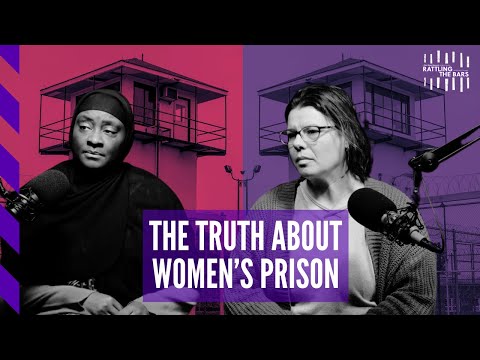

For decades, prisoners’ rights advocates have called on the State of Maryland to address its flagrant discrimination against prisoners housed in the state’s sole women’s prison. As The Real News has previously reported, conditions in the Maryland Correctional Institute for Women are akin to “torture,” and the lack of resources and services dedicated to incarcerated women amounts to state-sanctioned, gender-based discrimination. Christina Merryman and Ameena Deramous, both former inmates in the MCIW—or the “Women’s Cut”—join Rattling the Bars, explaining the conditions faced by incarcerated women in Maryland, and what advocates inside and outside the prison walls are doing to fight for justice, in the first half of this two-part panel.

Studio Production: David Hebden

Post-Production: Cameron Granadino

Transcript

The following is a rushed transcript and may contain errors. A proofread version will be made available as soon as possible.

Mansa Musa:

Welcome to Rattling the Bars here on The Real News Network. I’m your host, Mansa Musa.

In the 19th century, women prisoners were first housed in a quarter reserved for them at the Maryland Penitentiary. They were later lodged in a section of the Maryland House of Correction, which opened in 1879. Overall, there are 854 women in the state correction system today, including women in Baltimore City Detention Center for Women, the Patuxent Institution, and intensive care treatment facilities that include male and female inmates, and the Central Home Detention unit which monitors women in their home.

The Maryland House of Correction, commonly known as the Women’s Cut, is the only institution for women in the state. This is a major problem. There’s a stark difference between how incarcerated men and women are treated in Maryland and what resources are made available to them. The procedures governing parole, security reduction, family leave, and work release are different for women in the system. I sat down to talk about the Women’s Cut with Christina Merryman and Ameena Deramous, both formerly incarcerated. Here’s part one of our conversation.

Okay. Welcome to this edition of Rattling the Bars, Ameena and Christina. Ameena, tell us a little bit about yourself.

Veronica (Ameena) Deramous:

My name is Ameena. I was just released from the Maryland Correctional Institution for Women, MCIW, in Jessup, Maryland, on January 31st.

Mansa Musa:

Welcome home.

Veronica (Ameena) Deramous:

Thank you, thank you. I have four children. I’m one of four daughters from my parents, and I was incarcerated for first-degree assault and false imprisonment. I did not know, prior to my incarceration, how broken I was or the meaning of being triggered, but once I was incarcerated I was able to, sitting down, get myself together, seek help spiritually, mentally. There were several things that could have helped me a lot quicker, but a lot of things aren’t available.

Mansa Musa:

Right. We’re going to talk about that and like I said, welcome home.

Veronica (Ameena) Deramous:

Thank you.

Mansa Musa:

[foreign language 00:02:43]. Ameena’s fasting. Today is the first day of Ramadan.

Veronica (Ameena) Deramous:

[foreign language 00:02:47].

Mansa Musa:

We’re thankful to have her here and to be able to share her experience and her stories with us. Christina, tell us a little bit about yourself.

Christina Merryman:

Hello, my name is Christina. I am a mother of two beautiful children. I am a very busy person. I work two jobs. I was released from MCIW on May 4th of this year. I came home. I got right involved with the PREPARE organization. I’m a parole advocate. I help incarcerated persons prepare for parole and go to their hearings and reenter society. I also work as an electrician. I got into the electrical trade. I am very involved with my family. I have a wonderful family, a great support network, that has stuck by my side through everything I have been through. I was away for almost six and a half years, and I got to know who I was. I got to humble myself and become a very grateful individual throughout that stay at MCIW.

Mansa Musa:

And, like I told y’all earlier, I was incarcerated in the Maryland system. I did 48. Years much like yourselves, at some point in the course of my incarceration, I had an epiphany about what I needed to do in order to maintain my sanity, because that’s one of the most important things for me at that juncture was, if I could stay sane, I could possibly survive. If I lose my sanity, I know I’m not going to survive. I commend both of y’all.

And this being International Women’s Month, I wanted to get in this space primarily to educate our audience on the prison industrial complex. We talk about it and how massive it is, but I wanted to really get into the impact that it has on women. And Angela Davis and them, they wrote a book called They Come in the Morning, they come for us at night, but in that book, it was a lot of the authors, the writers of the articles, was women and most of the women was locked up during that time, but they was locked up for their political views and that’s why they put this document out.

But when we look at the Women’s Cut, and I call it the Women’s Cut’s, it’s commonly referred to as the Women’s Cut, and it’s because of the Men’s Cut, which is now … they demolished it because of the debaucherie and the humanity that was going on in it. Ultimately, it came to a point where they just leveled it to the ground. But when you think of the Men’s Cut and some of the things that went on in there, I remember, back in the ’70s, networking with some of the sisters in the Women’s Cut when we was doing some organizing around trying to get certain things changed, and it was some real aggressive sisters. Some them was Moorish Americans, some them was Muslim, some them was just advocates that was trying to get some things done to change the way the conditions were down there.

And you said, Ameena, that you just got out. How much time did you do prior to getting out?

Veronica (Ameena) Deramous:

14 years.

Mansa Musa:

All right, so you did 14 years. When you went into the Women’s Cut, you was classified as maximum security initially?

Veronica (Ameena) Deramous:

I was.

Mansa Musa:

All right. And, during the course of your incarceration in there, did your security level ever drop?

Veronica (Ameena) Deramous:

It dropped down to medium, and when I went up for parole, I got an immediate release. It never had the opportunity to drop down any further than that and I never had the opportunity to have access to pre-release groups or classes that would’ve prepared me for my releases.

Mansa Musa:

And the tragedy in that is, I was telling Christina off mic, when we go … the men’s system … and by no stretch of the imagination do I claim to be a model prisoner. Matter of fact, I was a real live irritant to the system, and I had multiple situations. I’ve been in every jail, super-max. That’s let you know my background. But I went from max to medium, then back to max, because my behavior, from max to medium again, back to max, then to super-max. But, in each case, I had available to me, and men have available to them, the ability to go from max, medium, minimum and pre-release. In each one of these situations they’re given, they’re put in another institution, they’re given more privileges, and they’re given the ability to acclimate themselves back into society.

How does that play out with the women, Christina?

Christina Merryman:

MCIW keeps everyone housed together. I did have the ability to drop my security levels. I entered at maximum, I reduced to medium, I reduced to minimum, I reduced to pre-release, and then I reduced to work-release. I actually left the facility every day, went to an outside facility to work, and was transported back to the facility. And I had to pay rent, I had to pay fees, I had to pay room and board, transportation fees out of my check to the institution. I believe it was 25% of my overall pay that they took out of my check for me to live at the institution.

However, I was still housed with everyone, of all security levels. They do not offer a separate housing facility for any of the inmates that are, or I’m sorry, incarcerated persons, they are now referred as, for any of the different security levels. They did, right before I left, put a pre-release housing level unit as a separate section within the facility, but still housed people of all levels on that housing unit

Mansa Musa:

Okay. Now, in terms of that right there, so everybody’s in the same environment at the same time. How do they determine what you get in comparison to what other security levels get? Like I said, if I’m in a man’s facility … I left from JCI, I left from right down in that region, and they had medium, minimum, they had minimum, then they had work-release, and the men in work-release was going out working at Golden Corral and all these different places and coming back, and they was getting family leave. I just didn’t get that because I had a mandatory out, which is I made my mandatory as far as my parole. That’s the only reason why. But in terms of … did y’all get family leave?

Christina Merryman:

No.

Veronica (Ameena) Deramous:

Absolutely not.

Christina Merryman:

Denied.

Mansa Musa:

Did y’all-

Christina Merryman:

All requests denied.

Mansa Musa:

In terms of work release?

Christina Merryman:

Denied, all requests denied, for any special privileges, any special requests, any special anything, denied

Mansa Musa:

And what was the reason, in any case?

Christina Merryman:

The biggest reason they always referred to towards the end of my stay was COVID. Even though COVID was over with for two years, it was still COVID. That was their biggest go-to, any request that I ever made for the family leave, because I always brought it up when I was on work-release with the COMAR codes and everything was, “I’m entitled to this, I’m entitled to that.” No, COVID, denied.

Mansa Musa:

And when you refer to COMAR, that’s Code of Maryland Regulations and that’s the regulatory. They regulate the policies and procedures around the state of Maryland and different agencies, the Department of Public Safety and Corrections is one of the many. And then the Department of Public Safety and Correction, when they do a COMAR, COMAR has parole regulations in there. COMAR has work-release regulations in there. COMAR have family leave regulations in there. COMAR have pre-release regulations in there. COMAR even have the ability where you can go out, as we was talking, in the Maryland system, you don’t have to go to work-release, you can go to school, you can ask, “I want to go to Coppin State College, I’m pre-release, I want go to Coppin State College and come back.” And according to the Maryland regulations, this ability exist. Did y’all see that?

Veronica (Ameena) Deramous:

I had just left in January. Those rules don’t exist. They exist on paper only. They don’t exist. They’re not being applied, and it’s really, really hard to fight them. The three jobs that the women are allowed to have at MCIW is Panera Bread, Hardee’s, and the Maryland correctional Enterprises. We are being told that we can’t work anywhere where there are men. The ladies that are in the work-release program, they’re double-bunked, and they’re paying over $700 a month and they’re double-bunked. We have what looks like a pre-release unit, but it’s just another housing unit. Those ladies will never be able to have pre-release opportunities inside of a correctional facility. It’s not possible. We’re all there together. When you were on work-release, I was there, and I wasn’t pre-release or minimum. I was either medium or maximum, but I saw you.

Christina Merryman:

Yep. Every day.

Veronica (Ameena) Deramous:

Right? Things existed in writing, on paper, but not in reality.

Mansa Musa:

And I recall … because we did this, we interviewed a sister that was advocating for, in the Women’s Cut, and trying to get some policies, more importantly, trying to get the State Assembly and the governor to build separate facilities for women or create a mechanism where they can get out and have access to the same things that men … and it became apparent that, for whatever reason, y’all not relevant, and for whatever reason. Why do you think that? Why do you think that the men … and mind you now, I told you, I’ve been to all the institutions, it’s not no cakewalk on that side.

Veronica (Ameena) Deramous:

It’s not.

Mansa Musa:

It’s not no cakewalk with men, but in terms of the availability, why you think that y’all being … and this is what I want the audience to understand, we talking about the same rules and regulations. If I get caught with money in prison or a knife in prison, they going to find a rule, contraband category one, lock me on behind the door.

You get caught with a knife, money, in a prison, category one, you going behind the door. I go up for parole, they can say, “Okay, go get the work-release before you come back up.” I can come back up for parole, and this is what I want the audience to understand, I can come back up for parole and be in a work-release environment, be working in Golden Corral, been working there for the last six months, and when I go back up for parole, say, “This is where I’ve been at.” They can tell you the same thing, say, no, they ain’t going to tell you that, because they tell you that mean that they got to have you do something that the institution’s saying I do. Isn’t that a problem in terms of parole?

Christina Merryman:

Yes, because parole puts stipulations and regulations that they want the incarcerated person to accomplish. MCIW makes it virtually impossible for us to accomplish those things. First off, you can’t get into classes when you’re not on a certain level. The administration chooses who they want to choose and place in those classes. There is no proper procedure. The people in the administration, and the certain officers that handle the way they choose the incarcerated persons to participate, have their favorites. Honestly, it’s like you are in a high school all over again. There is no proper structure, there is no proper help, and you can’t go to a certain officer to have help because, when you do, it gets back to the entire population. It’s horrible.

Mansa Musa:

And you say you did 13 or 14 of your …

Veronica (Ameena) Deramous:

Yes.

Mansa Musa:

How much time did you have? What was your overall sentence?

Veronica (Ameena) Deramous:

I had life suspend all but 25.

Mansa Musa:

Right. You did did 15-

Veronica (Ameena) Deramous:

14-

Mansa Musa:

14-

Veronica (Ameena) Deramous:

… off of my life suspend-

Mansa Musa:

So you mandatoried out?

Veronica (Ameena) Deramous:

No, I didn’t mandatory out, but I definitely did-

Mansa Musa:

You went out with days?

Veronica (Ameena) Deramous:

Yeah.

Mansa Musa:

You made parole with days?

Veronica (Ameena) Deramous:

Well, I just made parole. I was granted parole, and if I had not made parole I would still be there because of the system. Let me reiterate some of the things-

Mansa Musa:

Come on.

Veronica (Ameena) Deramous:

… that she said. Again, we have a list of groups and classes and programs on paper, but we don’t have those groups and programs active.

Christina Merryman:

True.

Veronica (Ameena) Deramous:

We have groups and classes and programs that you can be certified in and you can take those classes if they pick you. And, once you’re done with that class, the testing part isn’t there.

You have a certification class that’s being given without the certification. Then do you have a certification class?

Mansa Musa:

No, you just do a class.

Veronica (Ameena) Deramous:

Okay. And we may have three or four of them, and then we lose the instructors, and so then we don’t have those. Hospitality, certification class, I was in that class when the instructor left for whatever reason and didn’t finish it. They said they were going to do cosmetology, but they did a barbering course in the women’s prison. And the ladies have taken … before I left, they were on their second group going through, and the first group, they still hadn’t figured out how they were going to test. The staff, I was in the military, I was in the United States Army, I never would have imagined going into a state facility not having any discipline or structure at all. The officer in the building, the officer on the grounds, every time there’s a different officer, there’s a different set of rules.

Mansa Musa:

There’s a different set of rules, that’s right.

Veronica (Ameena) Deramous:

Coming from the military, there’s one set of rules and everyone follows that set of rules.

Mansa Musa:

Yeah. Ain’t no consistency, ain’t no consistency.

Veronica (Ameena) Deramous:

None. And then, if you take officers who have no rank at all and put them in positions of power, you take an officer and make that officer the VAC coordinator who’s over all the programming, if she doesn’t like you, you won’t be-

Christina Merryman:

You don’t [inaudible 00:19:41].

Veronica (Ameena) Deramous:

… participating in those classes.

Mansa Musa:

Your volunteer activity coordinator.

Veronica (Ameena) Deramous:

Correct. You take another officer and you make them a case manager, and they don’t like you, but your case managers play a very large part in you being incarcerated. You take another staff member, off the ground, and make them the ARP coordinator. That’s a big problem.

Mansa Musa:

Yeah, yeah, administrative procedure.

Veronica (Ameena) Deramous:

Ho I going to complain about you, or any of your friends, and you’re handling the paperwork?

Mansa Musa:

And you know what? And, as you outline that for the benefit of our audience, this is important that we understand that what we’re talking about here is equity and equality, because we’re not complaining about, okay, you have this narrative crime, crying, time, if you did the crime, do the time and stop crying, but this ain’t about none of that. This is about, if the Code of Maryland Regulation says … it doesn’t say, “This is what the Code of Maryland Regulation say.” Code of Maryland Regulation don’t say, “In women’s prison, women get three meals. In the men’s prison, men get four meals.” It don’t say, in the Code of Maryland Regulation, say, “In women’s prison, women get one hour of rec and men get all-day rec.” It’s a uniformity, to go back to your point, it’s a uniformity from Department of Public Safety and Corrections all the way down.

It’s a uniformity, but it’s only a uniformity when it comes to men’s prison. And so I want y’all to flush out this as we go forward. I want y’all flush this idea out, what impact does that have on your ability to maintain your sanity and get out? Because both of y’all got out. I’m not going to claim that I wasn’t damaged. First thing I got, when I got out, was mental health, because I understood that I needed to understand a lot that was going on, and I got good support in that work. But I understood this here that wasn’t nobody did four and a half years in that super-max. I did that on that, [inaudible 00:22:01] part around 12 people, and I knew it impacted me. I knew I had to get some type of help.

Let’s start with you, Christina, how did that impact you in terms of your ability to function and survive to the point where you was able to get out?

Christina Merryman:

I am a people person. I am a social butterfly. I was all over that compound. I love people. But I found myself, when I was away, I isolated a lot, because the surroundings around me, mostly officers, if I didn’t, they will try to pull you out of your character to see you fail, and knowing that I had to isolate more of who I was and shut down. Coming home, it was a little bit of a struggle because … first thing I did was mental health. I see a therapist. I’ve never done that before in my life, and my mom doesn’t understand it. She’s like, “You don’t need that.” I’m like, “But I do,” because it’s such a change now that I’m home and I’m able to be this social butterfly again and not have that worry of who’s there, is somebody there, that person in that black uniform going to try to get me out of my character? It is a little bit of a struggle, when I first came home, of being able to be my true self and not have that tension, and it shouldn’t be that way.

Mansa Musa:

No. And I’ve been in that space. I was in Islam. I did a whole murder, different thing, and I recognized that we had to, in order to get food during the Ramadan, in order to get the opportunity to fast and be able to break fast, it was a whole lot going with that. Matter of fact, Salaam versus Collins, a case that came out, Salaam versus Collins, where the Muslims sued to get a Islamic coordinator in the environment.

Black woman, Muslim and incarcerated, and like you say, I got your military background, so you got a certain discipline, but how was you able to maintain in being in that … and you also said, off camera, that you was a litigant, you was litigious, so you was a [inaudible 00:24:56] for the powers that be, which was a good thing. How was you able to maintain and be able to get out without finding yourself with an adjustment record that supersedes the amount of years you done?

Veronica (Ameena) Deramous:

Retaliation is real, believe that. I got one ticket, I got caught with a cellphone, because I was an advocate. So many things happened there that I tried to write up that could never get anywhere, that when they were passing a cellphone around, I got it. And when I had it, I was taking pictures of the maggots in the shower. I was taking pictures of all the goose poop that’s on the ground that we, as incarcerated individuals now, we know that outside people are coming because the grounds smell grapey. They have something to get rid of them when the time is necessary. Even if you do complain about something, before someone can come in, they will have fixed that, in addition to they’re not going to take you to the place exactly that we were speaking of. The staff members, some of the staff members, they clique up like the residents clique up. A couple of times, we were trying to figure out if they were members of specific groups.

Mansa Musa:

I understand.

Veronica (Ameena) Deramous:

When you’re trying to get better, when you’re trying to do better, but you’re being agitated, it’s hard. I’m not saying … and please, I don’t want you to think for two seconds that I feel like I did the right thing or that I didn’t deserve to do time, but I didn’t deserve to do time like that.

Christina Merryman:

Yeah, I agree.

Veronica (Ameena) Deramous:

I didn’t deserve that. I’m not exactly sure how things go, but I almost felt like MCIW had some type of protective shield because we couldn’t get the word out. My mail didn’t go out. My mail didn’t go out. I would get my mail back two months later, opened. You can’t get the information out. Even to hear you say that you complain about things and you’re able to make a change, we weren’t, are not, able to make those changes because we can’t get to anyone.

Mansa Musa:

Let me ask you this here. Going forward, what do you want to tell the women that are back … they’re still in the Women’s Cut. What do y’all want to tell them as we wrap this segment up about what it is y’all want them to leave them with in terms of motivating them in the spirit and get them to maintain? Christina?

Christina Merryman:

To try to do what I did, get involved in everything you can possibly get involved in. Stay busy. Stay connected with as many outside connections, support members, that you have. Stay positive. Keep a smile on your face, and kill every officer with as much kindness of spirit as you have. And do not, no matter what, let them rent the space in your head to take you out of your character, because they’re not worth it, and it will get better because there’s a date, you will have your date, your time will come, and it will get better. And you’ve got girls like us. You’ve got your advocates.

Veronica (Ameena) Deramous:

Absolutely. For me, I want everybody to know that I love you guys.

Christina Merryman:

Yes.

Veronica (Ameena) Deramous:

I was excited and sad to leave at the same time. I left my family, my children, my parents, my sisters, for 14 years. But when I left MCIW, I left a different family. I had a lot of support and I’m grateful for that. I want you ladies to know that there are a group of us that have been released and we are fighting on your behalf and we’re going to get the word out. They let out the right ones. [foreign language 00:29:41].

Mansa Musa:

That’s right, that’s right.

Veronica (Ameena) Deramous:

They let out the right group of ladies. We got you.

Mansa Musa:

Yeah. Okay. We Rattling the Bars. We got Ameena and Christina, recently released from the Women’s Cut, as we refer to it, and as we recognize from this conversation that it is in fact a notorious environment. But, like the phoenix, both of these young ladies, both of these ladies, has risen, and we are here to advocate on behalf of our sisters. We don’t leave nobody behind. There you have it. The Real News, Rattling the Bars.

Speaker 4:

Thank you so much for watching The Real News Network, where we lift up the voices, stories, and struggles that you care about most, and we need your help to keep doing this work. Please tap your screen now, subscribe, and donate to The Real News Network. Solidarity Forever.