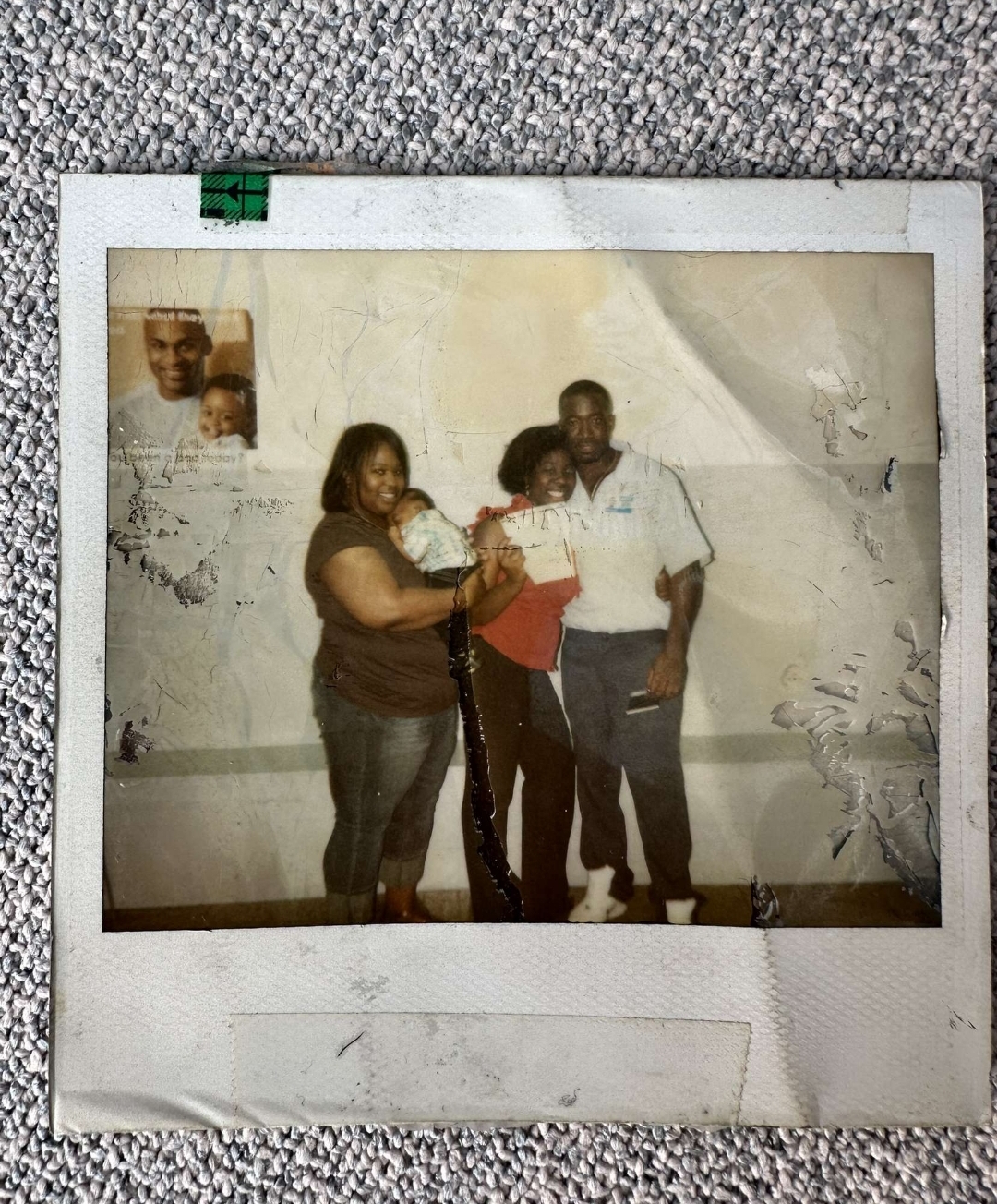

The prison system keeps millions of families from celebrating Father’s Day together. For Alexia Pitter of Families Against Mandatory Minimums, separation from her father, Gasi Pitter, has been a lifelong reality. Kept from even embracing her father during prison visits as a child, Alexia’s struggle to build and maintain a relationship with Gasi has required taking on the entire prison system. After believing for many years her father would never be released, Alexia is now fighting for her father’s release. Rattling the Bars explores this story of a brave daughter’s love, and one family’s determination to resist.

Additional links/info:

Studio Production: David Hebden, Cameron Granadino

Post-Production: Cameron Granadino, Alina Nehlich

Transcript

Mansa Musa:

Welcome to this edition of Rattling the Bars. I’m your host, Mansa Musa.

Joining me today is Alexia Pinter, the daughter of an incarcerated, imprisoned, enslaved Black man. More importantly, he’s her father, and we’re doing a series on Father’s Day.

But more importantly, we are trying to highlight the impact that the prison industrial complex, the new form of plantation, has on families: and why this system that’s supposed to be designed around humanity ceased to apply humanity, or humane behavior, towards families. Welcome to Rattling the Bars, Alexia.

Alexia Pitter:

Thank you. Thank you for having me.

Mansa Musa:

All right, tell our audience a little bit about yourself.

Alexia Pitter:

Absolutely.

Mansa Musa:

Yes.

Alexia Pitter:

So as you said, my name is Alexia Pitter. I work for an organization called FAMM, which is Family Against Mandatory Minimums.

I’m a senior associate there of Family Outreach and Storytelling. I tell a lot of stories from the formerly incarcerated perspective, but then also people who are still incarcerated. So I’m able to have that dialogue.

My loved one, my best friend in the world, is my father. He’s been incarcerated since I was three years old. I’m now 27, so I really grew up seeing my father in prison. I don’t really know him outside of being behind bars, and that was very hard for me.

I remember when I was around three, four years old, and I went to visit my dad for the first time. I wanted to just give him a hug. Like any child does, I’m just rushing and I’m like, “Daddy!”

The guards came over, the correctional officer, and said, “No, you’re not allowed to hug him. You’re not allowed to touch him. You need to sit right there.” They were just watching us the whole time in the visiting room.

I remember trying to understand why I was here with my dad.

Mansa Musa:

Right, right.

Alexia Pitter:

I’m three, four years old and I can’t hug him and I can’t touch him. And that’s what I need so much in that moment; I need that love.

After a while I was numb to it. If I was seeing my dad, the way I was able to process it was, “Well, this is just his home. This is where I see my dad. I’m not able to touch him. I’m not able to hug him. But this is his home, and this is just our new norm.”

Then when I was about 15, 16, I went to see my dad. And I looked through the window as he’s getting ready to go in the visiting room. He has handcuffs and foot cuffs on, and his head is down. And that truly changed my life and my perspective, because to me, my dad was my hero.

He’s the one who taught me how to heal. He’s the one who taught me about Marcus Garvey and Malcolm X and all the amazing work of the Civil Rights Movement and the Black Panther Movement. Everything that I really knew about my identity, where I came from, healing, mental health and things like that, came from him.

But in this moment he just seemed so small, and I just couldn’t understand why he was in chains. And to process that was so hard for me.

I remember asking my mom, “Why is Daddy in chains? He would never do anything wrong. Why do they have him confined in this way?”

And she was just, “This is the way it is, and this is just his lifestyle. And unfortunately, this is where we are.”

So that was the first time that I really acknowledged that this wasn’t just a separate home for my dad.

Mansa Musa:

Right.

Alexia Pitter:

This was prison, and he couldn’t leave when he wanted to. I couldn’t see him when I wanted to. And that just opened more of a dialogue with us. Because for a long time, I didn’t ask my dad why he was in prison.

Mansa Musa:

That’s right.

Alexia Pitter:

And I really believe that my fear was if I knew, it would be too scary that we just couldn’t continue to have our relationship.

Mansa Musa:

Right.

Alexia Pitter:

And so as time progressed, one of my best friends; her name was Jess; she came to me and she said, “You know, your dad’s been in there for 20 years. I have some organizations. We can come together. Let’s try to get your dad out.”

I remember just looking at her, being so confused. I didn’t know what to say, because I never thought that that was possible.

Mansa Musa:

Yeah.

Alexia Pitter:

To me, this was his existence, this was his home, this will always be his home, nothing else outside of that. I couldn’t really process that. So I was just like, “Sure, I guess. But I don’t even know where to start, what that looks like.”

After that, I decided to go the clemency route and I had different organizations working with me. And me and my dad had one of the most open, honest conversations that we ever had. I’m getting already a little emotional-

Mansa Musa:

Yeah, [inaudible 00:05:26]

Alexia Pitter:

… because what that looks like.

Mansa Musa:

Yeah.

Alexia Pitter:

Yeah, thank you. What that looked like was me, for the first time, not having to survive, and me learning that mentality. Because when I was younger, I think what I realized is that by me saying that he couldn’t come home, that it wasn’t possible. That was my way of protecting myself from disappointment and not getting my hopes up.

So when my best friend brought up this idea of him coming home, we did have to have that honest conversation. Because for the first time in a long time, I didn’t have to be the strong child. But I was allowed to say, “Honestly, I want you to come home, Dad. I need you to come home.”

Mansa Musa:

Yeah.

Alexia Pitter:

“I need you to be at my graduation. I need you to help me to become an adult. I need your advice. I need you to physically be there.”

And that was the toughest thing that I’ve ever had to go through, because I had to be honest with myself. It’s almost like when you have that wall up and you just have to let that wall go.

Mansa Musa:

Let’s flesh that out. Because see, that right there is the part of the conversation that most of us don’t get when we talk about the impact that this prison industrial complex has on family, and the impact that it has on children of the parent, the person that’s incarcerated.

Because you just outlined that, and you outlined early, your father had done some amazing things and educate you and gave you a sense of knowledge that made you the woman you are today.

But then you went on and expressed that psychologically, you had positioned yourself to say, “Well, my dad is never coming home and I got to find comfort. I got to find some way to rationalize that, because I want my dad home. But I don’t want to say nothing because I don’t want to create a disappointment.”

Alexia Pitter:

Yeah.

Mansa Musa:

How did you ultimately come to the point where you was able to process that? And as we know now, you are moving forward in terms of organizing and doing the things that would ultimately result in him coming home? I know that to be a fact.

Alexia Pitter:

Thank you. Thank you. No, that’s a great question. I say this a lot, especially as a Black woman: we’re so used to taking care of everyone around us.

Mansa Musa:

Come on.

Alexia Pitter:

And I would say my mom led by example. My mom had me at 18. She was kicked out when she was pregnant. I lived in Jamaica for quite some time. I came back.

And with my mom, no matter how much she was struggling as a single mother, she always said, “When we see your dad, I need you to put on your best-dress clothes. He doesn’t need to know that we’re struggling. He doesn’t need to know that we feel him not being here. He needs to know that we’re okay. He has enough to deal with. He needs to know that we’re okay.”

And so following that example, at a young age, that’s what I knew when I came to see him, I wanted to laugh with him. I wanted to joke with him. I don’t want to tell him about the things that I’m going through. He has enough going on.

And so for me to get into that transition, like I said, when my best friend told me, “Yeah, we can do this. This is a possibility.” I would even go as far as her saying, “I had a dream that your dad will come home.”

Mansa Musa:

Oh, yeah, right.

Alexia Pitter:

She was doing some other work in the community. And she’s like, “I feel in my spirit that it is my job to help you with this. I’ve only spoke to your dad two times, but I feel like this is in my spirit that I have to help.”

And being able to go through this clemency process: one thing we did leading up to the clemency process is we meditated and we fasted for, I want to say 15 days leading up to clemency.

We meditated at the exact same time. And we did journal prompts of, “Okay, what would happen when he came home? How would you feel?”

And we were talking to each other over the phone about it. He was just very emotional because I think in his mind he kind of put away the idea of being home as well, or not wanting to tell me that it’s a possibility, because he doesn’t want to get my hopes up.

Mansa Musa:

Right.

Alexia Pitter:

But I would say that was the first time that we were vulnerable with each other and allowed our deepest, darkest thoughts to come out.

And even to that extent, I want to say two days before his clemency, he told me on the phone, he said, “Look, I was trying to help someone. They were gang-affiliated and I was trying to be a mentor and I was trying to help them get them out of the gang. I’m trying to mentor them. And they died right in front of my cell, and there was nothing I can do.”

And he said, “Baby girl, I’m not okay. And I want you to know that I’m not okay.”

Mansa Musa:

[inaudible 00:10:41]

Alexia Pitter:

And I was able to say as his daughter, “I’m not okay.”

And I think that’s the thing that changed: is as much as he’s taught me so much, and as much as we’ve had these amazing conversations as a Black man and as a Black woman, for the first time there was a space where we were allowed to say that we were not okay.

Mansa Musa:

Yeah. Yeah. Yeah.

Alexia Pitter:

This prison system did affect us, that we did feel broken down. He even went as far to say, he was reading this book by Ta-Nehisi Coates, Something Torn and New, that talked about re-remembering.

And he said, “I think about what my ancestors went through. It’s hard to process, because although I don’t know exactly what they went through, I know what it is to be chained. I know what it is to not have my freedom. I know what it is to feel so locked up in this body, and I can’t breathe, and I’m suffocating.”

So I think to answer your question, that was that breaking point. We needed to be vulnerable. Because in this life, we’re taught that you can’t be vulnerable, that you’re vulnerable when you have time for it. You work, and then one day maybe you’ll have time for that.

So I hope that answers your question.

Mansa Musa:

Yeah, that answer my question. Yeah. And I want to flesh this out. 1), I told you I did 48 years in prison. The whole entire time I was locked up, this was my prayer. I could die on the other side of the fence, on the other side of the wall, but I refused to die in prison. I refused. This is what drove me. I refused to.

I don’t care if I went on the other side of prison and fell right out dead. As long as I didn’t fall out dead on the side there I was still held in captivity.

But the thing that I think that what you just outlined is how it’s hard for your father, or any individual in the prison industrial complex, on the plantation, to express any vulnerability. Because the system is designed to dehumanize you, demoralize you, and break you.

So the only thing that you have left George Jackson said in prison, let’s say, “The whole fight for them is to take our individuality. You take our individuality and you put us in a collective mentality, in a herd instinct. To everything we do, we do it in a herd instinct.”

So for you and this breakthrough between you and your father, to have this moment where; this is the part about the Father’s Day, and this is the part about the impact that the father have on the child and child on the father; to allow y’all to find a space where y’all could be vulnerable. And therefore allow his humanity to come out in a space where he could be human.

Because just like you saying, when y’all going on a visit, put your best face forward, wear your best dress. When he coming in there, he coming in like, “I’m putting my best face forward. I’m putting my best foot forward. I can’t let them know that somebody just died in front of my cell. I can’t let them know that they just put somebody in my cell and he got mental issues and it might be a problem. It might not be. I might have to do something to him or for fear of having something do to me.”

But what you was able to do; and this is the part I wanted our audience to recognize; is that when you talking about fathers and their children, the children and the parents, they make each other. They create that sense of humanity in that inhumane environment. Did you feel that?

Alexia Pitter:

Yes. Yes. I absolutely feel that. I do. That’s one of the things that I admire about our conversations now, especially as I get older, I feel more comfortable talking about how I feel. We push ourselves to be human, and allow ourselves to be human, and to laugh and to talk about things, but to feel.

And that’s something I realized too is I would say that when I recently spoke with him, I want to say about a week ago, I was on the phone with him. We have a book club; we are always talking about our books, and we read the same at the same time. But this time I heard something in his voice. And I said, “What’s wrong?”

He’s like, “It’s okay. We don’t have to talk about it, baby girl. We don’t have to talk about it.”

I’m like, “Mo, I want you to know that you’re able to talk to me. I may not have the answers. I may not know who to call. But I want you to know that if something is going on, you can talk to me the same way I want to talk to you.”

And he said, “Well, to be honest, I feel so guilty about not being in your life that I feel like for this 20 minutes on this phone call, the least I can do is hear what you’re going through and be there for you.”

And I said, “Well Daddy, you know we’re both doing that. If I’m doing that because I don’t want to stress you out, and you’re doing that because you don’t want to stress me out; well, now we’re just holding everything in. And the prison is winning in a sense.” And-

Mansa Musa:

And talk about this, Alexia.

Alexia Pitter:

Yeah.

Mansa Musa:

Not to cut you off, but talk about this here because I want these moments right here to be snapshots: to get people to understand the system, and the impact this system has on us in terms of our inability to be able to be in a space where we can have a normal conversation.

Talk about why you think this system is so caught up on, or so hell-bent on destroying … that right there, destroying any humanity that we have in us, mainly as it relates to why the system don’t have a mechanism where families can reunite?

Alexia Pitter:

Yeah.

Mansa Musa:

Why the system don’t have a mechanism where the father can have more access to the child in an environment where the child doesn’t feel like they have to suppress feelings and emotions, but can be able to express? Why you think this system is hell-bent on that?

Alexia Pitter:

That’s a great question. The best way I can answer that: I was interviewing a formerly incarcerated individual; I can’t think of the name at the moment. And I said, “Well, how did you know you were ready to be free?”

And he said, “Well, I had to be mentally free before I could ever be physically free.”

And the first thing I did, I was like, “I have to tell my dad this, because I found the key. I know what we have to do now. I know what the next step is.”

Mansa Musa:

Yeah.

Alexia Pitter:

I was very excited. And so with this prison system and the prison industrial complex, it’s not just what they say: “You do the crime, you do the time.”

Mansa Musa:

Come on.

Alexia Pitter:

It’s a psychological thing. They want you to feel small. They want you to not only be physically in chains, they want you to mentally be in chains. And what that looks like is not allowing certain books to come into prison. They don’t want you to learn too much. I tried to send my dad to Malcolm X books, and they turned that down really quick.

Mansa Musa:

Yeah, right.

Alexia Pitter:

They don’t want that.

The next thing is, as a family, when you walk in, you’re being searched.

Mansa Musa:

Yeah.

Alexia Pitter:

They’re touching you in places that’s uncomfortable. The correctional officers won’t even look at me. And especially because it’s a rural town, I’m spending three hours to see him. That’s about $100 in tolls, then paying for the vending machine.

And at this point, I’m mentally and psychologically thinking, “It is inconvenient to see my dad because I have to pay this much money. Because I have to be searched, right? Because I have to make this long trip.”

And him, they’re teaching him, “Well, you don’t deserve to be loved. You don’t deserve for someone to come to visit you. And if they do, it’s going to be on a two-hour timeframe. You don’t deserve to have these kind of discussions.”

They want him to psychologically continue to feel enslaved, to know that there is no other option. And they’re trying to teach him that he is defined by his mistakes.

Mansa Musa:

Yeah.

Alexia Pitter:

And I think that’s another thing that’s very specific: is when you tell someone your one mistake is going to define you for the rest of your life, how is someone ever going to think that they’re more than that mistake?

Mansa Musa:

That’s right.

Alexia Pitter:

How are they even going to process what it is to heal, or even that healing is possible? How are they going to know that they can do better?

And it causes this issue, this strong … taking a minute to process.

Mansa Musa:

Come on.

Alexia Pitter:

It makes us engage in the self-hatred and the self-destruction.

Mansa Musa:

Yeah. Yeah. This is hopelessness.

Alexia Pitter:

It’s hopelessness. And as long as you stay in that hopelessness, you’ll never come home. You’ll never see outside. You’ll never think outside of this mental slavery.

And that’s why I told my dad. I said, “Right now, I don’t know if Governor Pritzker is going to say you’re coming home. But what I do know is you have control over how mentally enslaved you are. So what we’re going to do, we’re going to read books, you’re going to learn about your ancestors.”

When we’re on the phone, I always say that on every 20-minute phone call for the last five minutes, I make sure I tell a joke to make my dad laugh.

Mansa Musa:

Yeah, right. That’s right.

Alexia Pitter:

I have to get his spirits up, and end every conversation with, “I’m proud of you.” Because especially as Black men, they don’t hear that enough. And sometimes especially as Black women, we’re having our own things that we’re going through.

Black men are fighting against society, we’re fighting against society. And by the time we come together, we’re just all over the place. And sometimes you need someone to say, “I’m proud of you.”

Mansa Musa:

Yeah.

Alexia Pitter:

And to bring that a little further, my dad’s mother passed away when he was very young. And he told me, he said, “I feel like you’re a reincarnation of my mother. And the reason I said that is because my mother was the only one that I felt believed in me.

“And here you go. I wasn’t at the graduation. I’m not there to physically walk you down the aisle when you get married. But yet you still show up for me, yet you still answer the call. Yet you still say that you’re proud of me.”

And he says all the time, “The reason that I knew that I could have a second chance is because you believed in me.”

And that’s the thing with the prison system. They don’t want them to believe that there is another option. And it creates this deep dark hole that brings you back to the 1800s-

Mansa Musa:

Have mercy.

Alexia Pitter:

… that brings you back to the 1700s-

Mansa Musa:

Have mercy.

Alexia Pitter:

… because you do identify with your ancestors. Because you know what it is to be enslaved, and you know what it is for you not to see family. You know what it is for you not to be able to read.

And that type of connection between your ancestral self and your enslaved self in 2024, that can create self-destruction.

Mansa Musa:

[inaudible 00:22:22]

Alexia Pitter:

And that is what their purpose is.

Mansa Musa:

Let me ask you this here. Because I know our audience probably are asking the same question, and it might be rhetorical for me.

Why do you believe in your father, despite the fact that he’d been incarcerated, left when you was three. But as you express your belief in him and your love for him, why do you have this for him in the absence of?

Because that’s the thing that it’s a two-way street, the parent on one side and the child on the other. But now we talking from the child’s perspective, the young woman’s perspective. Why?

You got all this passion about your father, despite the circumstances he find himself under. Why?

I mean, people want to know. Somebody would probably be screaming right now, “This is just a hopeless situation. Why she got this much respect and revere him so much in the face of all this that she has to go through, to even spend a couple of hours with him? All she has to go through to have a 20-minute phone call, all she has to go through to not be able to say, ‘Oh, let me call my father and tell him I’m going to be ready to do X, Y, Z.'” Why?

Alexia Pitter:

That’s a great question. My father, and like I told you, I never wanted to know why he was in prison. But I started to ask questions.

He migrated to America, I want to say, when he was 16. And when he came here, he didn’t have a visa and he didn’t have any way of making money. Then he found out he had a child at 18.

In his mind, he felt like, “I needed to do whatever I could do to make sure my child did not go through what I went through in Jamaica in poverty.”

So he became a part of a gang-affiliated organization and things like that, and just talking to the wrong people, being in the wrong spaces. And he made a mistake.

As I’m getting older; I’m from three years old to five years old, to 10 to 20; I see how he says, “Well, I’m going to meditate today. I’m going to journal today. I really want to know what is healing. I want to learn what it is to forgive myself. I want to understand, who was that little boy growing up? Why did he need love in all the wrong places? Why did he make these actions?”

He was asking himself these questions. It wasn’t for a six-month period and then we never talked about it again. It happened throughout my entire childhood.

And so now I’m at home and especially growing up without a father, I’m already a statistic. “You’re not going to make it to college. You’re not going to be financially stable. You’re going to end up in prison just like your dad.” That’s what I heard my entire life.

I’m in school and I’m struggling and it’s hard to keep up. I’m being bullied in school. I’m being physically abused. I’m dealing with sexual abuse, and I’m trying to process all these things as a child. And I’m still trying to make it to college, and I’m still trying to be the best that I can be.

And I had this moment and this understanding: “If my dad can be in chains, can be in this small room to use the bathroom in front of someone, for someone to tell him when he has to eat; if he can go years without medical treatment, without speaking to a therapist and still make the effort every single day to be a better man, there’s nothing that I can’t do.”

That is what he taught me at a very young age. And his strength and his determination and his willingness to always make sure that he is mentally free, no matter what is against him.

I knew. I knew. And he has taught me that there’s nothing that I can’t do. So when I fight for him, it’s not just fighting for him, I’m fighting for me. He’s a part of me. We are together.

Mansa Musa:

Right.

Alexia Pitter:

And I have to believe that. Because I will be honest: I’ve spoken to formerly incarcerated individuals. They even said like, “Hey, can you call my daughter, explain to her my circumstances?” And I absolutely do, because it’s just so much that he doesn’t have access to, and I have access to so much.

And if 20-something years later he can still answer the phone and still give me advice, despite someone dying in front of his face and still showing up for me, there’s no reason why I wouldn’t show up for him.

Mansa Musa:

And you know what?

Alexia Pitter:

To me, that’s community.

Mansa Musa:

And you know what? That’s the part of this process and the part of this experience, the prison industrial complex, the plantation.

I remember reading after slaves was freed, what they did, they put want ads in the paper. Ads were saying, “Do you know where Mary Jane or Betty Jo is at?” To find their family members to link up with them to go build a community.

But you just talked about how that’s done in the spirit world. This is the spirit that you’re talking about that got you motivated to stay in that space. But more importantly, this is the same thing with your father.

If somebody was to ask you about your father, how would you describe your father?

Alexia Pitter:

Where do I even start? First, every time he sends me a letter, it says, “Negus Gasi.” His name is Gasi Pitter. And “Negus,” for a lot of people who don’t know, is “King.” That’s what it means.

And so even in his letter writing, he always says, “You better write ‘Queen.’ I’m not answering. I’m not opening the letter unless it says ‘Queen Alexia.'”

So even in that way, he set the tone of what it is to step in a room and believe that you are enough, and hold a crown on top. And that was the thing that he’s taught me so much that really describes him.

He never makes excuses. To this day, he still feels guilt about the crime that he made. And he still mourns the losses of the victims in that circumstance. And he always says, “It’s not the mistakes that you make. It’s how you recover from it.”

Mansa Musa:

That’s right.

Alexia Pitter:

“What do you do? What do you do after you’ve made that mistake?”

And so to describe him, he’s very spiritual, he’s very grounded. I’m very jealous sometimes, because I’m like, “How in this world of chaos are you so grounded?”

Even when I call him, I’ll say, “How are you doing?” And his answer never changes. He says, “I’m peaceful.” And he always says, “That doesn’t mean that my environment is peaceful.”

Mansa Musa:

That’s right.

Alexia Pitter:

“I have found peace within myself so that I can exist in this environment for now.”

And so hearing these things, especially as a woman and hearing the adversity, he’s resilient. He manifests beauty. He pours so much love into the world, even when he didn’t receive love.

He mentors individuals that maybe he never talked to. But he sits down with them and he walks them through what he’s went through in life, and why you have to make a difference.

And then he always connects it to the ancestors. “They’ve worked so hard so we can be where we are. So we have to do better. We have to pay our respects.”

He’s very spiritual and he loves to laugh and he makes jokes. And it never feels like he’s my father. It just feels like that’s my best friend.

Some daughters don’t want to tell their parents certain things. That’s not the case. Sometimes we tell each other too many things and it’s like, “Okay, slow down.” But no, he just represents light and love.

And he really taught me that, “Just because you didn’t feel loved at a point in your time doesn’t mean you need to give love. In fact, it is your job to give even more love to make up for the love that you didn’t receive.” And to me, that’s the best way to describe him.

Mansa Musa:

As we close out, if somebody seen your father and said, “King, describe Queen Alexia to me. How is she?” What do you think he would say?

Alexia Pitter:

I’ll be honest. He just told me this. He said, “I don’t think you truly realize the power that you have.”

He describes me as a warrior with a lot of battle scars, and he describes me as resilient. He believes that I give a lot of love to this world, although I may not have felt a lot of love.

He describes me as a leader and someone who’s always, always going to tell the truth and show up as my authentic self despite where I am. And a lover and a forgiver and a mentor. I love to mentor people, and I learned a lot from him.

But then also I would say a person of community. Community is very important to me. I always try to surround myself with community and always giving back.

So I think he would say that I’m the nuclear system of each community that I go in. I bring people back and I help ground others. And I think that’s the best way he would describe me.

Mansa Musa:

Let me ask you this. How can our audience and our viewers get in touch with you? We know that you’re doing the clemency, y’all working on the clemency. How people can get involved with your effort to get your father free? Or more importantly, any other work that you’re doing?

Alexia Pitter:

Thank you. That’s a great question. We have a petition right now on change.org. If you just type in Gasi Pitter, G-A-S-I P-I-T-T-E-R, you can sign the petition.

Also writing a letter to Governor Pritzker and saying that he does deserve to come home; he is a changed man, and that he will have support when he comes home. So sending those letters are important.

Then you can also email me at A-P-I-T-T-E-R @ famm.org, F-A-M-M.org, and share what you thought about today’s podcast and just what you think in general about second chances. Those are probably the best ways that you can support us in our journey.

And just always continue to fight for prison reform, and know that people are humans outside of the crimes that they’ve committed. He was 18 when he committed this crime. He’s now going to be, I think, 43 years old. That’s a large amount of time to make a difference.

So really just open up your hearts and minds, and turn away from what you’re hearing in the media because everyone is not bad. In fact, there’s a lot of people who come home and do so many things for the community.

And because they’ve been through that similar thing, they know exactly what to say to the young people coming up. And so just really thinking about that. That’s the best way you can support me and all the other people waiting to come home.

Mansa Musa:

There you have it. The Real News, Rattling the Bars. We just got finished talking to Queen Alexia.

And I would like to offer this point of view. If someone was to ask her father what did they think of her? He would say, “Here come the Queen, because she’s definitely representing her father.”

This is about Father’s Day. But more importantly, this is about humans, human beings. Alexis is a human being. Her father’s a human being. We got 2.5 million people that’s incarcerated on these plantations that are human beings. And we got a society and a system that says, “Despite your humanity, we’re going to do everything to take it away from you.”

But we have this storyteller today telling us, no, that’s not the case with her father. And that’s not the case with her.

Thank you Alexia-

Alexia Pitter:

Thank you.

Mansa Musa:

… for coming in and joining us today.

Alexia Pitter:

Thank you.

Mansa Musa:

And we ask that y’all continue to support The Real News and Rattling the Bars.

Rattling the Bars is here to give voice to people like Alexia and her father. Rattling the Bars is here to give voice to the voiceless and The Real News. Well, as we always say, because we are actually The Real News.