more vital storytelling and reporting like this, we need you to become a supporter of The Real News now. Just head over to therealnews.com/donate and donate today. It really makes a difference.

Also, if you’re enjoying Under the Shadow, then you will definitely want to follow NACLA, the North American Congress on Latin America. NACLA’s reporting and analysis goes beyond the headlines to help you understand what’s happening in Latin America and the Caribbean from a progressive perspective. Visit nacla.org to learn more. That’s N-A-C-L-A.org.

All right, thanks for listening. Back to the show.

[ADVERTISEMENT ENDS]

Michel Gobat: He’s trying to create an empire that would be independent of the US, so an empire that would consist of all the five Central American states of that era. So Nicaragua, Costa Rica, El Salvador, Honduras, and Guatemala, and that empire would be allied with the US, but independent of the US.

People don’t remember this anymore, but this is the Thomas Jefferson path of US expansion. Jefferson was an expansionist, but he did not primarily believe that it was the role of the US state to expand at borders. Rather, he thought it was the role of US farmers, the Yeoman Farmers, these US settlers, that they would go out and conquer new territory, establish their own independent policy that would be allied with the US.

So, this is the path, for example, that you see happening in Texas with the rise of the Republic of Texas. Another key example is the efforts of Mormons in present-day Utah to create their own state called Deseret, and one could even argue that the Bear Republic of California also follows this path. So, Walker’s not an outlier. He’s trying to create this empire.

Once he’s in power, early on in 1856 he decides to invade Costa Rica as the first way to expand his power beyond Nicaragua.

That fails miserably. It triggers a counter-invasion of Costa Rica that nearly succeeds in kicking out Walker. It fails because, contrary to Costa Rican’s hope, Nicaraguans didn’t rally to the Costa Rican cause. Instead, Walker survives because radical Liberals led by Valle help him withstand the Costa Rican offensive. But that’s the last time Walker actually tries to invade another Central American nation. From then on, he’s always on the defensive.

Michael Fox: Walker’s army faces the invading Costa Rican forces in southern Nicaragua, where they fight the second battle of Rivas, but the Costa Ricans retreat due to a nasty bout of cholera.

Michel Gobat: The summer of 1856 is the high point of Walker’s rule, and that’s when he launches this revolution. That revolution, I would argue, that’s the beginning of the unraveling of Walker because it creates all these tensions in the Nicaraguan countryside, a lot of violence, and, like many revolutionary regimes, Walker responds to this violence with more violence. That’s also the beginning of the Central American offensive.

Michael Fox: Remember, the Costa Ricans had retreated, but now they regroup and rally troops from the other Central American countries, who all provide battalions to fight Walker and his threat to the region.

Michel Gobat: Still, the rainy season in Central America, as you know, can make travel very difficult, particularly when there are no roads, when these dirt roads turn into mud banks. But then September, October, the rainy season starts to end, and then they start advancing into Nicaragua. And because of all the violence associated with Walker’s revolution, Nicaraguans are now less supportive of Walker. Some of them join the Central American offensive.

Walker makes a lot of military blunders. By November, his control is basically reduced to the city of Granada. And then he decides that he should abandon Granada and moves further south to Rivas, which is on the Transit Road. The Transit Road is, essentially, the road that Cornelius Vanderbilt constructed to transport the gold rushers across the isthmus.

Michael Fox: The Transit Road is essentially Walker’s lifeline to the United States. He’s still getting weapons and recruits, which is why he thinks it’s a good idea to relocate his capital there. On his way out of Granada, he orders a battalion to torch the city. They leave a sign at the dock. It reads, “Here was Granada.”

Michel Gobat: His torching of his former capital is so horrific, and also had a lot to do with the violence that accompanied the torching of his capital. It was supposed to just be carried out in a day or two, but because of heavy rains, it was delayed. And so Walker and most of his men had already left Granada for Rivas. There were just a couple hundred left behind.

They got drunk, and they committed a lot of violence. They did a lot of rapes, and it’s that horror that accompanied the burning of Granada that turned a lot of Liberals and that ensured that Liberals who had formerly supported Walker would not go back to him.

Michael Fox: Back in Rivas, Walker thinks he can still survive because he controls the transit route, but not for long. See, while he was in power, Walker had seized Vanderbilt’s transit company and handed it over to a pair of his US subordinates in exchange for financial and logistical support. Now, however, Vanderbilt responds by backing the Costa Ricans with the hopes of regaining control of his ships.

It pays off. The Central American Allied Army gets control of the transit route and essentially lays siege to Walker. The year is 1857. Less than two years have passed since the filibuster arrived.

Michel Gobat: On May 1, he’s forced to surrender. And the only reason he’s not lynched by the Central American Army — Because they really want to execute him — Is because there’s a US Navy ship anchored very close to Rivas in San Juan del Sur, which is the Pacific terminal that I mentioned before, constructed by Vanderbilt.

That warship had been there for various months, and the commander goes to Rivas, to Walker’s headquarters in Rivas, and arranges the terms of surrender. And Walker’s then able to leave with the help of this US Navy captain, unscathed. He survives, and he goes back to the US.

Michael Fox: When he was received after leaving Nicaragua, he was received back to the United States, and they received them with a hero’s welcome. Of course, the US recognized his regime or his government, and people were really excited about the idea that gringos could go to other countries, invade them, take them over, and proclaim themselves president. They saw it as a way of expanding Manifest Destiny.

And it did not end well. Walker would try to return to Central America three times. He’s delusional. I see him as a cross between Don Quixote and Lawrence of Arabia, but with a Southern accent. He believed he still had widespread popular support.

But then Trujillo, Honduras.

There’s a tombstone in the old cemetery in Trujillo on the Caribbean coast. The tombstone is a big, rectangular, concrete slab that’s risen off the ground on one end. There’s a little, waist-high, rusted, white, metal fence surrounding it. Flowering plants grow just inside. On the tombstone read the words, “William Walker, Fusilado, shot by firing squad. Sept. 12, 1860.”

Today, Concepcion Alvarenga cares for the cemetery. He’s up in age with a thin, gray mustache and a plaid shirt. He’s been at it for more than a decade.

Concepcion Alvarenga: William Walker’s tomb is visited by a lot of people. They take a lot of pictures, some even lie down on the ground to take pictures with him.

Michael Fox: Back in 1860, Walker was on his third attempt to regain control of part of the region. He landed on the Caribbean coast of Honduras. There he was captured by a British warship, which handed him over to Honduran authorities, and so went the life of America’s most illustrious filibuster.

Though he is all but forgotten in the United States, he’s more than remembered in Nicaragua and throughout the region. But not for his accomplishments. Riding around Granada, Walker’s name comes up constantly.

It’s funny. Granada is really funny. It’s like William Walker has this subtle, oversized presence throughout the cities in plaques all over the place. William Walker, this person opposed William Walker. William Walker was here. William Walker stayed here. This was William Walker’s house.

And it’s really interesting because he was only president for two years, but it overshadows and has overshadowed everything. But he was such an unbelievable moment in Nicaraguan history that this guy from the US with 50 soldiers would try to invade another country and proclaim himself president. It’s just mind-boggling. It’s mind-boggling.

“They teach the kids,” says Alfredo César Dávila, who’s been giving horse tours in Granada for nearly a half-century. “They tell them he came here. And I have grandchildren who ask me about William Walker, and I have to explain things to my grandkids because there is a lot of history,” he says.

And not just in Granada. Nicaragua’s most important Independence Day celebrations aren’t held on Sept. 15, the day of the country’s independence from Spain. They happen on the day before, to commemorate the 1856 Battle of San Jacinto, when Nicaraguan troops defeated a group of 300 filibusters under the command of the former newspaper owner and Boston native Byron Cole.

Among Nicaragua’s most beloved heroes is Emmanuel Mongalo y Rubio. That’s the marching band from a high school named after him. He was a teacher who fought against Walker and the filibusters in the First Battle of Rivas, setting fire to the farmhouse they were in and forcing them to flee. The date was June 29, [1856]. Today, June 29 is the Day of the Nicaraguan Teacher in honor of Mongalo y Rubio.

And not just in Nicaragua. In downtown San Jose, Costa Rica, about a block from the Supreme Court and the Legislative Assembly, is a huge statue in the middle of a park. It’s called the National Monument, and it honors the United Central American Army’s fight against Walker and the filibusters. The statue depicts five women fighting a man, William Walker. Each of the women represent a different Central American country that fought in the war against the filibusters.

Costa Rican historian, David Diaz.

David Diaz: A woman is trying to hit him with a sword, that’s Costa Rica. There’s another woman lying on the ground humiliated by the filibuster, that’s Nicaragua. And then there are three other women representing Honduras, El Salvador, and Guatemala that are supporting Costa Rica.

Michael Fox: David explains that this is the country’s most important monument. Back in the day when it was erected at the end of the 19th century, it was even more imposing.

David Diaz: At that time, it was in Costa Rica’s most important location, right in front of the last train station on the way up from the Atlantic Coast. So, this was one of the first things you would see as you arrived in San Jose. At the time, there were no big buildings in the city, and when you got off the train, you were on this hill, and you could see the rest of San Jose, and this monument was right in front of you, teaching you an official history lesson of Costa Rica.

When Costa Rican historians in the late 19th century were looking for important events to honor in their young nation, they didn’t find an independence struggle as had been fought in Mexico or South America. So, they picked up the war against Walker and called it the real independence of Costa Rica.

Michael Fox: And it’s still celebrated today on Sept. 15, Independence Day. Independence from Spain and from the filibusters who tried to invade their country. The National Monument was erected on Sept. 15, 1895. Another statue was erected on Independence Day around that same time for the country’s most epic hero, Juan Santamaría.

He was a drummer during the Second Battle of Rivas in 1856, and like Nicaragua’s Mongalo, y Rubio, he too is remembered for burning the filibusters out of a farmhouse, though in a different battle.

As the story goes, Santamaría was shot and killed. His figure today, though, is larger than life. There’s the monument, a museum that’s named after him, and even the country’s main airport.

Flight Attendant: Ladies and gentlemen, Spirit Airlines would like to be the first to welcome you to San Jose.

Michael Fox: If you’ve ever flown in or out of Costa Rica, you’ve probably done so at the Juan Santamaría International Airport. Costa Ricans also hold national celebrations for two battles against the filibusters each year: March 20, the Battle of Santa Rosa, and April 11, which remembers Santamaría’s heroism.

“For me, this is really important,” said one woman interviewed during April 11 commemorations, “because we’re celebrating something that happened a long time ago, but we still remember it.” David says he remembers when he was a child at school. Each year, they would do a performance of Santamaría burning out the filibusters.

David Diaz: We would make a house with bamboo and dry leaves and branches. The boys who were blonder and whiter, they played filibusters inside the house, and the boys with darker skin were the Central Americans. One of them was Juan Santamaría.

And it was crazy because we used real fire. The boys would go and set fire to the house with the other children inside, and they’d have to run away. I don’t know how nobody died in that performance, but we did it every April 11 even though, in reality, it wasn’t really such an important event in the war.

Michael Fox: Memory, how the past is remembered, how it’s forgotten, how it’s memorialized. This really hits home for me again and again walking the streets of Nicaragua, San Juan del Sur, Rivas, Granada.

But it’s really fascinating to be in this place with so much history tied to the United States, and yet, so much history that we in the US don’t know at all. Yet, it’s so important to remember just how much gall, just how terrifying people were at that time, supporting the ideas of Manifest Destiny and the idea that the US would expand its span forever.

Historian Michel Gobat says this concept is tremendously pervasive. It runs deeper than you can possibly imagine, and it has influenced US policies until today.

Michel Gobat: If you see Walker simply as a pro-slavery expansionist, well, his story becomes irrelevant with the defeat of the South and the US Civil War because slavery is abolished. But I realized that Walker was actually not the end of something, but the beginning of something new. That is, US efforts to spread democracy abroad.

What’s interesting about Walker is that this is clearly part of Manifest Destiny. If you look at the definition of Manifest Destiny, it’s not just that the US is destined to conquer other countries, but it is to spread the US way of life that is associated, scholars would argue, with capitalism, but especially with democracy.

So, yes, the US proponents of Manifest Destiny really felt that the US had this role, this universal role of promoting democracy. The US was seen at that time as the redeemer nation of the world.

President George W. Bush [recording]: Today, the people of Iraq have spoken to the world, and the world is hearing the voice of freedom from the center of the Middle East.

Michael Fox: Michel says he was developing the idea for his book on Walker in the early 2000s as George W. Bush was spreading a narrative of democracy promotion as justification for his invasion of Iraq.

Michel Gobat: They don’t use the term Manifest Destiny, but a lot of scholars would argue that the terms they use, in many ways, reflect Manifest Destiny, so that’s why I think the Walker episode is so interesting. Because many people believe that this US effort to promote democracy via military intervention is a more recent phenomenon, or one that goes back to Woodrow Wilson in the early 20th century. But they see it, essentially, as something coming from above, from the state.

But if you see it in terms of Manifest Destiny, you’ll see that it’s much more deeply rooted in US political culture or even in popular culture. Manifest Destiny is not a government proclamation. It’s a popular spirit, a popular feeling, a popular ideology. And so that complicates the role US interventionism abroad plays in US history. It’s not necessarily just simply a Washington thing. It’s much more part of the US DNA than commonly thought.

Michael Fox: The 1987 movie Walker hits the nail right on the head.

Speaker 2: Walker.

Ed Harris: It is the God-given right of the American people to dominate the Western Hemisphere. It is the fate of America to go ahead.

Speaker 3: Do you prize democracy, Walker?

Ed Harris: More than my own life.

Michael Fox: But Walker’s movement and victory in Nicaragua also creates a counter-movement, not just in Nicaragua, Costa Rica, or Central America, but across the region. Scholars say Walker was the impetus for the very idea of Latin America.

Michel Gobat: What scared the hell out of a lot of Spanish-American governments, as well as the Brazilian government, was that now filibusterism was no longer seen as a piratical enterprise, as an illegal enterprise, but one that now had the official support, the official sanction of the US government. And that led many Spanish-Americans and Brazilians to fear that now they’re going to be the next target.

Because what’s interesting is that the Walker episode created a lot more anxieties in present-day Latin America than the US victory over Mexico in the war of 1846-48, even though that victory led to the US conquest of the largest Latin American territory ever, and Walker disappeared after two years.

The reason why Walker was much more of a threat to South Americans was the fact that this was expansion by sea and not by land. With the case of Mexico, by the time US troops, if they’re going by land to reach Patagonia, that would take a while. But sea is a whole different story.

So, that led a lot of these South American countries, including Brazil, to forge a military alliance against US expansion, and it’s in that context that you get the rise of the idea of Latin America.

Michael Fox: In other words, the concept of Latin America arises in response to the threat from Walker, as does a renewed sense of Central American identity.

Historian David Diaz.

David Diaz: When the events occur with Walker and the filibusters, there are newspapers in El Salvador, Guatemala, and Costa Rica that begin to use the concept of a Central American identity. Not only Latin, but specifically identifying those who live in the region between Guatemala and Panama. They have a particularity that they share history, they share culture, they share many things, and that makes them a group called Central Americans.

In 1856, a newspaper in El Salvador even uses the term “Raza Centroamericano”, or Central American race, in opposition to the Anglo-Saxon race represented by Walker and the filibusters.

So, together with the concept of Latin America, the war against the filibusters reaffirms the idea that there is a Central America. That might seem obvious now, but it was not back in the day.

The legacy of Walker’s impact is impressive, for Costa Rica’s nationalism, the historic significance, from language, to the definition of the geographic region, and the very concept of a “Central American” race.

Michael Fox: Juan Santamaría’s drums were silenced outside the farmhouse in Rivas more than a century and a half ago, but the music plays on. The musicians in the youth orchestra say they learn about Walker in school. It’s a cautionary tale of ideas, culture, and institutions invited in and then imposed on them from abroad.

“We have to preserve our traditions,” says Isaac Javier Lopez Duarte. He’s a young trumpet player. He stands out behind the farmhouse on a stretch of grass that was occupied by Walker and his men almost 170 years ago. “If you lose your traditions, you lose your country, because that’s what it means to be Nicaragüense. The music, the dance, the culture, the events,” he says. “So many things.”

So many things.

That is all for Episode 8. Next time, I bring you back to Nicaragua to another occupation, but this time at the hands of US Marines in what would become the longest US occupation in the history of Latin America, and set the scene for the brutal Somoza Dictatorship and the Sandinista Revolution. That’s up next on Under The Shadow.

For this episode, I’d like to particularly thank Michel Gobat, David Diaz, and Victor Acuña for their guidance and interviews about Walker and this crazy period in US and Latin American history.

As always, if you like what you hear, please check out my Patreon page, patreon.com/mfox. There you can also support my work, become a monthly sustainer, or sign up to stay abreast of all the latest on this podcast and my other reporting across Latin America.

Under the Shadow is a co-production in partnership with The Real News and NACLA. The theme music is by my band, Monte Perdido.

This is Michael Fox. Many thanks. See you next time.