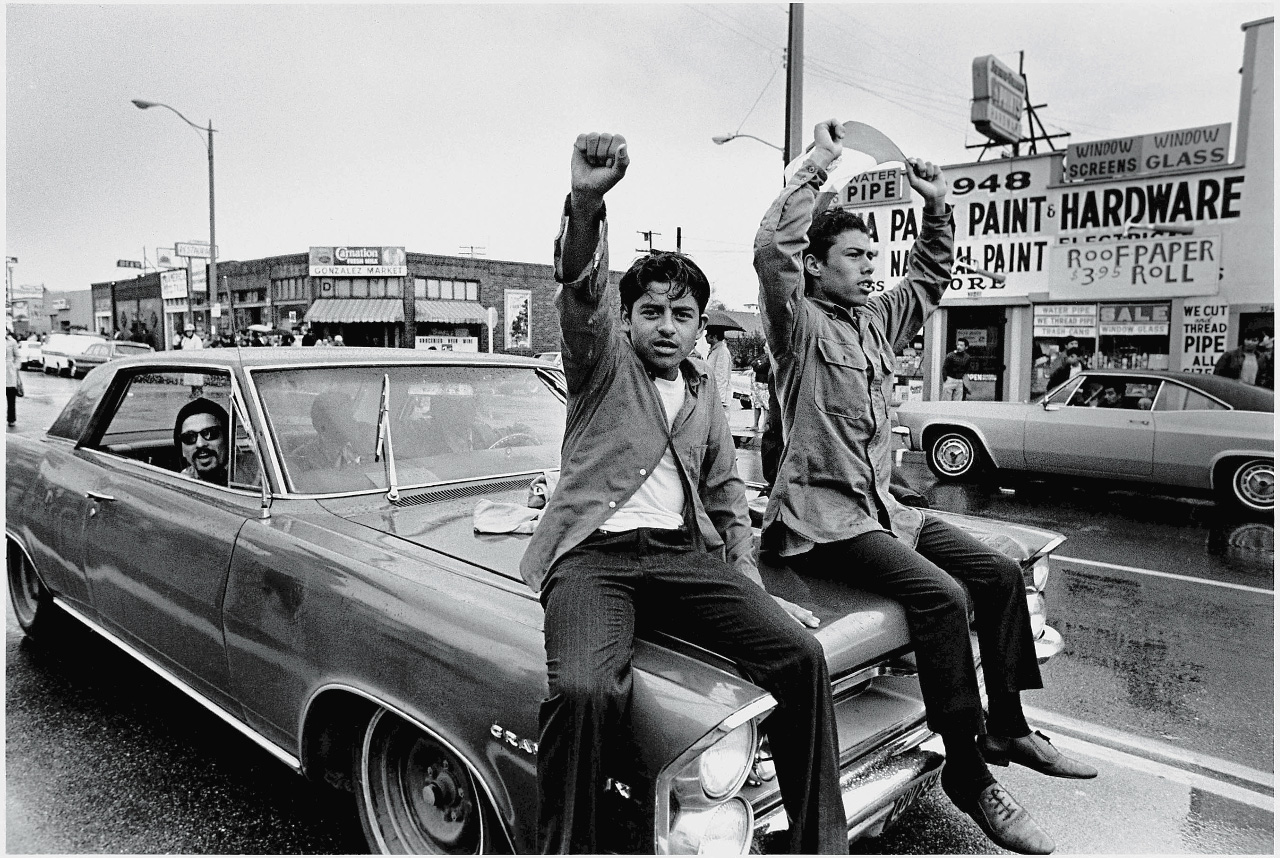

On August 29, 1970, the Chicano Moratorium Against the Vietnam War mobilized the largest Chicano protest and the largest anti-war protest led by a community of color at the time. Combining a critique of US imperialism abroad and racism at home, the Chicano Moratorium was the result of years of organizing and consciousness raising by Chicano liberation activists around the country. Former Brown Beret Bill Gallegos and CSU Northridge professor Theresa Montaño join The Marc Steiner Show for a look back on the Chicano Moratorium and the struggle from which it arose.

Studio: Cameron Granadino

Post-Production: Alina Nehlich

Transcript

Marc Steiner: Welcome to The Marc Steiner Show here on The Real News. I’m Marc Steiner. It’s great to have you all with us.

54 years ago, on Aug. 29, 1970, the Chicano Moratorium against the Vietnam War took place. More than 25,000 people marched, and at that time, it was the largest Chicano mass action in the history of its resistance, and one of the largest anti-war actions that took place, period. It was a mass peaceful protest that was violently attacked by the Los Angeles police, who killed four people, injured hundreds of others.

People took to the streets because 20% of all the troops killed in Vietnam were Latino and Chicanos, and they bore the brunt of the police brutality working for poverty wages and faced massive discrimination — I shouldn’t say that in the past tense. It still exists.

Today we broadcast the first of a two-part series on the Chicano Movement, then and now. My co-producer who came up with this idea is Bill Gallegos, who’s a long-time activist who worked with the Crusade for Justice in Colorado and was a member of the Brown Berets in California and the author of “The ‘Sunbelt Strategy’ and Chicano liberation”.

And we’re also joined by Theresa Montaño, who’s professor in the Chicana and Chicano studies program at California State University at Northridge, was a leader of the California Teachers Union, a long-time Chicano activist who was also there on Aug. 29 at the Chicano Moratorium against the war.

So welcome to you both. It’s great to have you both for this. I was looking forward to this.

Bill Gallegos: Thank you, Marc.

Theresa Montaño: Great to be here.

Marc Steiner: As I wrote to you earlier, Bill, I’d like to begin by getting a feel for that moment. You wrote a really beautiful poem about the moratorium. Could we start off with that just to give a sense, a poetic sense of that moment in that time?

Bill Gallegos: Absolutely. This is called [Spanish], “The Chicana Moratorium, The Fire that Never Dies”.

Waves crashing through the streets of a hot and smoggy barrio. Thunder, thunder, pounding along the shoreline of poverty, [Spanish], an ancient sound, a holy sound, [Spanish]. We will die for you no more. Our blood will no longer flow for bankers and crooks. Our flesh will never again rot for the pitiful dreams of stolen wealth.

We will continue to die, but we will die in a noble way. We will die fighting you. 25,000 of us say, “Hell no, we won’t go,” but we will stay and fight you. We will sacrifice our youth, [Spanish] to fight you, to build on your ruins something beautiful, untouched by your corruption. [Spanish] a new prayer, a new song, a new poem, a new dream for our homeland, [Spanish].

Don’t call me wetback. Don’t talk about spics, beaners, and dirty Mexicans. Don’t tell me about my place. This is our place, our barrio, our [Spanish], our [Spanish], racist earth destroyer, dying boss of a dying empire. You better watch yourself here, 25,000 in a moratorium against your war. We will fight you to the death.

The toilers, seekers of knowledge, creators of art, the youthful future of our people, experienced teacher of past generations, all, all, we will all fight you. [Spanish]. You attack. 2,500 cops sent to kill us. Mindless, they shoot, kill, maim, burn, march on the dignity of our [Spanish].

Yes, you did murder four of our sons, Salazar, Ward, Diaz, and Montag, but look how they rise from the grave. Watch their faces in the thousands who throw stones through your cowardice, who torture, ragged inhumanity. Can you see their somber warning as they live again? Can’t you see the outlines of their souls in the flames, which raise bold tongues to heaven? The moratorium, la moratoria, the fire that will never die.

Marc Steiner: Thank you, Bill. And Theresa, I want to talk about that moment. The moratorium came on the heels of two years before when the Chicano students walked out of high schools across Los Angeles and this massive movement. Paint a picture of that moment for you then for people who have not heard of it, for our listeners who don’t know about it.

Theresa Montaño: It was a momentous demonstration for many of us. I was very, very young, and coming into a collective consciousness of the importance of becoming Chicana, of Chicano liberation. I actually snuck to the moratorium, telling my mother I was going to go do some shopping [Steiner laughs]. I knew she would never agree to go or to have me go.

It was very hot. There were a number of people that were going to communities outside of East LA. We were taking the bus to the park. And lo and behold, there drives up some members of the Chicano Moratorium committee and asked us if we were going to the moratorium, and we said we were, and they drove us there.

I’d been to a few demonstrations before that, but never in my life have experienced a demonstration of this size, of this many people, of this many people who look like me, who felt like me, who were as angry as I was, who were as conscious about our justice movement in the US, for justice for Chicano people here.

The right to an education, the right to Chicano studies, the right to employment, the right to see our brothers and our sons and our husbands come back here and fight the war against aggression, and the consciousness that it was not an enemy abroad that we had to be fearful for or that we had to fight against, but that we had to really think about who the real enemy was.

It was a tremendous moment. We were all sitting in the park and join the festivities, the [Spanish], the speakers. I had friends who had never had any consciousness, were just curious, so they came with me.

At the moment when the police began to charge the demonstrators, we were towards the front of the program, so the stage. We had no idea what was going on. They were just charging at anybody. One of my friends got hit by a billy club on her left shoulder, and at that point people just kept saying, don’t run, don’t run, walk, walk. And so we went out of the park. People who were not at the demonstration opened their doors and told us to come in, come in, get water, come in [for] safety.

And so we had no idea what was going on outside after that. We had no idea that Ruben Salazar had been killed and that people had been arrested. But I think we did have a renewed idea about who our enemy was and what we were fighting for.

And Bill, I gotta get that poem from you. When you were giving it, it hit me right at my heart. It really brought back memories of that day.

Bill Gallegos: Thank you, Theresa.

Marc Steiner: One of the things I think is important for people listening to us to understand at that moment is when people think of the ’60s, when people think of what went on in America, Chicano people are always on the periphery, or never thought of at all.

And even when you look at the anti-war history that took place in the ’60s, we read about the Panthers, we read about SDS, we read about the mostly white movements that took place as well, but the Chicano movements were like given a… Nobody paid attention. It was like the othering, it was like a massive othering.

And this explosion that happened in this demonstration and the students walking out two years earlier from high school in that massive protest against racism against Chicano kids. Let’s talk about that for a minute because I think, Bill, it’s something that we don’t think about often enough, that we don’t dive into the depths of what that means.

Bill Gallegos: Yeah, Marc, I’m really glad you brought this up. I’m particularly critical of the US left because I know that the power structure, the white power structure is this is how they work, this is how they do. But the US left is also at fault for this.

There’s very little study at all of the historical and political significance of the US annexation of Mexico’s northern territories, which enabled the United States to become a superpower, the superpower that it is today, and what happened to the people, the Indigenous and the Mexican people who were conquered in that annexation, and what was the impact on Mexico, on the United States, and on those peoples.

So that’s why so much I appreciate The Real News Network, because there is a voice for this incredible liberation movement that is over a century-and-a-half old.

And the moratorium was significant in so many ways because there was no other ethnic community, no other oppressed community that had anything like this during the Vietnam War.

There were over 20 moratoriums against the war that reflected our internationalism, connected it to our fight, as Theresa said, to our fight here at home for our national rights and our self-determination and for full equality. There was nothing like this. It’s a very unique and important event in history.

And the Chicano moratorium in Los Angeles at that time, as Theresa said, was the largest mass action we’d ever had. And it was overwhelmingly working class, but organized by revolutionaries. Socialist, communist, revolutionary nationalists, Gloria Arellanes and Las Adelitas De Aztlán, very militant feminist organizations, when their people weren’t even using that term.

And it demonstrated that the ideas of this sector, this revolutionary sector of the Chicano liberation struggle, had resonance among the working class of our communities, because this event was overwhelmingly working class. It brought together all sectors. There were students and academics and professionals, but overwhelmingly it was campesinos and factory workers and domestic workers. That’s who was there at this.

And it demonstrated that the ideas of the left, the ideas of the Crusade for Justice and the Brown Berets and the Communist Party and Los Siete de la Raza and all of that had resonance among our people. It had that strong impact among our people, and that really scared the white power structure.

There’s a book by Seymour Hersh about Henry Kissinger, it’s called The Price of Power. And he talks about how the Nixon White House freaked out when the moratorium happened. They freaked out because they said, we thought we had the Mexicans in line. We thought we had them under control. They all joined the military. They’re all going into the military. And they said, we expect this from Black folks. We didn’t expect it from the Mexicans [Steiner laughs].

So it really, it had an impact, and for a minute, it caught the attention of the world, that we had a freedom struggle, that it was a long-standing freedom struggle, that it was still alive. As Theresa said, people were not out there just against the war and in solidarity with the Vietnamese people, because that was really significant, but also connecting it to the push out rate in our high schools, our lack of political representation, restriction on our voting rights, the loss of our land, police and [Spanish] brutality, the suppression of our language and culture, all of those issues became highlighted as part of our freedom struggle.

And this was really significant. It demonstrated that our movement was not just a kind of liberal movement for integration into the existing order, but it was a national liberation movement. That was very, very significant, in my opinion.

And I fault the US left largely for ignoring this question. They still frame everything in terms of Black and white. And of course, Black folks have had to fight for that recognition, and they should be, that freedom struggle should be acknowledged, but so should ours, so should that of Asian Pacific Islanders and others. So I’m really glad that we’re doing this because there needs to be more of it.

Marc Steiner: There needs to be a great deal more of it. Theresa, you and your peers, when this happened in LA, what I remember — Not being there then, I was on the East Coast, not the West Coast — But there was also this student movement, the student protest that took place in ’68, where thousands of Chicano students walked out and had these mass demonstrations. And sometimes I felt like there’s an arc between that and the moratorium.

Theresa Montaño: Definitely there is an arc between that and the moratorium. I think that the idea that we had student walkouts in ’68 and then in the moratorium in 1970 and nothing in between is a fantasy [Steiner laughs]. There was a lot going on. And I link it to some of the issues going on today.

In 1968, what students were demanding was the right to be seen, the right to self-determination, and the right to quality education. So they were actually saying, we have a really messed up educational system on everything from — And I was a part of the walkouts in ’70, so it went all the way through to the moratorium. ’68 —

Marc Steiner: Can we get back one second? I didn’t mean to interrupt, but so it wasn’t just in ’68 when the high schools [crosstalk]?

Theresa Montaño: No, absolutely not. It was ’68, ’69. There was a moratorium in February in the rain. In 1970, there was a repeat of the 1968 demonstrations, not only in East LA. I lived in South LA, and there was a walkout at my high school demanding the same thing: We want to be seen, we want the right to determine our real story and our truth in the US history books. We want to be treated with dignity, not punished for speaking Spanish. We want the right to go on to higher education.

These were all political issues that we were fighting for, along with — And I always have to say this — Along with an end to the war in Vietnam. So there was never a break between either of them. Our work for justice was connected directly to the end of the war in Vietnam.

Marc Steiner: I want to come back to some things you said, but I want to pick up on this last thing you just said, because I think people don’t realize the numbers of Mexican-American men who died in Vietnam. It was huge. It was like 20% of the people killed in Vietnam, way beyond the percentage of people at that moment who were Chicano in this country. People don’t realize the sacrifice, what happened, the working-class kids drafted and killed in Vietnam, who came from your neighborhood.

Theresa Montaño: Right. My neighborhood, neighborhoods in Texas, neighborhoods in New Mexico, and in Colorado. And that’s not just then. The other day I’m walking through the airport with a friend of mine who does ethnic studies work with me. And we were watching as an airplane was letting… Folks were coming out of the airplane, young men, soldiers. Every single one of them, every single one of them was Brown.

So this is not just something in the past, this is something in the present. And it’s scary. It’s scary because of the role that this country is playing in the world today. I’m afraid that this may happen again.

Marc Steiner: Bill, I know you’re dying to jump in on that one. Go ahead.

Bill Gallegos: Well, it’s just, there’s a long history of our people going into the military because there was the illusion — And it’s understandable — That this was a pathway to equality and social mobility; We will be accepted. And it was proven, and the outrageous casualty rate that we suffered in Vietnam was one proof of that.

I just had a primo, a cousin of mine passed who served two tours in Vietnam, and he died because of exposure to asbestos on the ships that took those soldiers out there to Vietnam. And there was no disability payments for that. There’s no recognition by the United States that they murdered all these soldiers who were sent out on those ships.

So this is a consistent theme throughout our history is our effort to really break down all of the structures of oppression that were put in place after annexation: segregation into barrios, segregated schools, lack of voting rights, lack of political representation, loss of our land, all of that after the United States annexed Mexico’s northern territories. Its consolidation for US capitalism was to create all these structures of oppression that continue in some form today.

And so when Mexicanos come over, when they cross the border over here, the overwhelming majority of people that cross the border live in our historic areas of concentration: Texas, New Mexico, Arizona, Colorado, California. That’s where most people go. And they assimilate right into the barrios, right into the same poor jobs, right into the same poor schools, right into the same problems with mass incarceration and police brutality and [inaudible] brutality. They are assimilated into our reality, the reality that was created after annexation.

And that’s what gave rise to this remarkable resistance struggle that every student should learn about. It’s a struggle for democracy, for equality, for all the values that we hold as human beings, the humanistic values we hold that should be applied to all people. As Theresa said, dignity and respect.

Those sound almost like cliches. But when you’re treated like children, when you’re treated as disposable. Theresa and I, I think I shared this story with you, Marc, about our friend Ivan de Los Santos, who was a child of campesinos in Ventura County, just north of Los Angeles. And when those planes came over and we’re spraying all those herbicides and pesticides, this yellow cloud, the kids didn’t know what it was. They would run outside and chase the clouds, chase the planes. Look mommy, look mommy. They were poisoning us, and they do that to this day, to this day.

So this has given rise to this remarkable resistance struggle to the Crusades for Justice, to the Brown Berets, to the Alianza, to the United Farm Workers Union, to MEChA, to UMAS, to the Chicano Press Association. People don’t know that we… Because the media either ignored us or treated us in the worst, most stereotypical ways, we had to create our own media. And there were over 300 affiliates to the Chicano Press Association, over 300: El Grito del Norte, El Tecolote, El Gallito, all of these remarkable expressions of our reality.

And so I think I see it, as I’m in my golden years, one of the things that I really want to focus my life on is helping people to recognize and honor this remarkable resistance struggle, this remarkable freedom struggle.

And if we look at it just in terms of electoral politics, the Democrats would not win without our votes in California, Arizona, Nevada, Illinois, Colorado, and New Mexico. What would the Congress look like? What would the Senate look like? Who would be in the White House? That is very rarely acknowledged.

Because our resistance struggle, we fight in every arena, whether it’s cultural, or whether it’s strikes, and whether it’s at the level of academia where Theresa’s fighting, has been leading a struggle for the teaching of history in our public schools, an honest and genuine history of ethnic studies in our schools. And she has been fought tooth and nail in this battle even before there was the term, the racist term critical race theory, Theresa was fighting a battle for the true expression of our history in the schools, and the moratorium being one element of that history that’s ignored.

Marc Steiner: Theresa, I’m going to pick up on that point with you. And as we do that, I want to say the four names of people who were murdered by the police in that moratorium against the war in Vietnam: Lyn Ward, Angel Gilbert Diaz, Gustav Montag, and Ruben Salazar.

Theresa Montaño: Usually when we do our curriculum, we always add an ancestor acknowledgement. So as you say that, the word that comes to mind is [Spanish]. And Bill is right. I’ve been involved in the struggle. And I don’t think people recognize that the struggle for ethnic studies in California is much more than a struggle for diversity and inclusion. It’s not a diversity and inclusion struggle. It’s a struggle to get the truth told. Like Bill said, to have our story.

And in this particular case, it’s a broad-based coalition of Black, Chicano, Palestinian, Asian American, white, Jewish, and others who are coming together to fight for the authenticity of ethnic studies as a viable and academic discipline, but also to tell our stories.

And from day one, before the curriculum was approved or signed into existence, we received resistance. And resistance on what? Not resistance on teaching food, fiesta and [Spanish] and telling the stories of heroes of astronauts and others, but it was because we dared to talk about settler colonialism, because we dared to talk about — And this was prior to Oct. 7. It’s only gotten worse since then. This was prior to Oct. 7.

When we stood together in that room when our Palestinian sister said, hey, there’s nothing on Arab American studies in here. We need to add it. And we said, there’s nothing on Central American studies. We need to add it. And so we sat in that room the last few days, anxiously putting this in, only to be told that you can’t mention the P-word in K-12.

Marc Steiner: Told by whom?

Theresa Montaño: Told by the state, by the state of California. They took it out, they took the lesson plan out. And like I said, to this day, as I sit here today, tomorrow, they will be debating in the Senate Appropriations Committee in Sacramento whether or not they can add teeth to language that will make it easier for teachers to say, let me concentrate on your feelings as you take this ethnic studies course. Let me make sure that you don’t talk about Palestine. Let me make sure that you don’t write settler colonialism into the curriculum.

Now, you heard Bill’s story of our history. As I talk to politicians, they’ll tell me, yeah, that’s true. I don’t understand how you could teach Chicano studies without talking about settler colonialism.

But the fact is they are not worried about how white students will feel. They are worried that white students will wake up along with the other students who take ethnic studies courses and say, whoa, why wasn’t I told this truth?

And that’s why this small movement for ethnic studies is much more than a movement for a course. It’s a movement for the story of people’s struggle for liberation. And for stories to tell the stories of the four people you mentioned, plus hundreds of other martyrs, not Chicano, but Asian and Arab American and Black in this country who fought for their people’s rights as well.

Bill Gallegos: That’s right. People don’t know, Marc, that the last mass lynching in California took place near Olvera Street in downtown Los Angeles, and I think it was 19 Chinese immigrants that were lynched right there near downtown Los Angeles. So there’s blood and glory in the resistance and in the history of all of the oppressed peoples in this state, and it needs to be told.

Marc Steiner: There’s so much here. I could spend the next two hours, three hours [laughs] just to talk about all the things you all have just raised. But I’m going to come back to 1970 for a moment to bring us up to where we are. And what you both have just described has been the literal whitewashing of American history, of who we are as a people, as a nation.

Talk a bit about how you see what happened in 1970, the moratorium, and what happened before that in ’68 when all of the Chicano students walked out of those high schools across LA, and how do you think that changed the nature of the movement, the nature of the struggle, and what it led to? Because we don’t talk about those two things, but there were seminal moments in the history of struggle in this country among students.

So Theresa, go ahead.

Theresa Montaño: Well, I think one is it led to the institution — And I don’t know, it was a great victory, but it was also one of continued struggle — Of Chicano studies in our institutions of higher education developed for and by members of the Chicano community, developed through the Plan de Aztlan, which was, again, a group of revolutionary students and scholars who laid the foundation for Chicano studies. We now have celebrated more than 50 years of the discipline.

I think, again, it was more than just a day. It wasn’t a moment. It wasn’t a moment in history. It was significant for us, but it was a part of a larger movement that created an even bigger movement that led to a number of initial rights in education. We had more students enter colleges and universities because we opened up the doors. We literally knocked down the doors to institutions of higher education for Chicano students.

We changed the course of educational history in the sense we went from being punished for speaking Spanish to demanding the right to have a bilingual education with teachers who look like us and counselors who could counsel us. We fought for the right to representation in political office.

So that particular year, or those years, I have to say, led to a reawakening of the Chicano people that I don’t think we’ve ever seen since then, in the sense that we began to recognize that we were an oppressed and marginalized people, but we were not victims of that oppression, that we were going to stand up, and that we were going to resist that oppression.

And I think that, in a different way, is still something that I know resonates with my students. And I teach Chicano studies, so granted, the student that comes into my course, they’re at the very least curious, at most committed to social justice.

But I think that’s what it led to, an understanding that this is where our struggle is, here in this part of the United States, in the land that was taken from us. This is who we are, this is our legacy, and this is where we’re going to stay and continue to fight.

Marc Steiner: Bill, I know you had something you want to say to jump into that.

Bill Gallegos: Well, I just say, I think Theresa really captured it all, but it had such a broad resonance because before the Chicano liberation struggle of the ’60s and ’70s, you could count the number of our academics and intellectuals on one hand. We had no intellectual strata, we had no inteligencia, and it was different from the Black freedom struggle where they created their own colleges and universities. We didn’t have that similar experience.

So we had to knock down the doors of the existing institutions controlled by the white power structure. And that was huge. That was huge for opening up the possibility not only for our young people to learn and to advance, but also to really fight for our history to be told and our reality to be told in those colleges and universities. So that was really significant.

And also, I think the moratorium also created the sense that we are a movement, that it wasn’t just the United Farm Workers, that the United Farm Workers was about workers and about labor rights, but it was about the broader question of Chicano equality and freedom.

The Alianza in their fight for the land rights in Nuevo Mexico, it was about [Spanish] and [Spanish] and all that land that had been taken away. But it wasn’t just about our wanting the land so we could grow some chiles and [Spanish]. It was about really wanting our national rights to be honored and accepted.

My family ended up in the coal mines and the railroads. We were farmers! We ended up in coal mines because our land was taken away. And that happened to hundreds of thousands of us.

So the movement that the farm workers, the blowouts, it was a youth-led movement that blew out of these high schools, but it inspired every generation of the Chicano people, mothers and fathers and grandmothers and grandfathers. It opened up space, so much space for us.

And a lot of this came together in 1972 when there was a national conference of the La Raza Unida Party that brought together the Alianza, the Crusade, La Raza Unida Party, the Brown Berets, the United Farm Workers. It brought together all of these sections of our movement, and they adopted a program. If you ever look at that program that was adopted by La Raza Unida Party in 1972, it was a really far-sighted, progressive program; internationalist, rooted in workers’ rights, women’s rights, the right to our land, the right to democracy.

So I think this particular freedom movement, which now we number almost 40 million people, and we’re situated in critical areas of the US economy and US politics. So I think this is the idea of the spark that history can have on us, it’s still a flame, it’s still there, and it still can resonate.

And I think that’s why Theresa is fighting so hard, because she saw what it did to her. She felt as an individual how it liberated her. I saw how it liberated me, and it liberated my parents, liberated my parents. All of a sudden, the things that were just talked about in four walls became public conversation, big political conversations that were going on about how we were treated, what we had contributed to the development of this country and that was never acknowledged.

So I think this idea of celebrating these kinds of events like the Chicano Moratorium Against the War is so significant. It’s significant for us as a people, but it is significant for all working and oppressed people. This belongs to all of us. This is our collective tradition of resistance and fight for a society that is truly humane, just, democratic, that’s not controlled by 1/10th of 1% of mostly white men. I think that’s the seed of these struggles in events like the Chicano Moratorium. It’s about envisioning, in that fight, envisioning a new world.

Marc Steiner: And Theresa, as we close out, taking us back to that moment in 1970 and how transformative it was for you and the others in that movement, in that protest, and as Bill was saying, and what it gave root to, what exploded after that in terms of consciousness and the movement.

Theresa Montaño: Well, again, I have to say that the transformative moment for me were those years. Without a doubt, that Chicano Moratorium probably did the most significant heart work for me in the sense that I was able to witness one of the most historic moments in our history. But I have to say that it was that time during the building of the Chicano Movement that had the most profound impact on me.

And as I teach my students, we always talk about what did Chicano studies do for you? And I think that Chicano studies is living, and I always say that to my students. It’s living, it’s dynamic, it’s the everyday. It’s not what you teach in a classroom or what you read in a book.

And that’s what the Chicano Moratorium was for me. It was Chicano studies in the real. It gave me purpose, and I really have to say, gave me purpose, because from that moment, I knew what I was going to do in life. I was going to go to college, ignoring what everyone ever said about who can enter college and what college you can go to. I knew I was going to enter to teach, and to teach the story of my people in a way that had been ignored and basically suppressed.

And I knew I was going to continue to this day, where I am now, to continue to fight for that for others, for future generations, for the seven generations behind me. It was more than just a day in the hot sun where we stood up and fought against the war in Vietnam. It was an awakening, it was a call to action, and it was a call to the lifetime commitment for social justice.

Marc Steiner: That’s really powerful. And I think that one of the things that I think about as I was going back through all this stuff, and I remember that moment in 1970 when this happened. I wasn’t there, I was on the East Coast. But I remember it. And I remember that it was deeply significant because, A, it was the explosive nature of the beginning of a Chicano movement that was really critical to ending the war in Vietnam, sitting in solidarity with all the Chicanos who were stuck in Vietnam dying and being hurt, and the horrendous nature of that day.

People I knew who I lived with in Resurrection City who were hurt in that demonstration when the police attacked. And I think that it was one of the greatest acts of absolute, utter racism on the part of the LA police, and a vicious attack on peaceful demonstrators to say no to the war in Vietnam and no to discrimination and racism against Chicanos. I think it was one of the most important days that we don’t even remember.

Bill Gallegos: Marc, there’s a great film called Requiem-29 about the Chicano martyrs. It’s a great film.

Marc Steiner: Yes, I watched it last night.

Bill Gallegos: So this was an army, this was 2,500 police. And they said, well, we heard that there was someone jacking up a liquor store. So you send in 2,500 cops [Steiner laughs] to make sure they don’t grab the Colt 45.

So they murdered those four people, but in the initial assault, people didn’t run. There’s rocks, there’s bottles, there’s sticks, and you see this whole phalanx of cops backing up. And this was everybody. This was abuelitas, this was kids, this was everybody.

So it just gives a sense of the kind of courage, the kind of ethics, the kind of deep-seated anger, really, but also our belief that we are entitled to be treated as human beings. We are entitled to be treated with respect.

And that scene is just amazing because you see all these cops with their shields and their helmets and their clubs and their shotguns just kind of retreating in the face of this counterattack from our people. And I’ve always loved that scene in the film.

Marc Steiner: Yeah, it is an amazing film that we can attach to. People can watch it. I think it’s important, it’s important for people to see that.

And Theresa, as we close out, it’s a personal political question. Being in the midst of that madness when police are attacking, people are being beaten, it must have been, A, deeply frightening, because I’ve been through that myself, but also transformative politically.

Theresa Montaño: The other thing that I think helped us is that those of us who were standing in front actually saw that line, Bill, as protecting us as well, because as they were advancing, it gave the rest of us time to try to get away. It was really… We were separated. There were families that were there. I was there with a couple of my friends. As the police moved in, everyone scattered, so you didn’t know… And like I told you, I had friends that were… I saw being hit with billy clubs. I didn’t know whether they made it out of that crowd OK or whether they didn’t because I lost where they went. We all just went in different directions, scattered everywhere.

But I think the transformative part for me was the collective care that came from the community, I mean, like I said, people were… They didn’t know you, they didn’t know who you were. They said, come over here, come over here. This is where you’ll be safe. Open the door. Here’s water to put, because there’s tear gas all over the place. And I knew in my head, intellectually, I understood what police brutality was like. I had never witnessed it in such a massive, destructive, and awful way.

So it opened my eyes to the hatefulness that comes from the state and to the care and the beauty that comes from the community. I don’t know how else to describe it. People let us stay in their houses for hours because you had no clue when it was going to end, when it was going to subside, when it was going to be safe to go outside and not be stopped by the police.

I don’t know how I got home that night. I can’t remember to this day, how did I get home? Someone must have given me a ride somewhere, because I know the people I went with were not the people I went home with. And my mother knew where I went, so she was scared. It’s making me tear up. She was scared to death about what had happened to me, or if anything had happened to me. She didn’t yell at me. She didn’t scold me. She was just glad that I got in.

So I left home curious, awake, I was conscious already by the time I went to the moratorium. That’s why I went. But I came home transformed. And to this day, it is probably the most significant, massive demonstration that I’ve been to in my entire life, and I’ve been to many. I would’ve to say it was one of the demonstrations that made me who I am today.

Marc Steiner: Powerfully said. And I’m really glad we had a chance to meet and that you joined us for this conversation, Theresa. Theresa Montaño, thank you so much for being with us today. And Bill Gallegos, thank you so much for being with us. And Bill and I will be presenting another conversation in the coming weeks, and we hope you look forward to that. And thank you both so much for being with us and for joining us here at The Real News on The Marc Steiner Show.

Theresa Montaño: Thank you so much [crosstalk].

Bill Gallegos: Thank you, Marc. Thank you, Real News. Thanks, Theresa.

Theresa Montaño: Thanks, Bill.

Marc Steiner: Once again, thank you to Theresa Montaño and Bill Gallegos for joining us today. And thanks to Cameron Granadino for running the program, audio editor Alina Nehlich, Rosette Sewali for helping to produce The Marc Steiner Show, and the tireless Kayla Rivara for making it all possible behind the scenes, and everyone here at The Real News for making this show possible.

Please let me know what you thought of what you heard today, what you’d like us to cover. Just write to me at mss@therealnews.com and I’ll get right back to you.

Once again, thank you to Theresa Montaño and Bill Gallegos for joining us today. And we’ll be bringing you another installment of this conversation looking at the Chicano Movement today with Bill Gallegos and other guests. So for the crew here at The Real News, I’m Marc Steiner, stay involved, keep listening, and take care.